Daly Walker

Boca Grande, Florida and Quechee, Vermont, United States

|

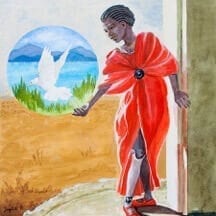

Most memories pass on to oblivion without changing anything. But some are so powerful they transform who you are. They never leave you. Without my memories of a girl named Jane, I would never have become the doctor I am.

On a clear December morning fifty-six years ago, I was a floundering pre-med freshman at a small liberal arts college in Ohio. In front of a great stone library, I looked up and saw Jane, long-legged in a camel coat and long knit scarf. Whorls of blonde hair spilled from under her stocking cap. I thought she was almost pretty in a fresh, freckled way. A sudden gust of cold wind scattered leaves across the sidewalk. I noticed that her eyes were red and tearing. The beads of moisture on her cheeks stabbed my heart, and wondered why she was crying. What a beautiful and sensitive person she must be, I thought. I would like to get to know her.

The next time I saw Jane was at a Christmas mixer in my federalist brick fraternity house. In a dimly lit recreation room, we sat on an old leather sofa. A Johnny Mathis Christmas album was playing on the stereo. It seemed she wanted to tell me everything about herself. She was majoring in elementary education. Her father had died in his forties of a heart attack. Her widowed mother lived with her younger brother in Columbus, Ohio. Then she said, “But why don’t you tell me about you?” I told her I was pre-med but thinking of changing my major. She said I would be crazy not to be a doctor if I could. I mentioned the tears I saw in her eyes that day near the library and how moved I had been. She smiled and told me she had actually been quite happy that day. The cold wind had brought the tears to her eyes. Before long, the current of her charm swept me downstream. I asked her to dance. I held her close. Our cheeks touched, and she hummed softly to the music. I closed my eyes and wished. Johnny Mathis was singing “The Most Wonderful Time of the Year.”

We began dating—bowling at the Memorial Union, movies at the Strand, drinking beer at the Brown Jug. She insisted that we study together nearly every evening. I gazed at her across the library table, transformed by those beautiful long legs, her exuberance and spontaneity, and terrific sense of humor. With her encouragement, my grades improved—I made the dean’s list. Once again I aspired to a doctor’s life.

During the following two years our love deepened. By the end of junior year we began making plans to marry. I hoped I would be going to medical school and Jane would teach elementary school nearby.

The summer between junior and senior years, I hitched a ride to Boulder where I studied physics and worked as a waiter. Jane and my sister were off to Hawaii for summer school and beach time. Nearly every day, she sent me a letter of love and longing. Toward the end of her time in Hawaii she wrote:

My Dearest

I have developed a pain in my knee. The doctor at student health says it’s a sprain and nothing to worry about. He gave me an ace bandage to wear. I sit here looking at your picture and wishing you were here. I miss you so much. We have so much ahead of us.

Love Jane

The ache in Jane’s knee, the one she tried to rub away with wintergreen, soon became an unrelenting deep bone pain. She flew home to Ohio and saw an orthopedic surgeon at University Hospital. An x-ray of her leg showed a tumor in her femur. The following day a biopsy was taken under anesthesia. The diagnosis was osteogenic sarcoma, a malignancy of the bone. When she called to tell me they were going to amputate her leg above the knee, I dropped into a chair, stunned. I heard myself saying I would leave early in the morning for Columbus, that I loved her and everything would be all right. I heard her weeping. I hung up in total disbelief. It was impossible for me to think of Jane without her beautiful long leg. She was so young. Surely it wasn’t true. The next day I drove a Volkswagen Beetle straight through from Colorado to Ohio.

The amputation went without complication. Her stump healed quickly, and soon she was walking with an artificial leg, its hinged knee joint ticking softly like a timer. For a while the nerve endings at the amputation site continued to send signals to her brain, creating a phantom pain. The memory of pain and the pain of memory became more pain. Her body was mourning the loss of its limb.

She returned to school for second semester, still on track to graduate. Her prosthesis did not slow her down much. We were back studying together in the library, even bowling again. I was accepted by Indiana University Medical School. Jane began searching for a teaching job and an apartment for us in Indianapolis. At graduation, she gamely limped across the football field with me at her side to receive her diploma. The commencement speaker said the future was rich with opportunities. I believed him because when I had asked Jane’s doctors about her prognosis, they glossed over the truth. No one told me that there were virtually no survivors of osteogenic sarcoma.

Soon after graduation Jane begin to cough up blood. Snowballs of metastasis appeared in her lungs. An experimental treatment with intravenous radioactive pellets at New York’s Sloan Kettering failed to stop the malignancy’s spread. Her mother prepared a room on the first floor of their Ohio home with an Admiral television set and a double bed where Jane and I could be together for the time she had left. I found a job with a crew spreading asphalt on the berm of an interstate highway. When I came home from work tired and hungry, tar on my boots, Jane made dinner for me, something substantial: meat loaf, fried chicken, a cherry pie. We played honeymoon bridge in the evenings, then went to bed. We lay in the dark, our bodies pressed together. Her artificial leg, pink and plastic, laid on the shag carpet at the bedside like a mannequin’s extremity.

Jane died in August, and the world turned to darkness. Now I was the amputee. A critical part of me had been cut away, leaving me with phantom pain. Heartbroken, I started medical school in the fall. Memories of Jane bred an unbearable and inescapable loneliness in me. I read and reread her letters, stared at her picture, wishing. At times I thought I could not go on, and I considered dropping out of school. But Jane had wanted me to be a doctor, so I persisted.

Following medical school, I became a surgeon. While science informed me about disease, it was memory that shaped my response to the patient. Every time I amputated a gangrenous leg or operated on a patient with cancer, Jane was there at the bedside, urging me to be empathetic and honest, to listen and care. For several years I remained single, avoiding true intimacy and the risks it might present. Finally I married a fine woman and raised three lovely daughters.

Time passed. Old age seeped in. Memories of Jane were less frequent, less vivid, lurking as ghostly shadows in my brain. Proust wrote: “Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were.” In that regard, it was as if my time with Jane was an act of my imagination, a narrative from another life that seemed impossible for me to have lived. However, one day something happened that resurrected Jane in my consciousness and made her real again. Soon after her one-hundred year old mother died, Jane’s brother brought me a manila envelope crammed with memorabilia. I took the envelope to my desk. With trepidation I explored its contents, afraid of what the past might resurrect. There was a lock of Jane’s wheat blond hair cut in 1952 when she was twelve. There were photographs of Jane and me in togas and tipsy at a Fiji Island party, Jane in a white formal dress holding a bouquet of red roses while being serenaded on the steps of my fraternity house, Jane in Hawaii wearing Bermuda shorts, her knee bound in an ace bandage. A sepia-toned photo of a smiling little girl in a pinafore and pigtails stirred my heart. Her big brown eyes gazed beyond the camera as if something glorious awaited her. I recalled the tears I had seen in those eyes that cold day in front of the library, and I smiled because on that day she had also been happy.

DALY WALKER, MD, is a fellow of the American College of Surgeons and a retired general surgeon. His fiction has appeared in several literary publications, including The Sewanee Review, The Louisville Review, Catamaran Literary Reader, and The Atlantic Monthly. His work has been short listed for Best American Short Stories and an O’Henry award. His collection of stories, Surgeon Stories, was published by Fleur-de-lis Press. He divides his time between Boca Grande, Florida, and Quechee, Vermont. He teaches a fiction writer’s workshop at Dartmouth College in Osher at Dartmouth’s summer program.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 1 – Winter 2018

Fall, 2017 | Sections | Personal Narratives

Leave a Reply