Christopher Magoon

Philadelphia, PA, USA

For many of the non-Chinese volunteers who aided China during the tumult of the 1930s and 40s, a notoriety that borders on mythology remains to this day. Perhaps most famously, an American group of volunteer fighter pilots known as the Flying Tigers still enjoys rockstar levels of fame in China. This American group helped resist the Japanese invasion before the United States entered WWII, and their legacy is ubiquitous across present-day China. Dedicated museums and exhibits are scattered throughout the country, and a major motion picture is currently in production.1

Another example of modern fame is Dr. Norman Bethune. A Canadian physician who died from an infection in 1939 while tending to Chinese soldiers, Dr. Bethune is revered as the ideal public servant with numerous statues and buildings named in his honor. For decades Chinese school children were required to memorize a eulogy of Dr. Bethune, which reads in part, “We must all learn the spirit of absolute selflessness from him.”2 China’s highest medical honor is now called the Norman Bethune Medal.3

There are many more examples of revered non-Chinese from that era, but for the volunteers of the Friends’ Ambulance Unit there are no museum exhibits, famous eulogies, or movies in their memory. The group served in China from 1941 to 1950 and shared the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts, and yet only a smattering of limited circulation books have been published on the group, which are now almost all out of print. This small historical spotlight stands in stark contrast to their contributions, as the group was responsible for distributing nearly 80% of all medical supplies in nationalist China.4 Despite their impact, the Unit’s buildings have been demolished without a wisp of memory. A dedicated researcher must spend days looking for evidence of their existence.

One such researcher recently did seek out remnants of the Unit, and he found Mrs. Yu Zheng Yin, an octogenarian who remembered the Unit well. She recalled how her little brother was taken to the Friends’ Ambulance Unit South Bank Clinic and had his life-threatening measles treated for only four cents. This was a particular relief to her parents because her six other siblings had already died of disease.

Though no plaque or monument marks the location, Mrs. Yu’s brother is still alive today, and she will not forget that he and many thousands of others were treated by the Friends’ Ambulance Unit South Bank Clinic.

At its peak, the Friends Ambulance Unit delivered medical aid across a network that spanned nearly 4,000 miles and contributed the majority of medical supplies delivered throughout nationalist China. However, as communist forces gained territory over their nationalist foes, travel throughout the area was restricted. With the communists on the verge of victory in 1949, most non-Chinese aid workers, missionaries, and advisors formed a mass exodus, fleeing the unknowns of socialism. Rather than leave, the Friends’ Ambulance Unit stopped delivering medical aid and opened their own clinic to administer the remaining supplies themselves. This essay will focus on this clinic, which was open for less than a year but remains a telling chapter in the history of a little known group of pacifists who chose to stay despite harsh conditions and the dangers of being caught between a retreating nationalist army and the unknown reign of the communist government.4

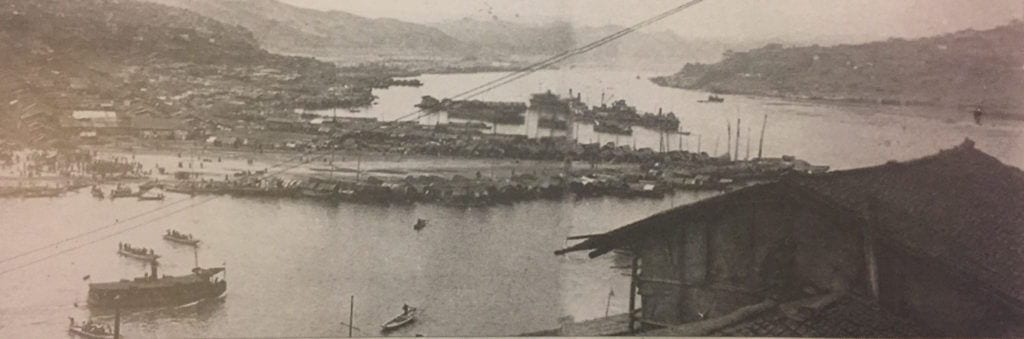

The South Bank Clinic, named for its position on the Yangtze River in the city of Chongqing, initially opened in an old warehouse on November 5th, 1949. The group was run by a Quaker aid organization, and its members were pacifists and strictly neutral. The city of Chongqing was a final holdout of the nationalist forces under Chiang Kai-shek, who would retreat to Taiwan mere days after Chongqing fell to the communists.

The clinic staff lived in accommodations that can be generously described as rustic. One member of the clinic wrote home cheerily describing their beds as “covered with netting, not so much to keep out the mosquitoes, but they prevent the rats which scurry across the ceiling beams from falling directly on us when they lost their footing.”4 Unable to tolerate difficult conditions, noting especially the putrid latrines, the only doctor at the clinic left after less than two weeks.

In the weeks following the doctor’s departure, a lab technician arrived via Hong Kong, followed by a philosophy PhD who was recently released from a yearlong prison sentence for refusing to register for the draft, and his wife. All together there were seven foreign volunteers on staff, each with their own unique and often extraordinary path to this particular corner of the world at this particular time. Though relatively well supplied, only one volunteer, the lab technician named Fleda Jones, had any medical experience prior to joining the Unit and none were fluent in the local language.

Within days of the newcomers arrivals, the surrounding fighting grew closer and more constant. They decided to move the clinic to a shelter within their compound. Unit leader Jack Jones described the move, writing in a monthly report, “There was a big red cross on the door and a notice saying it was the FAU Poor People’s Clinic. We had supper by candlelight to the music of continuous machine gun fire and explosions, and the next morning we woke up to find Communists soldiers in the yard.”4

In the evenings, Jack and Fleda would be called away nearly nightly to a miscarriage or delivery. From these private excursions, with “lovely blood all over the place,” as Jack described, Jack and Fleda struck up a brief romance, playing cribbage by candlelight after returning.

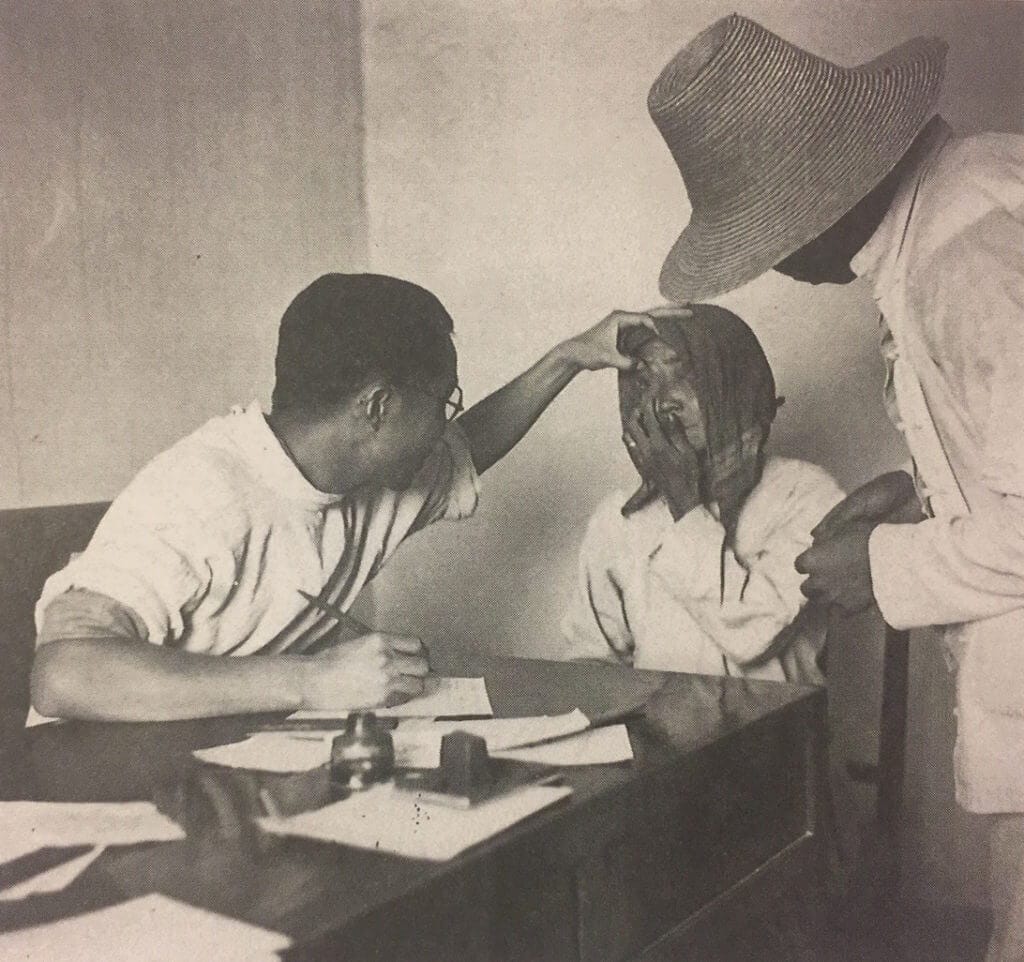

Unit volunteers witnessed the crushing poverty of the time. In those years finding dead bodies abandoned on the streets was an everyday occurrence, leaving the observer to reflect on the blurred distinction between desperation and disease.5 A Unit volunteer mused in a letter home, “Existence here for these people is unadorned simplicity, a round of birth, childhood, work, procreation, and death, lavishly sprinkled with empty tummies, cold toes, and dirty sores.”4 The ailments they treated were a reflection of the difficult times. “Real and horrible are the sores of China that come to us day after day; bodies deeply pitted with nauseous ulcers, usually covered with a foul rag,” described one member. Numerous members wrote that they hoped that the new communist government was up to the task of managing this area, as change was so desperately needed.

For about six months the clinic operated with high patient volumes without government interference. They secured an operating permit from the communists, but slowly they began to notice increasing numbers of placards around the city discrediting their organization with charges of amateurism that were hard to refute given the lack of a staff doctor. Friendly relations took a sharp decline in June of 1950 when the Korean War began, making America a formal enemy to China. One month later the clinic team secured a full time doctor who was fluent in the local language, and the clinic itself ran better than ever. Unfortunately, the country was already swept up in an anti-foreign zeitgeist, which included foreign medical missions. In December of 1950 Dr. Stewart Allen, a Canadian missionary physician also in Chongqing, was imprisoned by his own staff and spent a year in solitary confinement.

The same month, the Unit closed. At this early hour in the Cold War, international skepticism had already conquered international goodwill. All equipment and Chinese staff were shipped to an industrial cooperative, while the foreigners had to wait in austerity for exit permits. For months, they huddled around an empty oil drum which they converted into a stove and navigated the bureaucratic hurdles necessary to leave the country.4

Leaving under these terms, it is unsurprising that the Unit would be omitted from Chinese state curricula and memorials. However their story is ultimately one of international cooperation. In the present era, such examples are welcome more than ever. The brief, flourishing existence of the Friends’ Ambulance Unit South Bank Clinic is a story of selfless devotion on par with the Flying Tigers and Dr. Norman Bethune. Though the Unit’s pacifist volunteers entered a warzone and stayed when others left, they are largely forgotten. For now at least, their devotion has outstripped their legacy.

Note

* The official name of the Friends’ Ambulance Unit changed to the Friends’ Service Unit in 1946, however many members continued to refer to their organization by the original name. I have chosen to refer to the group by Friends’ Ambulance Unit throughout this essay for consistency and clarity.

References

- Kroll J. Skydance, Alibaba Team Up on World War II Movie ‘Flying Tigers.’ Varietyhttp://variety.com/t/the-flying-tigers/. April 6, 2016. Accessed December 20, 2016.

- Avery M. From Bethune’s Birthplace to the PR China. Lulu. 2013. https://books.google.com/books. Accessed December 22, 2016

- Tan SY, Pettigrew K. Henry Norman Bethune (1890–1939): Surgeon, communist, humanitarian. Singapore Medical Journal. 2016;57(10):526-527. doi:10.11622/smedj.2016162.

- Hicks, Andrew, ed. Jack Jones: A True Friend of China, the lost writings of a heroic nobody. Earnshaw; 2015.

- Goldkorn J and Guo K. Interview with Sidney Rittenberg. Sup China http://supchina.com/sinica/sidney-rittenberg/. January 19, 2017. Accessed January 21, 2017.

Photo source

Hicks, Andrew, ed. Jack Jones: A True Friend of China, the lost writings of a heroic nobody. Earnshaw; 2015.

CHRISTOPHER MAGOON is a third year medical student at the Perelman School of Medicine. Before attending medical school, he worked in rural schools in Western China after receiving a degree in History from Yale University. While in China, he immersed himself in the stories of the people who lived there, past and present. He extends his sincere appreciation to all those who have colored his many journeys.

One response

I was lucky to find this article under the hot word of Friends ambulance unit in China and had read it more than once. It is fascinating to say the this part of story or history is almost forgotten. But, there are some exhibitions in some public museums on this topic, such as Xian 8Th Army Office Museum (Xian Baban Museum), etc. They tended to introduce only little portion of FAU Convoy by only on MT19.

There is good news that the book, as it is listed in the reference list at the end of the article, named: Jack Jones A True Friend to China, the Lost Writings of an Heroic Nobody by Professor Andrew Hicks is now published in Chinese and will be available to the readers soon.