Dhastagir Sheriff

Chennai, Tennessee, India

|

|

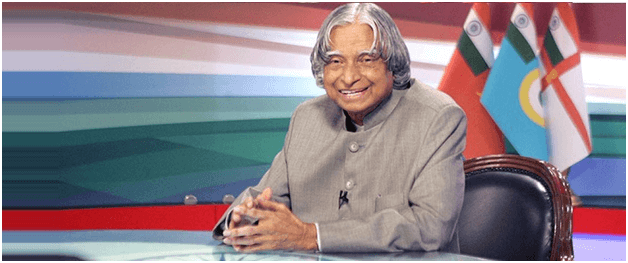

Late President of India Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam |

I was working as a professor of biochemistry and as the vice-principal of faculty at the Ambedkar Medical College in Bangalore. It was a welcome change after working in Libya for ten years and I was bubbling with energy and ambition to serve the cause of education. I felt that a professor could yield a vast influence on his students and set the right temperament for their arduous years of study. Acting as a father figure for the first-year medical students created a bond based on trust, honesty, and discipline. The students I taught came from all the states of India and had a cosmopolitan outlook.

They visited my house every weekend and stayed with my family on Saturdays and Sundays. I knew the concerns and needs of every one of the students’ families. They in turn knew that I had an ailing eighty-year-old father with a handicap. He had a cardiac condition and had fractured his hip. He had opted for hemiarthroplasty instead of a joint replacement, so he walked with a limp and had difficulties carrying out his daily routine.

My father was also my mentor, a philosopher, and a unique person. His family life is an example of how one could adapt and live according to the life one adopts. Marriage in Islam is a contract. The priest visits the bridegroom and bride and takes individual consent, which gives the woman freedom to accept or reject the marriage. But after his first night of marriage my father found that his wife was schizophrenic and did not know how to take care of herself.

|

| My mother at the time of her marriage |

My mother wore torn clothes, slept on an old mattress, and smoked cigar butts. She lived in her own world. My father, after finding out about her condition, decided to continue to live with her because he had promised the priest that he would marry her. She gave birth to me and to a daughter who died young. My father prepared the food for both his wife and son for some forty years. He lived that life happily and took pleasure in taking care of us. He planned everything and was a strict disciplinarian. When offered perks and extra money he would flatly refuse such contributions. He had a regular income from his government service as a commercial tax officer. His routine diet was a bowl of rice, gravy made out of dal or mutton, and yogurt. He took a cup of tea at night and give a glass of lemon juice to his wife and son. Every day before going to bed he ate an orange. He did not smoke or drink. He did not have a two- or four-wheeler. Once he got a motorcycle and fell down driving it. He sold the vehicle immediately, stating that he needed to be more careful as he had to take care of his wife and son. After he fractured his hip, this independent man became slightly dependent on a walking stick to walk and carry out his daily chores with restricted mobility. What kept his life going was his schizophrenic wife.

During one of my summer vacations from Libya I saw my mother staying in Chennai and my father at Salem, as he was not able to strain himself. My mother refused to go along with him to Salem because she felt secure in the place she had been living for so long. When I visited my father at Salem I received a phone call that she had been admitted with severe diarrhea and would not recover from it. I had to order an ambulance to take her to Salem. On the way she passed away in my lap. My father said that she was lucky to die in the presence of her only son and husband.

|

| My father sleeping on a cot and the special pair of chappal he wore after his fracture |

A few years later my father called me saying he was feeling lonely and wanted me to return to India. So I left Libya and started working in Bangalore. When my father was hospitalized, I was called to his bedside. His vital signs were failing and it was recommended that he undergo a thoracotomy. He instead requested to be allowed to die in peace without the procedure, for in Islam one wants to die with no scars or wounds. He died the next morning.

The first-year students from Ambedkar Medical College came to know about the death of my father. They all took a bus from Banglore to attend my father’s funeral. When my father’s body had to be washed before being clothed (the kaffan of a male should consist of three white winding sheets), four Muslim students washed his body and covered him with white cloth. He had requested to be buried alongside his wife’s grave. I went to the graveyard to pay for the place of burial and was shocked when the undertaker told me that my father had visited him a month ago, paid money for the place, and informed him that he would die on such a date and time. The undertaker had already dug his grave and was ready for my father’s burial on that exact date and time.

Primo Levi said, “There are few men who know how to go to their deaths with dignity, and often they are not those whom one would expect.” Death and the fear of facing death are a concern for everyone. If a person was told that he would die soon because of a terminal illness, that fear could become a nightmare. But to await death with dignity as my father did, to fix a date and time to die, and then to die on that very date and time, is something very few people could comprehend or accomplish.

DHASTAGIR SULTAN SHERIFF, PhD, is a retired professor from the faculty of medicine at Benghazi University in Libya. He is now living in India and has an expertise in medical biochemistry. He is the author of a text book titled Medical Biochemistry along with five monographs and over 150 research publications. He has written this article as his token of love and gratitude to his father.

Leave a Reply