Marlene Berman

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

|

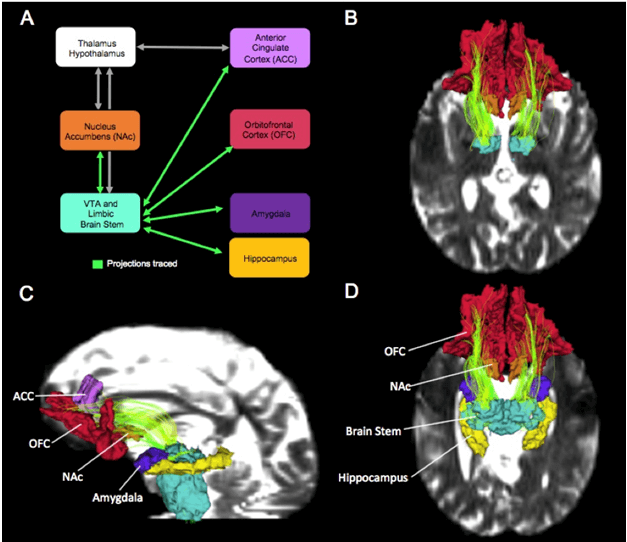

| The Extended Reward and Oversight System (EROS). Image A shows the major brain regions in EROS. Images B, C, and D show different views of a main fiber tract, the medial forebrain bundle (chartreuse), connecting the regions in EROS.7,9 |

Neuroscience is demonstrating that torment can be eliminated by altering one’s memories of the original circumstances responsible for the anguish. The changes occur when the old memories are retrieved, reappraised, and reconsolidated differently.1,2

Retrieving, Reappraising,

and Reconsolidating Memories

Our brain allows us to learn and then to recall events, feelings, perceptions, and actions. In so doing, engrams (memory traces) are formed in the brain’s neurons. Over time, through a progression of review and reappraisal, memory traces can be updated (biochemically and structurally) and then restored in the brain as slightly different, often stronger, memories. This is called reconsolidation. However, if the natural process of reappraising and reconsolidating the reactivated memory traces is interrupted or destabilized, the typical progression can be impeded, or stopped. The best way to destabilize memories before they are reconsolidated is to confront them with unexpected conflicting events or feelings – whether positive or negative – at the time of recall.2 In clinical settings, new emotional experiences can be integrated into memories as they are being reconsolidated, and depending upon the nature of the problem, various therapeutic approaches have been successful in treating emotional disorders.1,2 A simple example is the elimination of someone’s fear of spiders by having the person gradually approach tarantulas, followed each time by administering a pharmacological agent that alters reactivated memory traces of spiders. Here, the change, i.e., diminished fear, is reconsolidated into the original engram.

In clinical settings and in experimental research, reactivated painful memories include dreaded objects (e.g., spiders or snakes) or specific events (e.g., combat or rape). However, individuals suffering from prolonged psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, obsessions, or dissociation, might not be able to connect their overwhelming negative feelings with conscious memories of fearful objects or events. Instead, over time the pathology becomes diffuse and difficult to define.

We describe a psychodynamic treatment in which reconsolidation occurred through the relationship between a patient (Ms. Z) and her doctor (Dr. A). The case is presented from both clinical and neuroscientific perspectives. It chronicles the patient’s transformation from suffering, to deep, lasting change of mind and brain, by retrieving painful memories, reconsolidating them under therapeutic conditions, and integrating positive emotional experiences. The intervening agent was the therapist in a milieu of sustained trust. Such treatments were the foundation of psychotherapy during the last century when psychoanalytic theory offered the best Theory of Mind. In this century, even as neuroscience explores reconsolidation with controlled experimental paradigms, truly transformative therapeutic relationships are rare and unusual.3

Clinical Observations

Ms. Z was a young professional woman who experienced severe anxieties and extremes of mood. Feeling lost and contemplating suicide, she sought treatment at a hospital clinic. Ms. Z was referred to Dr. A, a female psychiatric resident, beginning what was to become a decades-long psychoanalytic journey of exploring the intersection of mind, brain, and psyche. Through this sustained relationship, Ms. Z eventually was able to recall, reassess, and reconsolidate emotional experiences at both autonomic and conceptual levels. The eventual changes were profound, and happened in ways unanticipated by both parties.

A series of countless repetitions of early emotional memories began to unfold in primitive form, and evolved through reconsolidated and reconstructed affective expressions, bit-by-bit. The transformation was long, slow, and painstaking. It involved regressing to entrenched knee-jerk emotional outbursts, and progressing to positive feelings and to conscious verbal descriptions of the feelings as they emerged. It evolved in an ontogenetic manner analogous to three developmental hierarchical processes: a primary system involving instinctive emotional actions; a secondary learning process; and a tertiary thinking and planning process.4

During the final years of treatment, neuropsychiatric literature began to reflect newly established neurobiological and neuroimaging methods for disclosing mechanisms underlying brain changes in psychotherapy.5,6 Studies showed that circuitry within the brain’s Extended Reward and Oversight System can be modified when negative automatic responses become positive and are mentalized, i.e., transformed into sematic representations.5,7,8 Dr. A was interested in understanding how mind/brain changes evolve through a relationship, and both Ms. Z and Dr. A gave permission to publish the present synopsis of their experiences during this transformative progression.

Therapy Years

Ms. Z did not know the origins of her debilitating and painful symptoms. She knew only that she was afraid of being with people with whom she wanted reciprocal love. For reasons unknown to her, Ms. Z had oscillated between extremes of idealization and devaluation of friends and sexual partners. She learned not to approach certain people, and to recoil at the first signs of perceived rejection, which were often imaginary. In defending herself against these increasingly agonizing yet amorphous feelings, Ms. Z intermittently became angry, accusatory, frightened, reclusive, and isolated. Eventually, her entrance pathway and exit pathway for each dissociation was anger. Her only alternative would have been to disconnect completely or to melt into a state of helplessness.

Ms. Z wanted to be free of the inability to face love and take it in. Although she hoped Dr. A would help her, Ms. Z soon began to feel love toward Dr. A and wanted love in return. It was the beginning of the essential transference/countertransference that enabled the journey to unfold in a safe setting. Not knowing the origin of her pain and fear, Ms. Z approached the therapeutic engagement slowly and cautiously. As Ms. Z’s affection for Dr. A grew, Ms. Z became unable to enter her office. Instead, she left notes at the door and sat outside in a waiting area for the scheduled therapy hours, to avoid facing her. The first sign of progress was when Ms. Z was able to enter Dr. A’s office for appointments. However, for many months, few if any words were exchanged. Next, Ms. Z began to talk while in a fetal position, with her arms or coat around her head. Dr. A listened, trying to fathom the agony.

Over the years, little by little, feelings emerged. Details of early emotional isolation and neglect came out. But occasionally, there would be an avalanche. During those terribly painful times, Ms. Z stalked her doctor; she waited secretly near Dr. A’s house, or hid near the office. Then there were years of unrestrained emotional outpourings. The dam had been breached. Throughout those sessions, the fears, the anger, the mistrust, the dread, the shame, seeped out from Ms. Z’s thoughts to her mouth. However, during those years there was no eye contact; Ms. Z could not look at Dr. A.

Unexpectedly one day, Ms. Z did look at Dr. A’s face and saw her eyes. Ms. Z saw the personification of the emphatic feelings previously perceived only in the form of Dr. A’s verbal intonations. And with each encounter, as pain, mistrust, and anger emerged, Ms. Z was able to feel safer, more understood, and more positively connected. Gradually, Ms. Z’s words began to come with more and more facility, and she was able to step back and begin to perceive both herself and Dr. A. Past diffuse emotional memories that had been clouded by years of protective defenses, began to be reactivated over and over and over, in a safe and supportive place. The once primitive feelings were tamer, less overwhelming, and verbalized. And slowly, very slowly, the feelings and memories of neglect became clearer. Within the therapeutic relationship, they began to be newly reconsolidated, loosening their original amorphous grip.

The intervention was not simple. It was through a series of patiently witnessed and accepted silences, confessions, outbursts, snooping, and the gamut of past memories and present thoughts. All the while, the evolution was buttressed by a safe small space and a welcoming person: not so much a doctor, but a friend. It was fueled by hope, newly combined with belief, that Dr. A was committed to trying to help her. And so, over time Ms. Z eventually became able to recall, reassess, and reconsolidate an experience of trust, comfort, self-perception, empathy, and love at autonomic, conceptual, and semantic levels. And during the final years, Ms. Z came to understand and believe that she, not her doctor, was in charge of her inner world of feelings, motivations, and thoughts. It was an essential change that allowed her to say good-bye.

Conclusions

Our fundamental emotional representations are pre-symbolic and hard-wired. They begin in infancy and are shaped by daily experience, which includes culture and language. If the infant’s daily life includes neglect, hunger, pain, fear, then it will not be able to consistently encode positive feelings. As maturation progresses, these feelings become associated with early painful memories, which in turn, can lead to chronic anticipation of aloneness and fear and result in damaging behaviors. However, in a safe place with a trusted ally, these early emotions can be reappraised, allowing memory traces to be reconsolidated in widespread brain networks.5,6,7 The transformation is gradual, because change can only occur slowly in those brain areas that are active in infancy. Neuroscientific evidence now offers a small window of replicable proof under controlled conditions, but reconsolidation of emotional representations also can be validated in the full splendor of human relationships. In other words, healing occurs with brain changes and the capacity for mentalization – the ability to have, share, and eventually verbalize dysphoric feelings in an environment of trust and true empathy. In turn, a new perspective of one’s emotions is formed, along with the power to decide what to do with them.

Dr. A: “I didn’t know where the analytic journey was going. I didn’t know what the end was. Our journey was founded on hope, and it has been a generative process for both of us. It has given me the understanding that mind and brain evolve together, and that empathy and love are humanity’s highest values. To have been a partner in this journey while witnessing the evolution of mind/brain has been one of the greatest privileges of my life.”

References

- Lane, RD, Ryan L, Nadel L, Greenberg L. Memory reconsolidation, emotional arousal, and the process of change in psychotherapy: New insights from brain science. Behav Brain Sci. 2015;38:1-64. doi:10.1017/S0140525X14000041, e1

- Beckers, T, Kindt M. Memory reconsolidation interference as an emerging treatment for emotional disorders: Strengths, limitations, challenges, and opportunities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2017;13:99-121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045209

- Cortina M. The future of psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychiatry 2010;73(1):43-56.

- Panksepp J, Biven L. The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotions. 2012. New York: WW Norton.

- Messina I, Bianco S, Sambin M, Viviani R. Executive and semantic processes in reappraisal of negative stimuli: Insights from a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Front Psychol. 2015;6:956-5668. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00956

- Viviani R, Nagl M, Buchheim A. Psychotherapy outcome research and neuroimaging. In: Gelo O, Prinz A, Rieken B, eds. Psychotherapy Research. Vienna: Springer; 2015:611-634. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-1382-0_30

- Makris N, Oscar-Berman M, Jaffin SK, Hodge SM, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Marinkovic K, Breiter HC, Gasic GP, Harris G. Decreased volume of the brain reward system in alcoholism. Biolog Psychiat. 2008;64(3):192-202. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.018

- Messina I, Sambin M, Beschoner P, Viviani R. Changing views of emotion regulation and neurobiological models of the mechanism of action of psychotherapy. Cog Affective Behav Neurosci. 2016;16(4):571-587. https://doi.org/10.3758 /s13415-016-0440-5

- Rivas-Grajales AM, Sawyer KS, Karmacharya S, Papadimitriou G, Camprodon J, Harris GJ, Kubicki M, Oscar-Berman M, Makris N. Sexually dimorphic structural abnormalities in major connections of the medial forebrain bundle in alcoholism. NeuroImage: Clin. 2018 (in preparation).

MARLENE OSCAR BERMAN, PhD, is a neuroscientist who directs a broadly based academic research program on brain-behavior relationships. Her group examines emotional and cognitive dysfunction in men and women with central nervous system disorders. Dr. Berman’s current research employs behavioral tests and neuroimaging measures of abnormalities in brain circuitry, in order to focus on the impact of long-term Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). These studies have shown clear sex-related differences in the brain and behavior of AUD patients, and suggest that other brain disorders also affect men and women differently.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply