Charles Paccione

Oslo, Norway

|

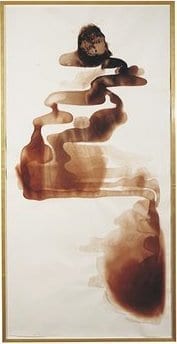

| Goldsworthy, Andy. Born 1956. Watercolour. Great Britain in 1991-1992. In storage, museum no.: E. 705-1993 |

Throughout my years of working with patients, both as a therapist and as a clinical researcher, I have been consistently reminded of the important role storytelling plays in fortifying a healing bond between patient and caregiver. Listening to patient stories of illness remission and recurrence, of risky treatments and procedures, and of uncertainty for the future provides me with the landscape of their illness as it is experienced. By sharing an illness narrative, a patient can regain a deep sense of intimacy and relationality with their illness that may have been objectified through months or even years of clinical treatment and psychophysiological alienation. This can give a caregiver a new and intimate understanding of how a patient is experiencing their illness in mind, body, heart, and spirit. On a recent trip to Paris, France, I was reminded of how the act of listening and attending to another’s illness narrative is a treatment of its own.

Upon arriving in Paris, I dropped my bag off at the hotel and immediately went out onto the city streets, eager to taste this “moveable feast” that Hemingway wrote so eloquently of. I made my way up Rue de Bourgogne, following the beautiful succession of old wooden doors that lined the cobblestone sidewalk, and eventually came across a huge dark-blue door with Musée Rodin carved above it. I took a moment of silent reflection and then decided to enter and explore what awaited me on the other side. There, sitting on a rock and bent over with hand under chin in eternal contemplation, was Auguste Rodin’s bronze sculpture Le Penseur.

I took my time walking slowly around the bronze thinker, looking upon his back and the articulated muscles of his arms. His deep-blank eyes stared down at pink roses that grew near my feet in the surrounding garden. I realized that there was a deep silence inherent in the statue that was charged with contemplation, reflection, and cognition. This man was thinking so deeply about something that would always be beyond an answer or solution. He will always be contemplating that which is beyond knowing and grasping. I closed my eyes and began to remember the many moments I too felt immersed in a deep and silent contemplation while listening to the unknowable and unanswerable narratives of my patients.

Every week I lead a contemplative therapy group for cancer patients suffering from depression, anxiety, and stress at a clinic in the Bronx. One day, Sarah, a cancer patient whom I saw often, began to tell her illness narrative by giving voice to the layers of meaning, circumstance, and events that surrounded her cancer. She began this narrative with a recognition of the losses she has experienced:

After working with a company for 35 years I was let go. And in January of 2010, the following year, I lost my mother. And in August 2012, I was diagnosed with lung cancer. . . even though I never smoked, never drank and lived a clean life. And then in 2013, my husband served me with divorce . . . They told me it’s not operable and it’s not curable so I have to try and live with it; I have to live with this down in the valley . . . I went to work diligently. I would say a model employee, I couldn’t understand why they fired me, but we figured it out afterwards. So you have four catastrophic things happening to one person . . . So why is all this happening to me?

Sarah’s question is often seen by mental healthcare professionals as a heroic chance to give the right answer, an answer that would make Sarah feel content as to the reason why she lost her mother, was diagnosed with lung cancer, fired from her job, and divorced by her husband. But I chose to hear this as an invitation to breathe with uncertainty, to be in the unknowing with Sarah, and to sit with the question—to allow it to open into the room and have space among the others sitting there before her. By sitting with the questions and allowing the uncertainty of the narrative to have its space within the room, Sarah, and many like her, can begin to feel that they are not alone in recognizing a life of challenges and losses. By giving her question an answer, or even a follow up question of my own, I would have changed the natural progression of Sarah’s narrative. That morning I chose to take on the position of Le Penseur in order to listen, witness, and contemplate what will forever be beyond the realm of knowing. After touring more of the surrounding gardens I left the Musée Rodin and headed across the Seine for lunch at the home of my good friend, Jean-Christophe.

Jean-Christophe and I have been friends for many years and became especially close when his father, Gabriel, was diagnosed with lung cancer and I was asked to see him weekly for therapy. Every week I would go to see Gabriel and guide him through various meditative stress reduction and breathing techniques in order to modulate his parasympathetic tone, fortify his psycho-emotional well-being, and to witness, listen, and engage with the stories of pain, loss, and uncertainty. My private visitations continued until Gabriel finally passed away from his cancer. I had not seen Jean-Christophe for a long time since his father’s passing so my visit to his home that evening in Paris was quite special—it was a time to reflect, remember, and discuss what the future held.

Jean-Christophe greeted me warmly with a tour of his home that was filled with exquisite pieces of contemporary art, many of which were previously owned by his father. As I walked through Jean-Christophe’s home I recognized many of the artworks that used to hang in Gabriel’s living room where we had our private therapy sessions. But not until I saw a work by Andy Goldsworthy, a British contemporary artist, hanging on one of the walls, was I struck by a memory of listening to Gabriel breathing during our last session together.

After many surgeries and chemotherapy, Gabriel had lost much of the lower portion of his lungs. This caused his breathing to be shallow, weak, and raspy. He suffered from insomnia and felt anxious and out of breath throughout most of the day. On our last session, Gabriel was lying on his back upon a soft white mat on the floor. I remember looking at his upper chest that was trying to pull in as much air as it could, but never enough. I placed my right hand on his chest and my left hand on his stomach and instructed him to try to move my left hand as he breathed while relaxing his upper chest. Gabriel closed his eyes and began to breathe deeply into his stomach but started to cough and shake. I wanted to breathe for him and expand his lungs somehow, but I knew that I could not. I could only listen. And as I listened, I looked up and saw the painting by Andy Goldsworthy.

In order to create the painting, Goldsworthy made a snowball that incorporated crushed red stone from the source of Scaur Water, a river in Scotland, and placed it on the top edge of a large tilted canvas. As the snow melted, the dark red pigments from the stone slowly spread down the paper, staining the paper like a watercolor wash. But one of the most fascinating aspects of this work is how Goldsworthy chose to simply sit back and witness the work coming into being:

“I can control the rate of melt to some extent because of the heat of the room, but I would never start tilting the paper. For the drawing to have its integrity, and strength of an artist, I have to kind of stand back; and that’s a really interesting situation for an artist to be in, where actually not making something produces a far stronger result.”1

Even though I wanted Gabriel to breathe deeply, slowly, and calmly, I could not breathe for him. The only thing I could do was to sit back, witness, listen, and hold a safe space for him to take part in the processes of the struggle. I needed to recognize his desire to establish integrity and stability with his illness and his body.

After a while I finally walked away from the painting and joined Jean-Christophe for dinner. But later that evening, as I tried to fall asleep, I thought about listening to Sarah’s questions without answers and engaging with Gabriel’s process of struggle. Witnessing, listening, and engaging an illness narrative concerns me most in medicine. Each of these three practices takes the will to contemplate something that is beyond our medical knowledge, hear the voice of a woman not heard, and feel the struggle of a man trying to take another breath.

Reference

- “Andy Goldsworthy – ‘We Share a Connection with Stone’.” TateShots, Tate, 1 Dec. 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9DjCMqtJr0Q.

CHARLES ETHAN PACCIONE is a PhD candidate in Medicine and Health Sciences at the Department of Pain Management and Research at Oslo University Hospital in Oslo, Norway. He holds his M.S. in Narrative Medicine from Columbia University’s School of Professional Studies and his M.A. in Psychology in Education from the Spirituality Mind-Body Institute, Teachers College, Columbia University. He is currently developing innovative psychophysiological treatments for patients suffering from chronic pain.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply