John Ehrhardt

Patrick O’Leary

Miami, Florida, United States

|

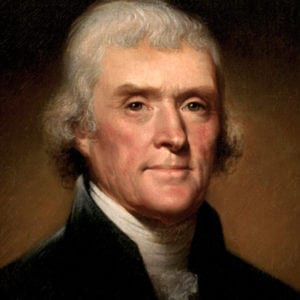

| Portrait of Thomas Jefferson |

Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence and third president of the United States of America, devoted much of his life to science, medicine, and education. Entering the College of William & Mary at sixteen, he was mentored in science and philosophy by Professor William Small. Though Jefferson became a lawyer, he never lost his fascination for these subjects. He read medical books and engaged in meaningful discussions with physicians throughout his life. In fact, he was an early visionary for medical education and healthcare in the United States.

Jefferson’s political career allowed him to draft legislation that influenced American medicine and the education of physicians. Along the way, he founded two medical schools: the College of William & Mary1 during the American Revolution and the University of Virginia during his retirement. The story of these two medical programs are a testament to his character as a founding father of the United States.

The School of Medicine at the College of William & Mary

During the early days of the American Revolutionary War, Jefferson left his seat at the Continental Congress of Philadelphia in October of 1776. Returning to Virginia politics, he began the task of reforming his home state’s legislation to reflect the core beliefs of political freedom he expressed in the Declaration of Independence. In June 1779 he was elected governor of Virginia. One month later, the Virginia legislature passed Jefferson’s Bill No. 80 calling for the reorganization of the College of William & Mary to establish a medical school.2 This became the third medical school in America, only preceded by the colleges of medicine in Philadelphia and at King’s College in New York.3 As Williamsburg was then capital of Virginia, the new governor was perfectly positioned to oversee the first class at the new school of medicine from his governor’s palace down the street.

Governor Jefferson appointed Dr. James McClurg as chairman of anatomy and medicine at the new medical school. The two had been classmates at William & Mary before McClurg went on to study medicine in Edinburgh. True to his roots, Dr. McClurg returned to Virginia to serve as a surgeon during the first half of the American Revolutionary War.4 He was ahead of his time in believing that medicine and surgery, despite the separations made in Europe, should be taught together. Beyond his reputation as a surgeon in Virginia, very few records remain from his time at the school of medicine.

Little is known about the curriculum or how many doctors graduated in medicine from William & Mary during these nascent years. As the American Revolutionary War progressed, the capital of Virginia was moved in 1780 from Williamsburg to Richmond. The redcoat invasion of the peninsula of Virginia, along with the siege of Yorktown that ended in October of 1781, left the College of William & Mary in shambles. After the war, Richmond was cemented as the new capital and Williamsburg became a shadow of its former glory. The College lost its support from their previous ties to Great Britain, and when it gathered enough strength to reopen it could no longer afford to maintain a medical school.2 Finally, in 1859 a fire destroyed the few remaining documents from the school of medicine that had survived the American Revolution.3

Though short-lived, the school of medicine at William & Mary is proof that Jefferson highly valued medical education. He was bold to charter a medical school during the height of the War for Independence to address the dearth of medical schools and, understanding the healthcare demands of the newborn nation, made an effort to produce educated doctors at that critical time. He was then one of the first Americans to focus on quality medical education and care.

The School of Medicine at the University of Virginia

Although Thomas Jefferson served in many powerful positions in American politics, he listed none of these on his self-designed tombstone. He wished to be remembered as the author of the Declaration of Independence, the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and as father of the University of Virginia.

Jefferson honed his interests in medicine, technology, and education during his roles as minister to France and later as secretary of state. He dined with the greatest academic minds of Europe, who planted the seed for how he would create his ideal university. Years later, when choosing the department chairmen of each school, Jefferson faced harsh criticism for appointing foreign European professors in his new American university.5,6 To lead the medical school he appointed an Englishman named Dr. Robley Dunglison.7

When Jefferson founded the University of Virginia in 1819, Charlottesville would have seemed an unlikely place for a medical school.8 It would have been easier to erect a medical school in a large city with the population to support a hospital. But Jefferson understood the need to produce physicians who would serve the rural communities of Virginia. As a former president who held close relations with the US Navy, Jefferson knew that the bustling naval shipyards of Norfolk could provide significant clinical opportunities for the students, but the plans for having clinical rotations there came to naught. Although many people were doubtful of the school’s ability to survive without a hospital, these circumstances became a blessing in disguise.

Although the University of Virginia lacked a hospital when it opened, there was a dispensary on campus where the students learned materia medica (therapeutics) and pharmacy from Dr. John Patton Emmet, the first professor of natural history. After class, medical students were required to stay and serve the community of Charlottesville by providing medical advice and dispensing medications to locals who came to visit.9 Patients able to pay were charged only fifty cents. Jefferson was the son of a farmer, and his medical school reflected his sensitivity to the needs of the average American.

Without a hospital, the medical curriculum adopted a unique focus on theory that was uncommon among the American medical schools of the era. Virginia students studied more basic medical science than the medical students at northern schools, and their academic sessions were longer and more intensive. The academic curriculum at the University of Virginia ran ten months out of the year, as opposed to six months at other medical schools. The University of Virginia provided medical education that was:

“…for gradual acquiring, and thereby [facilitating the] digesting of information conveyed by oral instruction, without the confusion of thought and fatigue of mind which are inevitable, when, as always happens in city schools, one has to encounter daily six or seven lectures delivered in rapid succession.”9

Not surprisingly, it was found that medical students from Charlottesville had a greater knowledge of science than those from other schools. When some students later transferred to Philadelphia for clinical training, they were said to be among the top of their class.9 Overall, the medical students in Charlottesville were not distracted by the luxuries of a city, nor did they have to balance clinical duties with the study of medical theory.

During 1825, the first year the school matriculated a class, the students petitioned to have school cancelled on the Fourth of July. Dr. Dunglison sent a letter up to the hill to Mr. Jefferson at Monticello. The author of the Declaration of Independence and Father of the University responded by writing:

“…The thread of their studies is broken, and more time still to be expended in recovering it. This loss, at their ages from 16, and upwards, is irreparable to them. Time will not suspend its flow during these intermissions of study.”10

In essence, Jefferson valued the education of future physicians more than he valued the importance of a holiday put in place to commemorate his writing of the Declaration of Independence. Through the hard work of the students and faculty, the School of Medicine awarded four doctor of medicine degrees in 1828,9 two years after Jefferson’s death, to the first graduates of the University of Virginia.

Over the course of his dynamic career, Jefferson used politics as a means to express his values on the importance of healthcare and education. He once wrote, “…you may promise yourself everything—but health, without which there is no happiness. An attention to health, then, should take place of every other object.”2 The two Virginia medical schools Jefferson founded reflect his integrity and illustrate his compassion for the needs of the American public.

References

- Blanton WB. Medicine in Virginia in the Eighteenth Century. Richmond: The William Bird Press; 1931.

- Shield JA. Jefferson’s School of Medicine at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. Virginia Medical Monthly, 1968; 95(2): 88-93.

- Thorup OA. Thomas Jefferson: Founder of Two Medical Schools. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1981; 92:16-22.

- Slaughter RM. “McClurg, James (1746-1832).” In: Kelly HA, Burrage WL. American Medical Biographies. Baltimore: Norman, Remington Company; 1920: 731–732.

- Shryock RH. Medicine and Society in America: 1660-1860. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1962.

- Eckman J. Anglo-American Hostility in American Medical Literature of the Nineteenth Century. Bull Med Hist 1941, IX: 31-71.

- Radhill S. The Autobiographical Ana of Robley Dunglison, M.D. The American Philosophical Society; 1963.

- Malone D. Jefferson and His Time: The Sage of Monticello. Boston: Little, Brown; 1970: 411-425.

- Bruce PA. History of the University of Virginia, 1819-1919: The Lengthened Shadow of One Man, Volume II. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1921: 105-116.

- Dorsey J. The Jefferson-Dunglison Letters. Charlottesville: The University of Virginia Press; 1960.

JOHN D. EHRHARDT, JR. is a medical student at the Florida International University Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine. He studied biomedical sciences at the University of Central Florida, where he cultivated a passion for medicine through his service in clinics for the uninsured. His teaching positions in the basic medical sciences during college and medical school have influenced his decision to pursue a career in academic medicine.

J. PATRICK O’LEARY, MD, FACS, received his medical education and residency in General Surgery at the University of Florida. In 1989, he was appointed to the Isidore Cohn, Jr endowed chair and chairmanship of Department of Surgery at LSUMC, New Orleans. He has held numerous leadership positions in national and international surgical organizations including the first vice presidency of both the ACS and the SSA. He has received the Distinguished Service Award for the SMA and the SESC. Of late, he served as the founding Executive Associate Dean for Clinical Affairs for the recently created Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine at Florida International University.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 3 – Summer 2018 and Volume 15, Issue 2 – Spring 2023

Summer 2017 | Sections | Education

Leave a Reply