Joshua Niforatos

Gregory Rutecki

Cleveland, Ohio, United States

|

| E.G.L. Bywaters. University of British Columbia, Open Collections |

The historian John Lukacs, a contemporary of pioneering British physician Eric G. L. Bywaters (1910-2003), wrote in his book At the End of an Age that “the history of anything amounts to that thing itself.”1 Lukacs, influenced by physicists Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, as well as Goethe’s Theory of Colors, made his observation discussing the history of quantum mechanics. In essence, to study the history of quantum mechanics is to study quantum mechanics itself. In the same way, to study the life of Eric Bywaters is to study the earliest history of rheumatology. But Bywaters’ place in medical history cannot be contained solely within the discipline of rheumatology. His contributions loom much larger, having also unfolded during World War II and the Blitz of London. As a consequence of the Blitz and epidemic crush injuries, the rheumatologist Bywaters also placed his clinical stamp on the syndrome of rhabdomyolysis and eventually dialysis as a treatment for acute renal failure.

Born in London, Bywaters received his medical training at Middlesex Hospital Medical School, receiving honors in pathology2 with an emphasis on biochemistry and hematology laboratory techniques.3 His early medical career was research-oriented. After medical school he worked as a pathologist with Dr. Lionel Whitby studying animal cartilage, assessing its metabolism and pathology.2-3 Working in Dr. Whitby’s lab in the 1930s, Bywaters was recognized by rheumatologist Dr. Walter Barr of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Barr extended an invitation to Bywaters to study cartilage in “larger animals.”4 At MGH, Bywaters became fascinated with rheumatology while focusing on patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. After the invasion of Poland by Hitler and the Nazi army in 1939, Bywaters returned to London to enlist and serve his country. But Bywaters was rejected from military service because of kidney disease.2 Dr. Bywaters was destined to find a way to serve, and in so doing, advance the cause of medicine while compassionately treating those afflicted by the vagaries of war.

Crush Injury: From Bedside to Bench and Beyond

Although he was not able to serve his country in uniform, Bywaters would take care of those who incurred crush injuries during the London Blitz as head of rheumatology at Hammersmith Hospital.

In his own words, Bywaters recalled patients he cared for with a crush injuries during the Nazi air raids.4 They were buried under massive amounts of rubble for prolonged periods.5-7 These patients were hemodynamically stable on arrival to the hospital but within a few hours experienced circulatory collapse, requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation. Every patient would die from uremia. With expertise in hematology laboratory methods, biochemistry, and pathology, Bywaters suspected that connections must exist between muscle trauma, consequent renal failure, and death.

|

|

| The Reconstruction of ‘an Incident’-Civil Defence Training in Fulham, London, 1942. WikiMedia. |

His theoretical construct proceeded as follows: the crush victim’s muscles were severely damaged and rendered ischemic. When the weight of the rubble was removed, the injured muscle was inundated with intravascular volume. The muscle swelled, was damaged further, and rhabdomyolysis occurred. Serendipitously, Bywaters accidentally left a solution of human muscle pigment from one of his patients in the refrigerator and noticed that the solution crystallized.4 The crystallized material was later discovered to be the muscle protein myoglobin. He identified myoglobin in the urine as well and differentiated it from hemoglobin. This differentiation was important since hemoglobin was also known to cause renal failure after mismatched transfusions.8-9 Myoglobin—in acidic urine–precipitated in the distal tubules and increased intrarenal pressure by tubular blockage, leading to acute kidney necrosis.

In 1941 Bywaters developed an animal model of the crush syndrome. Under anesthesia, rabbits were wrapped in a tourniquet producing occlusive pressures, followed by shock after release of the tourniquet.10-12 Unfortunately, the rabbits’ urines did not contain myoglobin. Thus, the last, essential ingredient in an animal model of crush syndrome was missing. When Bywaters injected rabbits with myoglobin in doses equivalent to those measured in crush syndrome victims, concurrent with an acidic solution and tourniquet-compression and release, renal failure was the result.10-12

As a biochemist, Bywaters used his animal model of crush syndrome to develop a treatment: he administrated alkaline solutions intravenously, immediately after crush injury, to protect the kidneys.13 From the bedside to the bench and back to the bedside, Bywaters’ care of patients and research-oriented pragmatism led to an understanding of the etiology and treatment of acute kidney injury consequent to rhabdomyolysis. His work as a “nephrologist” continued during this time period. Bywaters was the first physician in Britain to use the Kolff artificial kidney on patients with kidney disease.2

Bywaters’ investigations occurred while treating patients, and he was criticized by faculty at his institution. Bywaters remembered a professor of surgery who, during a lecture in front of a large audience, announced that Bywaters routinely collected “biochemistries and blood pressures” and was thus “misusing powers on injured people.” This surgeon went on to say that he would no longer admit patients to Bywaters’ ward. Bywaters was unmoved and continued his investigation of crush injuries and renal failure, performing his own autopsies on patients and studying their histopathology. Not only did the muscular damage appear similar in all his crush patients, but Bywaters observed that the kidneys of each patient had similar histopathological changes.12,14-15 Bywaters eventually termed this phenomenon “crush syndrome.”

Beyond Crush Syndrome

|

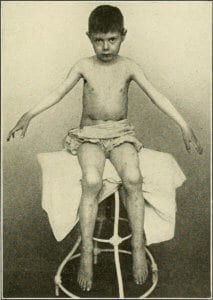

| Diseases of Children, 1916, shows a depiction of Still’s Disease. Edwin Eldon Graham. |

During his time at Hammersmith, Bywaters established a cohort of 200 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), diagnosed early in the course of disease. He followed this cohort for twenty years and would later receive the Gairdner Award for fundamental research impacting human health in 1968.2 This cohort of RA patients led to numerous studies that described the natural history of the disease and its morbidity and mortality. Bywaters continued to follow this cohort when, in 1947, he became director of the Special Unit for Juvenile Rheumatism at the Canadian Red Cross Memorial Hospital at Taplow.3 While in Taplow, in collaboration with U.S.-based researchers, Bywaters helped developed treatments for the systemic effects of rheumatic fever in children. His work demonstrated that cortisone improved symptoms of inflammatory joint pain, although it did not prevent the cardiac valvular disease of rheumatic fever.16-17 By the 1960s, the use of antibiotics to cure streptococcal infections and prevent sequelae of rheumatic disease resulted in an epidemiological shift in pediatric rheumatology from rheumatic fever to juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA), eponymously known as Still’s disease.

Bywaters’ medical legacy expanded with his work on JCA. Whereas other physicians saw both the early stages of JCA and severely crippled children with JCA as “hopeless” cases, Bywaters saw these children compassionately, in need of care.2,18-19 Children in pain were not confined to bed rest as was standard of care then; rather, Bywaters prescribed pharmacological pain control in concert with hydrotherapy to maintain mobility.2,18-19 For those crippled by JCA, Bywaters and his team of surgeon colleagues created the first custom-made artificial hips for children, followed by other prosthetic joints.2,18-19 Dentists at Taplow developed procedures to open stiffened jaws to administer anesthetics.2 Cataracts from the inflammation of JCA were effectively treated by ophthalmologists working with Bywaters. The work at Taplow established the field of pediatric rheumatology.

Bywaters recognized his professional strengths and weaknesses, allowing others to expand the molecular and immunological basis of disease. Known for his expertise in pathology, colleagues would frequently ask Bywaters for assistance in differentiating diseases pathologically.2 His work on tissue allowed clinicians to differentiate rheumatic fever from rheumatoid arthritis.20-21 Bywaters also wrote on characteristics of ankylosing spondylitis with information obtained from his own dissections.2 He developed some of the earliest methods for quantifying and categorizing osteoporosis.2 A PubMed search of Bywaters reveals essential publications on Still’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout and calcium pyrophosphate deposition, scleroderma, psoriatic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. These insightful manuscripts occurred at a time when rheumatology was not even considered a distinct discipline within medicine. While it is true that describing the etiology of diseases with rheumatic origins helped define rheumatology as distinct from general medicine, Bywaters was also an avid reader, medical historian, artist, and patient advocate. All of these attributes set him apart from other “fathers of medicine.”

Eric Bywaters: The Biography of Rheumatology

For twenty years, Bywaters served as the Honorary Heberden Librarian of the Royal College of Physicians.2 In his role as medical historian, Bywaters added depth to rheumatology by writing extensively on its history. Each disease Bywaters treated had its own unique biography. He published articles on the historical evolution of the concept of connective tissue disease, gout in the time and person of George IV, the historical aspects of ankylosing spondylitis, the etiology of rheumatoid arthritis, and a historical perspective of crush syndrome. Bywaters traced the development of rheumatology throughout history from books in the late 1600s to the evolution of journals.20 He wrote on the history of pediatric rheumatology,23 as well as memorializing rheumatologists such as George Frederic Still24 through thoughtful obituaries in academic journals. In an obituary written on Bywaters in 2003 in Rheumatology, the author recounts what Bywaters would most like to be remembered for: “for ‘seeding’ rheumatologists and rheumatology expertise throughout the world… Bywaters counted 349 trainees over his period of service and he was later able to visit many of them in their own countries and universities.”2

Dr. Eric Bywaters was unique both as a human being and a physician-scientist. His story can stimulate others in medicine to contribute to healing, service, and advancing knowledge and education during times of war and of peace.

Endnotes

- Lukacs J. At the End of an Age. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002. Page 53.

- Dixon A. Obituary: Eric Bywaters 1910-2003. Rheumatology. 2003; 42:1025-1027.

- Dixon A. Eric Geroge Lapthorne Bywaters. Br Med J. 2003 Jun 28; 326(7404):1461.

- Eric Bywaters Interviewed by Dr. J.S. Cameron. International Society of Nephrology Video Legacy Project. Accessed on December 15 at: https://cybernephrology.ualberta.ca/ISN/VLP/Trans/Bywaters.htm

- Bywaters EGL, Beall D. Crush injuries with impairment of renal function. Br Med J. 1941 Mar 22; 1(4185):427-432.

- Beall D, Bywaters EG, Belsey RH, Miles JA. A case of crush injury with renal failure. Br Med J. 1941 Mar 22; 1(4185):432-434.

- Bywaters EGL. Crushing injury. Br Med J. 1942 Nov 28; 2(4273):643-646.

- Bywaters EGL. Ischemic Muscle Necrosis. JAMA. 1994; 124:1103-1109.

- Peiris D. A historical perspective on crush syndrome: the clinical application of its pathogenesis, established by wartime crush injuries. J Clin Pathol. 2017; 70(4):277-281.

- Bywaters EGL, Popjak G. Experimental crushing injury. Surg Gvnecol Obstet. 1942; 75:612-627.

- Bywaters EGL, Stead JK. The production of renal failure following injection of solutions containing myohaemoglobin. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1944; 33:53-70.

- Bywaters EGL. 50 years on: the crush syndrome. Br Med J. 1990; 301:1412-1415.

- Better OS, Stein JH. Early management of shock and prophylaxis of acute renal failure in traumatic rhabdomyolysis. N Engl J Med. 1990; 322:825-9.

- Bywaters EGL, Dible JH. The renal lesion in traumatic anuria. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1942; 54:111-20.

- Bywaters EGL. Hydronephrosis: histological resemblances to late changes in the crush syndrome kidney. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1945; 57:394-5.

- Bywaters EGL. The Present Status of Steroid Treatment in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965; 58:649-652.

- Ansell BM, Bywaters EG. Alternate-day corticosteroid therapy in juvenile chronic polyarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1974 Jun; 1(2):176-186.

- Bywaters, EGL. Child Care in General Practice: Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Br Med J. 1965 Jun; 5451:1655-1657.

- Bywaters EGL. The management of juvenile chronic polyarthritis. Bull Rheum Dis. 1976; 27(2):882-886.

- Bywaters EGL. Current concepts concerning the pathogenesis of rheumatism. Trans Med Soc London. 1972; 89:248-254.

- Bywaters EGL. Historical aspects of the aetiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1988; 27 Suppl2:110-115.

- Bywaters EGL. History of books and journals and periodicals in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991 Jul; 50(7):512.

- Bywaters EGL. The history of pediatric rheumatology. Arthritis Rheum. 1977 Mar; 20(2 Suppl):145-152.

- Bywaters EGL. George Frederic Still (1868-1941): His Life and Work. J Med Biogr. 1994 Aug; 2(3):125-131.

JOSHUA D. NIFORATOS, MTS, is a medical student at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine. Born and raised in the suburbs of Chicago, he eventually made his way to University of New Mexico (UNM) where he earned bachelor degrees in both ethnology and biology. He then went on to earn a Master of Theological Studies at Boston University School of Theology where he studied theology, anthropology, and ritual.

GREGORY W. RUTECKI, MD, received his medical degree from the University of Illinois, Chicago in 1974. He completed Internal Medicine training at the Ohio State University Medical Center (1978) and his fellowship in Nephrology at the University of Minnesota (1980). After twelve years of private practice in general nephrology, he entered a teaching career at the Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, and the University of South Alabama in Mobile, Alabama. While at Northwestern, he was the E. Stephen Kurtides Chair of Medical Education. He now practices general internal medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply