Fergus Shanahan

Ireland

|

One of the poems written by Seamus Heaney after recovering from a stroke was inspired by the well-known biblical story in which a sick man is miraculously cured. However, the Nobel laureate was drawn neither to the patient nor to the healer—“not the one who takes up his bed and walks”—but to those in the background, ordinary people there to provide support: “the ones who have known him all along.”1 The poem is a gesture of gratitude to those who support by their presence and wait: “be mindful of them as they stand and wait.”

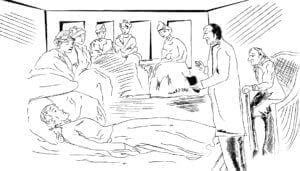

In most illness stories, the main protagonists are the patient and the doctor or caregiver, and their relationship is rightfully regarded as an area of medicine likely to undergo radical change in the future.2 Less attention has been paid to the role of the supporting cast in the illness story: the friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. Everyone at some stage will be a participant in the story of an illness. The manner in which we play that role may either mitigate or accentuate the stigma and isolation of illness. Illness creates a sense of loss and suffering that is inescapable, but some aspects of the ordeal are avoidable because they are products of the behavior of the supporting players and the attitudes of society toward illness.

How to behave with the ill: “Approach us assertively”. . . “Be direct,” and don’t “cringe or sidle . . . or scurry past” declared the poet Julia Darling, who died from breast cancer.3 Most important—try not to ignore the ill. The rationalization that nothing can be done is no refuge, nor is the convenient assumption that the sick wish to be alone. Engage. Be there.

News of a serious personal illness is often accompanied by an instinctive response to conceal it. For some, this is because of confusion, vulnerability, and concern for loved ones; but for others, it is to avoid the awkwardness of changed relationships with friends and acquaintances. Serious illness is associated with a heightened sense of awareness, apprehension, and even embarrassment in anticipation of how others will react. The illness label represents a new kind of stigma, a transition to the other world of patients, distancing the sufferer from friends and others. Having a disability is similar.

In Alan Bennett’s memoir of first being diagnosed with colon cancer, he recalls that even the doctor’s receptionist found it hard to look directly at him when he was paying his colonoscopy bill, and that he in turn felt shame and a sense of failure.4 A sense of shame and embarrassment was also experienced by Robert McCrum while recovering from a disabling stroke as a young man.5 His description of the reactions of others to his condition is troubling: “the majority of passers-by simply do not see the disabled person, and/or threat you with a mixture of ruthless disdain and pitying arrogance.” Similarly, in the 2010 film The King’s Speech, the reaction of others compounds the stigma of disability when a young prince and future king, handicapped by a severe stammer, is called to deliver a speech before a crowded football stadium. Struggling to enunciate syllables, his anguish intensifies on seeing the responses on the faces of those gathered to listen, looking downward, then away in disappointment and embarrassment.6

Illness narratives illustrate the acute sensitivity of the sick and disabled to subtle changes in behavior of others in response to their misfortune. Words and gestures adopt uncommon significance. Compassion is always appreciated and can be sensed, but the sick need no idle chatter. Companionship, or simply being there, is sufficient support. In a good humored commentary on his illness with advanced esophageal cancer, Christopher Hitchens found that “the presence of friends” was his chief consolation but considered whether there should be “ground rules” on etiquette for how sympathizers and sufferers of cancer should interact.7 His proposed etiquette handbook would provide guidelines to address the “inevitable awkwardness in diplomatic relations between Tumortown and its neighbors.” He was assailed with advice and rumors of cures which were well-intended but tedious. Referring to the lingua franca of Tumorville as “dull and difficult” he found jaded clichés and exhortations intended to boost morale as “vaguely depressing.” Likewise, he declares that grave illness makes one suspicious of popular expressions of received wisdom regarding health. He recommends we avoid them. Vacuous stories of others with the same or similar illnesses do not provide much succour to distressed patients trying to cope with a grave illness. Anatole Broyard also wrote of being regaled with the stories of others after his diagnosis with metastatic prostate cancer: “Storytelling seems to be a natural reaction to illness. People bleed stories, and I’ve become a bloodbank of them” but on the other hand, “. . . anything is better than an awful silent suffering.”8 According to Alan Bennett: “There is no fellowship in suffering. . .”.4 Of course, there are always exceptions, even room for humor. During rehabilitation in hospital after his stroke, Seamus Heaney was visited by his friend, the playwright Brian Friel, who had also suffered a stroke a year earlier, and who remarked: “different strokes for different folks.”9

It might be assumed that leaders within the caring professions would be most conscious of their behavior with the ill and should know what is required. Curiously, some clinicians never contemplate the influence of their behavior or how they should act when dealing with patients, friends, and colleagues afflicted with serious illnesses. Testimony from doctors who develop serious illnesses highlights the isolation, soft bigotry, and discrimination that may be experienced when news of their illness becomes known to colleagues.10-12 Variable as the experience of illness may be, a consistent feature of doctors’ stories is the comfort of knowing that friends and colleagues care. The more it seems that nothing can be done, the greater, not lesser, the role of support from friends and colleagues.

One story, that of David Rabin, is particularly disturbing, even on re-reading more than thirty years after it was first published.12 Rabin was the senior endocrinologist at a major teaching hospital when he developed motor neuron disease. Like others, he describes avoidable and distasteful aspects of his illness, which arose because of the change in his interrelations with colleagues after he was diagnosed. Relationships that were once close with some colleagues, deteriorated. Few called or visited: “Why this deafening silence?” Although the illness was incurable, Rabin claimed “there are so many ways colleagues can help . . .” The most chilling part of his story is the day he fell at work. As he lay on the ground, a fellow physician ignored him, hurried past with eyes quickly averted pretending not to notice.

How to behave with the ill: “it’s not easy I know” conceded Julia Darling.3 It begins with confronting our own awkwardness and a determination not to indulge in self-serving rationalizations that permit us to stay away. It is not easy to find something to say that does not offend sick people. Illness narratives often include an advisory litany of what to do and not do when dealing with the ill or with the family of the afflicted, but it is sufficient to show that you care. Don’t risk clichés and never insincerity. Words that are kind or not unkind often suffice, but words are not essential. ‘I don’t know what to say’ is the honest thing to say. Being there is good enough.

Stigma of illness is reflected in the reaction of the support players. Stigma depends on whether the ill are judged as being different because of their illness or whether they are accepted for the entirety of their being. Accepting illness as part of the human condition is a difficult lesson to learn. Not until Robert McCrum had survived a devastating stroke did he realize that he had previously been “indifferent . . . and frightened of illness” but then concluded: “Illness is OK. There’s nothing wrong with infirmity. It’s part of the way we are.”5 Accepting this is how to behave with the ill.

References

- Heaney S. Miracle. In: The Human Chain, Heaney S. London: Faber and Faber 2010

- Horton R. Why graduate medical schools make sense. Lancet 1998;351:826-8.

- Darling J. How to behave with the ill. In: The Poetry Cure, edited by Darling J and Fuller C. Newcastle: Bloodaxepoetry series, 3, 2005.

- Bennett A. An average rock bun. p599, In: Untold stories, Bennett A. London: Faber and Faber, 2005.

- McCrum R. My Year Off. Rediscovering Life after a Stroke. London: Picador. 1998.

- The King’s Speech (film) 2010.

- Hitchens C. Mortality. London: Atlantic Books, 2012

- Broyard A. Intoxicated by my Illness. New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1992.

- O’Driscoll D. Stepping Stones. Interviews with Seamus Heaney. London: Faber and Faber, 2008

- Spiro HM. When doctors get sick. Perspectives Biol Med 1987;31:117-33.

- Aoun H. From the eye of the storm, with the eyes of a physician. Ann Intern Med 1992;16:335-38.

- Rabin D, Rabin PL, Rabin R. Isolation from my fellow physicians. N Engl J Med 1982;307:506-09.

- Goffman E. Notes on the management of spoiled identity. London: Penguin 1990.

FERGUS SHANAHAN, MD, DSc, is professor and chair of the department of medicine, University College Cork, National University of Ireland, and director of the APC Microbiome Institute, a research centre funded in part by Science Foundation Ireland and by industry that investigates host-microbe interactions in the gut. His interests include most things that affect the human experience. He has published over 500 scientific articles and several books in the areas of mucosal immunology, inflammatory bowel disease, and the microbiota and including several articles relating to the medical humanities.

Spring 2017 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply