Susan Kaplan

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

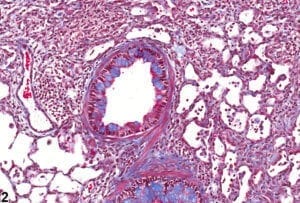

| Lung, Bronchiole – Metaplasia, Goblet cell from a male Sprague – Dawley rat in an acute study. National Institutes of Health. |

I hear a cough in the dark. Like all mothers, I am exquisitely attuned to any sound from my children in the middle of the night. A few more coughs. Silence. More coughing. I get out of bed and go into Benji’s room to check on him. The cough has not awakened him, so I get back into bed and close my eyes. But then it starts again, louder, more insistent, as if reverberating off the walls. He is now awake and upset. I hear a kind of hiccup when he inhales that I instinctively know is wheezing. “Are you having trouble breathing?” I ask. He nods.

Benji is growing up a mile from where I grew up. As a child, I did not know anyone with asthma. When I took ballet lessons in fourth grade, there was not an inhaler to be seen—I had never seen one and would not know what it was if I did. Later, I had a friend in law school who was the first person with asthma I ever met.

Records of people suffering from asthma go back centuries. French novelist and essayist Marcel Proust wrote long letters to family and friends about his asthma symptoms and the many ways in which he tried to relieve them. But it is now an international epidemic. At Benji’s school, it is practically normal. When his fourth-grade class had a strenuous running exercise in gym, the teacher told the kids, “Bring your inhalers.” When Benji took a break-dancing class in fourth grade, the inhalers were lined up next to each other on the windowsill just like the kids in the dance studio.

As an environmental and occupational health lawyer and researcher, asthma had long been at least in the background of my work, but mostly at a scholarly distance. Once my older son was diagnosed with asthma, however, I was forced to learn about its causes and triggers. On Benji’s doctor’s recommendation, I vacuumed often with a HEPA vacuum cleaner, zipped dust covers onto his mattress and pillows, and placed an air filter in his room.

Beyond allergens like dust mites, animal dander, and grass pollen, however, I found I was largely on my own when it came to protecting Benji from environmental triggers. I ended up talking with child care and school teachers, principals, custodians, and facilities directors about air fresheners and bleach cleaners, and to the school bus company about idling. Many of these issues were, fortunately, addressed by policies I was slowly learning about. I looked for summer activities that would not involve Benji being outside all day, given the preponderance of orange and red (high air pollution) days during the summer in Chicago, where we live.

Far more challenging, I tried to persuade a nursing home that was directly across the street from our local elementary school to stop spraying its expansive lawn with herbicides, which become airborne and are linked in many studies with asthma problems. After applications, I could smell the chemicals for weeks. I wrote a letter to the home’s executive director and medical director, co-signed by a few neighbors. The executive director wrote back that having an attractive lawn was important to the residents and that the chemicals were legally applied. True—but it can be difficult to explain that many (well, tens of thousands of) chemicals in use have never been adequately tested for safety, not to mention for their synergistic effects and for their particular impact on sensitive populations like young children.

I asked local officials for assistance, to little effect. In retrospect, I did not push hard enough. In my insecurity, I reached out nervously, then pulled back. I think that as a woman, I felt particularly uncomfortable being assertive. Women tend to apologize—sorry for bothering you, sorry for taking your time—and while I knew I was right, I fell into that pattern. I requested a meeting with my local representative by email, then by phone, but he did not respond. I should have called regularly until he did.

On a fellow advocate’s advice, I created a website full of information about the hazards of the chemicals, as well as safer alternatives, linked it to an online petition, then sent an email to neighbors and friends. With the website and petition live, I felt so anxious that I was afraid to look to see who had signed. (Sorry for bothering you! Sorry for taking your time!) Yet nervousness gave way to relief as a few signers turned into dozens, and fellow moms I ran into said unexpected, nice things. The PTA president was supportive. Another mom said the website worked because it was full of information and direct, unemotional.

The spraying stopped—for a while. But institutional memory can be short, and the nursing home never truly understood the issue, so there was not the kind of culture shift that leads to genuine, lasting change.

Four years after Benji’s asthma diagnosis, I still spend dozens of hours every year advocating for his environmental health. It still is not easy and it still makes me nervous, but I have developed more confidence and more of an activist’s toolkit, including working to develop coalitions rather than trying to achieve change all by myself.

I recently met a neighbor who does the same kind of work and shares my concerns about asthma triggers in our neighborhood, as well as knowledge about policy and practice changes that could make them better. It is still a long way from a real movement for improved children’s environmental health and asthma conditions. But there is the beginning of a path forward.

And a path was identified by the physicians who are on the front lines of these issues: pediatricians. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued a powerful policy statement a few years ago that, although it focuses on pesticides, could apply to children’s environmental health in general, or even community health overall. Pediatricians “should ask parents about pesticide use around the home and yard” and recommend lowest-harm approaches, says the academy. “Pediatricians should also work with schools and government agencies to advocate for the least toxic methods of pest control, and to inform communities when pesticides are being used in the area.”

This vision of doctors emerging from their offices to work with communities feels simultaneously revolutionary and common-sensical. After all, asthma, like many diseases, has more than one cause—many of which are environmental—and more than one solution, many of which are found outside the physician’s examination room.

It may be true that, as Jerry Seinfeld said, lawyers are the only ones who have read the inside of the cereal box; in other words, we know what the rules (laws, policies) are. But doctors should be the natural allies of lawyers and policymakers. The vision of the AAP statement may be mostly a pipe dream at present, but it is my dream.

“Are you having trouble breathing?” It is a question no mother ever wants to ask her child.

References

- “AAP Makes Recommendations to Reduce Children’s Exposure to Pesticides,” American Academy of Pediatrics, November 26, 2012, https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/pages/AAP-Makes-Recommendations-to-Reduce-Childrens-Exposure-to-Pesticides.aspx.

SUSAN KAPLAN is an environmental and occupational health attorney, researcher, and writer who has worked in federal and state government and in academia. Her articles, opinion pieces, and essays have been published in the Washington Post, Boston Globe, Christian Science Monitor, and Chicago Tribune, among others.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply