Sally Metzler

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

|

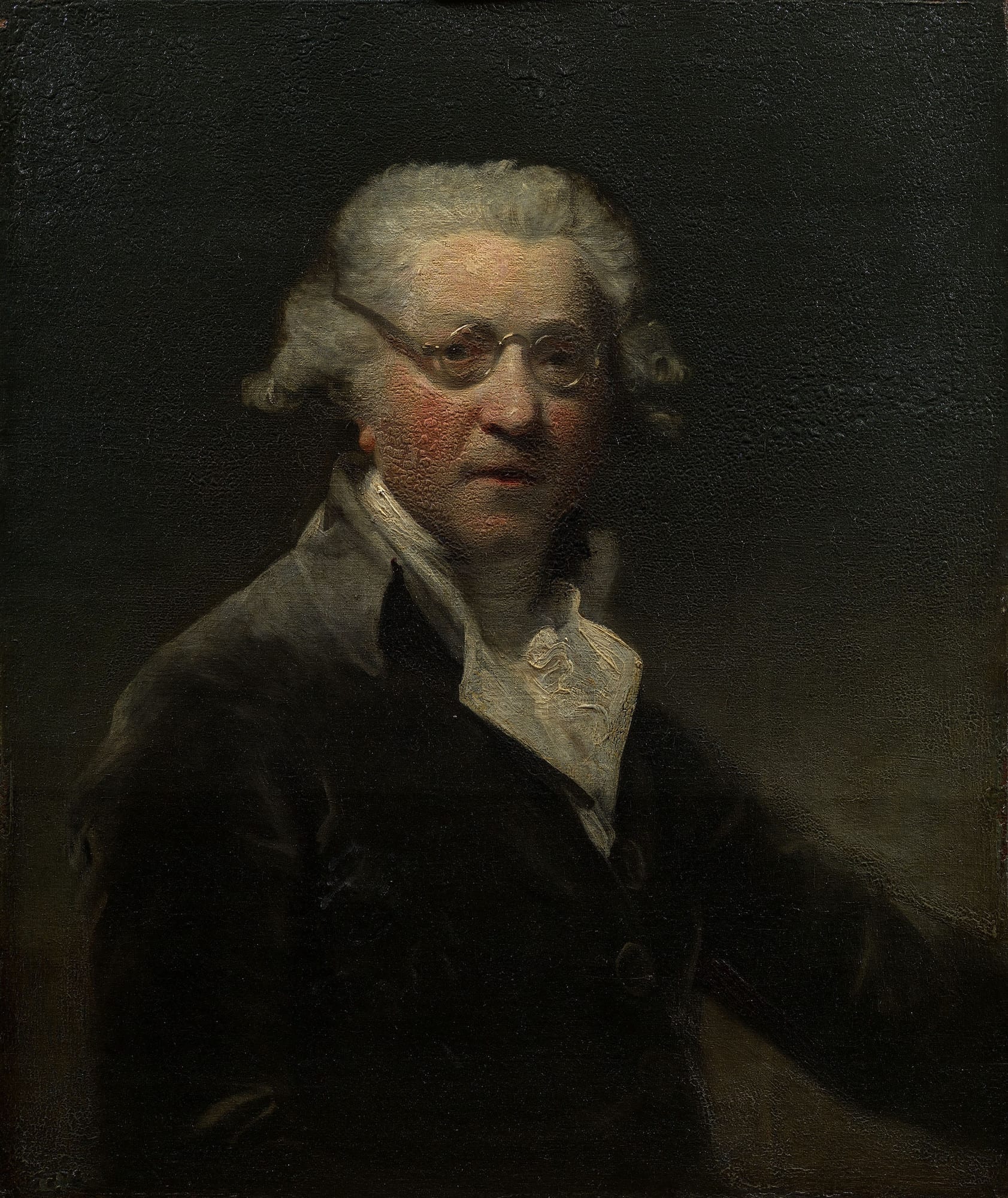

| Fig 1. Joshua Reynolds, Self Portrait, 1788, Royal Collection Trust, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. |

The subject of this portrait wears wiry, diminutive round spectacles, lending a distinctly pedantic flair. Yet gazing out is none other than Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), one of the greatest English painters in history (fig. 1). Sir Joshua headed the Royal Academy of Painters for twenty-four years, and wielded enormous influence on several generations of artists such as George Romney and Henry Raeburn. He was what would be known today as “portraitist to the stars,” immortalizing English society in elegance and grandeur. Reynolds’ knack for heightening the status and beauty of his sitter was unparalleled. Only his contemporary Thomas Gainsborough could compete.

|

|

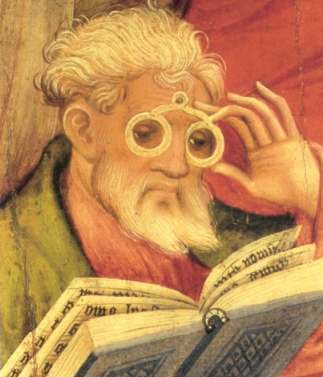

| Fig. 2. Conrad von Soest, detail, the “Glasses Apostle,” 1403, altarpiece of the church of Bad Wildungen, Germany. |

This painting, his penultimate self-portrait, calls attention for its grace and delicately calibrated palette of greys and browns. Even more striking are the wire-rimmed glasses Reynolds unabashedly sports. At the time of the portrait, he was sixty-five years old, a time in life at which many require glasses. Taking a long view, nothing much has changed in the field of ophthalmology and optometry. Medicine has indeed added to the spectrum of solutions and cures for eye maladies—namely cataracts and glaucoma, now can be treated with success. But the most common affliction of deteriorating vision continues to be treated in essence the same as in the day of Reynolds—229 years ago—by wearing glasses! Yet what has changed is the type of eyewear: Reynolds wears “wig spectacles,” fashioned with extra-long arms in order to wrap around the powdered wig. Men wore wigs certainly as part of current fashion, and it has been speculated as the result of head lice. Physicians recommended many remedies for head lice, such as the seeds of Stavesacre and Henbane,1 but a reliable cure was thought to be shaving the head completely, thus a wig would be worn out of necessity and vanity.

The precise date for the invention of eyeglasses is unknown, though most scholars agree it was in Italy towards the last half of the thirteenth century. Several works of art bear witness to the early presence of eyeglasses in some form, such as the bespectacled Apostle in Conrad von Soest’s altarpiece from 1403 (fig. 2).2 And in 1590, Jacob Stradanus made an engraving series depicting the “Nova Reperta,” (New Discoveries), among them were spectacles. By the time of Reynolds, glasses were more commonplace. Clearly, failing eyesight was the scourge for an artist, and cut short the career of many before the modern advances in eyewear technology. Reynolds suffered from poor vision, as the wig spectacles attest, but what is not clear is the health of his scalp. It will remain a mystery if his powdered wig was a fashion statement, head-lice disguise, or perhaps both?

End Notes

- See p. 543 in John Hill, MD: A history of the materia medica: containing descriptions of all the .., 1751.

- “Glasses Apostle” is considered the oldest depiction of eyeglasses north of the Alps.

SALLY METZLER, PhD, is the director of the art collection at the Union League Club in Chicago.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 1 – Winter 2018

Winter 2017 | Sections | Art Flashes

Leave a Reply