Kelsey Hart

Denver, Colorado, United States

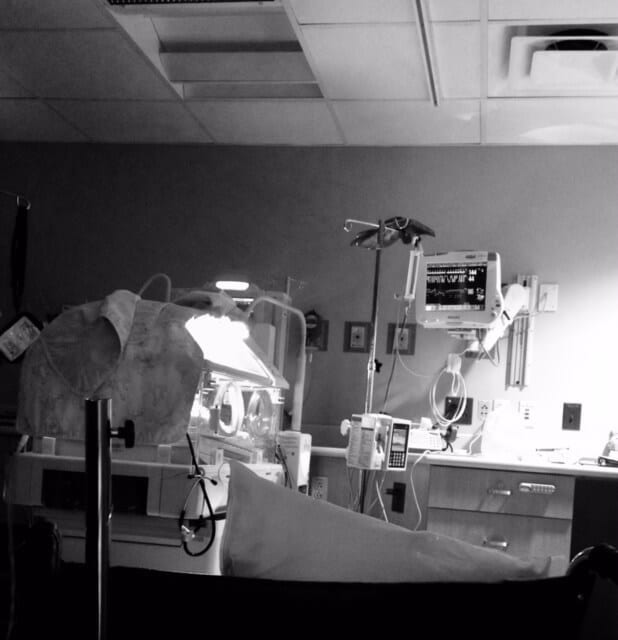

I sit in the blue plastic recliner, coping with the familiar feeling of boredom and anxiety by flicking through a game on my phone. My daughter dozes in the climate-controlled isolette in front of me. I glance up at the white board hanging on the wall. My daughter lost 20 grams last night. A quick Google search tells me that is about as much as a mouse weighs, which is saying something considering my daughter started at a mere 960 grams.

I recognize the voices in the hallway and steel myself. The neonatologists, nurse practitioner, nutritionist, and nurses are gathering for their daily rounds. Since my daughter lost weight again last night, I dread this conversation more than usual. It seems we have tried nearly everything to get her to gain weight. I have pumped breast milk, capturing the fore milk and hind milk separately. The nutritionists have fortified my breast milk, something akin to a preemie protein shake. The nurse and I have even added tiny drops of canola oil to her milk. Her neonatologist called it her “first French fry.”

I am terrified of what comes next. And yet, as the group of white coats and blue scrubs gathers in front of my daughter’s room, it is the nutritionist who suggests it first.

“I think maybe it’s time we try formula,” she proposes innocently.

My stomach turns. As the mother of a fragile premature daughter, I feel helpless. I need a nurse’s help to feed her, change her diapers, and even to hold her—to keep the delicate web of cords from tangling or becoming unplugged. This breast milk that I pump from my own body into sterile plastic containers every three hours is the one tangible thing I can give to her. I know how irrational it sounds. I read to her, I sing to her, I hold her for the allotted time—one precious hour—each day. I am convinced she knows I am here. I have convinced myself she knows I am her mother, and not one of the many nurses she had met during her short time on this earth.

All of this runs through my head as I struggle for the words to respond to the nutritionist. I want to advocate for my daughter, for our little family. I trust this team of people explicitly; I have no choice. They have the knowledge and experience and have been keeping my brave daughter alive and growing. This nutritionist is just the first in a long line of professionals who will try to do what is best for my daughter. But it is me who sits at her bedside, day in and day out, listening to the monitors beeping and the machines helping her to breathe. I am the one who will eventually take her home. It is my responsibility to balance their professional opinion with what I know to be true about my daughter and her needs. I need to find my voice; I am her mother.

I am too busy paying attention to my internal dialogue to realize that the conversation has continued without my input.

“What do you think, mom?” The neonatologist graciously interrupts my overthinking.

I am grateful. He and I have had this talk already; he knows how unexpected all of this was. How my healthy thirty-two-week pregnancy turned into a two-pound, two-ounce baby with very little warning. He knows how important breast milk is to my plan, or whatever shreds of my plan are left. The others in the team may not know how I feel, but I sense they can tell I am none too pleased by how I have tensed up and crossed my arms across my body.

“I’m not sure I’m ready to give up on breast milk quite yet. Do you think we could give her a little more time?”

I am flooded with relief. Even if they decide to go in a different direction, I have done it. Spoken my piece, found my voice. Earlier in the process, when my daughter’s condition was much more unstable, I just nodded along. I signed the forms and tried to keep up as best I could with all the tests. The world is dim, hushed, and rushed in the NICU’s suspended time. At times, it feels like our stint here could go on indefinitely. I do my best to be present to the tiny daughter in front of me, as there is never a guarantee of any more time. But in that moment, with her team, I gave myself permission to glimpse our future. Before I settle back into that blue plastic recliner, I stop to open the portal and reach into the isolette. I place my pinky into my daughter’s hand, as the nurses have instructed, and feel her fingers squeeze tightly.

KELSEY HART, MAPSC, has spent nearly a decade working in nonprofit and church settings to care for individuals and families in crisis. She is currently writing a memoir and is mother to one young daughter.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 4– Fall 2018

Leave a Reply