Matthew Migliozzi

David Forstein

Sarah Rindner

Robert Stern

New York City, New York, United States

Historically, Jewish contributions to public health measures have not been given adequate attribution. The previous articles in this series have documented (1) the ancient Jewish recognition of the importance of isolating individuals with an infectious disease; (2) recognition of tuberculosis as an infectious disorder that could be transmitted to humans from tuberculous cows; and (3) the washing of hands as a public health measure. Now, we document the recognition of an inherited disorder, hemophilia, through careful observations associated with ritual circumcisions, the “brit milah.”

The Bris: Jewish Ritual Circumcision

References to circumcision occur in the Old Testament. According to Genesis, God told Abraham to circumcise himself and his household as an everlasting covenant in their flesh.

Genesis 17:10-14: This is my covenant with you and your descendants after you, the covenant you are to keep: Every male among you shall be circumcised. You are to undergo circumcision, and it will be the sign of the covenant between me and you. For the generations to come every male among you who is eight days old must be circumcised, including those born in your household.

The clotting mechanism does not mature until five to seven days after birth

Modern clinical chemistry documents that the clotting mechanism does not mature until at least five days after birth.1 The important clotting factor fibrinogen is the soluble precursor protein for the insoluble fibrin that creates the meshwork preventing further bleeding. It reached a maximum around day five. Similar profiles have been documented for factors II, IX, and XIIIb.

Careful observation by the ancient Israelites probably established that ritual circumcision, referred to as the bris or brit milah, be delayed until one week after birth.

Hemophilia A

Hemophilia A is an X-linked disorder involving an error in one of the key steps in the clotting cascade. It is the most common of the human bleeding disorders, caused by a mutation in clotting factor VIII. These X-linked disorders are passed down from mothers to sons. Since the potential lesion is on one of the mother’s two X chromosomes, there is a 50% chance that a son will inherit that chromosome. Males have an XY chromosome configuration and are therefore affected by the condition if the lesion is inherited. Women are protected by having a second normal X chromosome.

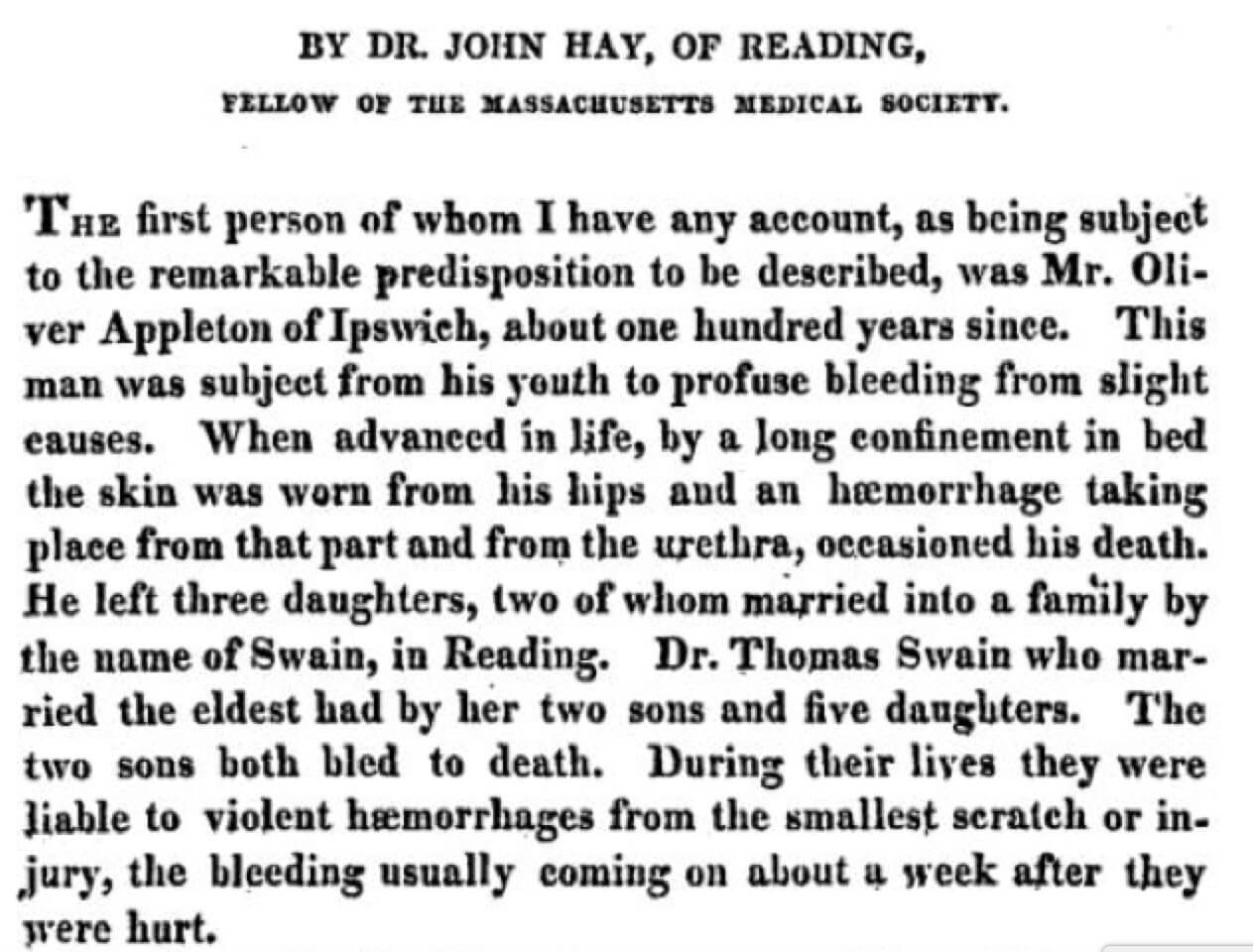

Hemophilia A was first described by the American physician John Conrad Otto. He described a bleeding disorder that ran in families and mostly affected the men, published in the Medical Repository in 1803. John Hay of Massachusetts later published an account of a “remarkable hemorrhagic disposition” in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1813.2

Queen Victoria passed this X-linked condition to her daughters and many of her grandsons. affecting the royal houses of Europe. Alexei, the Tsarevitch of Russia and young son of Tsar Nickolas II, had hemophilia.

Since there is a 50% chance of a son developing this X-linked disorder, before our modern concepts of genetics such a distribution would have been difficult to understand and predict. Yet there is written evidence that the ancient Hebrews, through careful observation, perceived some pattern of familial distribution.

References to circumcision and hemophilia in the Talmud

In the Talmud, in Tractate Yevamot 64B,3 it is taught: If a woman circumcised her first son and he died, and her second son and he too died, she should not circumcise her third son, so taught Rebbi. Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel stated that she should indeed circumcise her third child, but [if he died] she must not circumcise her fourth. Rabbi Yochanan said that there was once a case in Zippori in which four sisters had sons: The first sister circumcised her son and he died, the second sister circumcised her son and he died, the third sister circumcised her son and he died, and the fourth sister came to Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel and he told her, “You must not circumcise your son.”

The Talmud here is describing a disease that is transmitted through the maternal line (hence the four sisters—all of whom seem to pass this disease on to their male children). The description is consistent with X-linked hemophilia A. The rabbis argued over a technical point—that is, how many cases of bleeding are needed to establish a pattern. According to Rebbi (Rebbi Yehuda Ha-Nasi, c. AD 135–217) two cases were sufficient, while Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel, (10 BC–AD 70) insisted on three cases before ruling that there was a life-threatening pattern. Indeed the disease in boys must have been very perplexing, because not every boy would be affected. This perhaps explains the dispute between Rabbis Yehuda Ha-Nasi and Shimon ben Gamliel regarding how many children need to exhibit the disease before it can be assumed that any future male child will also have it.

Earlier, the Mishnah,* in Yevamot, records the case of a priest that was not circumcised because of the deaths of his brothers when they underwent the procedure. So this law was certainly practiced in even earlier times. But the important point is that the Talmud records the earliest known description of an X-linked disorder such as hemophilia. In addition, it emphasizes the preservation of life as a normative Jewish practice.

*The Mishnah consists of 63 tractates codifying Jewish law, which are the basis of the Talmud. The Mishnah was compiled by Rabbi Yehuda Ha-Nasi (Rabbi Judah, the Prince) in the year 3949, which corresponds to 189 CE.

Conclusions

The Jewish ritual of circumcision, or “brit milah” is performed on male infants on the eighth day following delivery. The clotting mechanism, immature at birth, reaches maturity at about that time. The Talmud recognizes that some bleeding disorders have a genetic basis. This may be the first time in history that certain human disorders have been recognized as having a familial or genetic basis. This is a conclusion that could only have been reached through careful observation over many generations.

References

- Andrew M. et al., Blood, 70: 165-172 (1987).

- Hay J. New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. II: 29-30 (1813)

- http://www.talmudology.com/jeremybrownmdgmailcom/2014/11/27/circumcision-death-and-hemophilia-a

MATTHEW MIGLIOZZI, M.S., is a 2nd year medical student at the Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine (Touro COM) in New York City.

DAVID FORSTEIN, D.O., is Dean and Professor at Touro COM.

SARAH RINDNER, M.A., is a Professor teaching English Literature at Lander College for Women, Touro University.

ROBERT STERN, M.D., is Professor in the Department of Basic Medical Sciences at Touro COM.

Leave a Reply