Mahala Yates Stripling

Fort Worth, Texas, United States

Library at Yale University

Arriving early as usual, Richard Selzer leaned on his cane near the High Street entrance to the Sterling Memorial Library. Now at 5’ 7” and 123 pounds, this world-famous doctor-writer looked diminutive, dressed in his tan corduroy pants and checkered shirt. Several people crowded around to greet him, and he politely feigned recognition. Selzer’s declining health has made him increasingly impatient, his status as a highly recognizable personage in the Yale-New Haven community becoming progressively more difficult with time.

After greeting like old friends, we took a nearby elevator down to the Bass Library, located under the verdant walking paths of Yale’s Cross Campus. He led me through a maze of empty workspaces to a narrow dimly-lit hallway where a modest table and two small chairs abutted the wall. Settling into our seats for our thirteenth interview, we discussed Diary,2 his fourteenth and final book. After having passed through the hands of four generations of editors/compilers over a dozen years, the voluminous manuscripts of the so-called diary book were dropped back into Selzer’s lap. Advancing in age and experiencing mounting difficulties with organization, he finished it himself. The final product is a treasure-trove that gives real insight into Selzer’s personal life.

As we spoke, friendly passersby—mostly janitors, librarians, and staffers—occasionally interrupted with “Hi, Doc,” which Selzer acknowledged with a faint wave of his hand. “They all know me,” he said, apologetic for the interruption. The library became Selzer’s refuge nearly thirty years ago when he left surgery to write. While a few events marked his social calendar over these decades—joining with nine other Yale literati for a weekly lunch with the Boys Friendly at Mory’s3 and becoming the Chairman of the Board at the Elizabethan Club4—a 1991 bout with Legionnaire’s disease led to escalating problems. Pneumonia or falls on the ice brought annual hospitalizations, and a bird watching trip with his two sons in East Rock Park became a tag-along event due to failing eyesight—further hampered by the need to relieve the symptoms of an aging prostate.

In the library these days, he often naps, and then, perhaps out of habit, arises fully awake as if called to surgical duty. Richard Selzer’s writing career has ended as well, his having left it, as he did surgery, “with no regrets.” As his memory increasingly grasped at words, he became progressively frustrated with the process. “I’d think about a word and fall asleep. Suddenly, in the middle of the night, I’d wake up, and there was an angel holding out the word I wanted on a silver tray. And I’d write it down quickly and go back to sleep.” Gone are the creative bursts resulting in works like his best-selling memoir, Down from Troy,5 taken as gospel by readers for its stark portrayal of a hardscrabble life. But he admits, “The minute I picked up the pen and began, the storyteller in me took over, and I was writing, not so much what happened—the facts—but I was reinventing my life as a story. It’s a blend of fact and fiction. It cannot be otherwise for a creative writer. It is no use for the reader to ask: ‘How much of that is what really happened?’ The probable answer is: ‘Not much.’”

He has been more prolific than his oeuvre of fourteen books in world-wide translation would indicate. His legacy includes hundreds of journal pieces and even more unpublished work in the Selzer Archive.6 Today he writes only to his journal, an intimate companion whom he addresses as “You.” He ran out of energy after painstakingly assembling an anthology of new pieces and diary entries and had to shelve the project. “Between you and me,” he confessed wearily, “I would like to lie down and turn my face to the wall.” His chronic fatigue is only broken by a postprandial glass of red wine.

Buried in the anthology are his last three stories, showing that inspiration for art can be anywhere. “The Flirtation” revisits a chivalrous act towards a middle-aged woman in a thunderstorm: “I went up to her, took her arm, and held the umbrella over her. She looked up—she was surprised. We walked several blocks to her destination, chatted, but didn’t exchange names. I enjoyed the experience thoroughly, and I know she did because of the little smile she gave me at the end.”

“Mister Stitches,” an autobiographical story emerging from a thousand pages of notes, troubles him still. Selzer, the author, is the title character, a surgeon who withdrew from surgery and became a tailor, another profession that cuts and stitches. Writing without self-awareness, Selzer recognized himself as Mister Stitches only late in the process: “I had to separate myself from the story to avoid literary suicide. There’s a deeply placed reason for this, but I don’t want to probe into my own psyche.” Continuing to tinker with “Mister Stitches,” he has discovered the difficulty of final good-byes to both of his arts.

Surprising things come from Selzer all the time, and the third piece, “The Last Grand Rounds of Richard Selzer,” is a case in point. In his own words:

Only a few years ago (twenty-two years after retiring from surgery)—I never go back to the medical school—the new Chairman of the Department of Surgery invited me to do a Grand Rounds. He had heard about the one that packed the house. So I said I would. I planned to have it be a reenactment of the dissection of a cadaver, which is the primary experience of an incoming medical student. They each have to take part in the dissection of a human body, and I decided to do it as a performance. I would play the cadaver—because I look like a cadaver—and I would have two students as attendants prepare the body for dissection. And I reserve the right to speak, to teach, and to address the audience even though I’m a cadaver. The piece ends up being a discussion about the differences between nakedness and nudity, because the cadaver has to be naked, vulnerable, and at the mercy of other people. The cadaver cannot be clothed. That would be absurd.

And so in the Grand Rounds I instructed the assistants to remove my clothing. So it becomes a discussion defining nakedness and nudity. Our patients are naked; they’re vulnerable and sick. The cadaver is naked. But nudity, as our Renaissance sculptors posed it, always has an element of the erotic. The naked body is something beautiful. As you probably read in my piece, “The Discus Thrower,” that’s taught all over, I compare the amputee patient of mine with the beautiful naked sculpture, The Discus Thrower. It’s one of my most famous pieces—it’s only 3-4 pages long.

In the Grand Rounds, one of the faculty members in the audience calls out, “Have you no shame to expose yourself before your students and colleagues in the nude?” “You are mistaken,” I reply. “I am not in the nude. I am naked . . . as a cadaver must be.” And I lecture, comparing nakedness and nudity.

It has become a famous event. I haven’t published it. I’m hoping to include it in the new anthology, just as I have told it to you. I think it would be very effective. Also very daring. I’m 83 years old, and I can do whatever I want. 7, 8

Returning home, I played back the recording. Caught up in the narrative of such a masterful storyteller, I shot an email to Selzer and asked, “Did it really happen?” His cryptic response:

Almost. If some detail of it is not factual, it is all the truth. I have indeed presented this “Last Grand Rounds.” (A word to my dear biographer: Your subject is a storyteller, one who rummages in his imagination and uses whatever detritus he stumbles upon to fashion his art. To insist upon what is and what may not be factual would, I think, not portray the man himself as he really is.)

That is, whatever Selzer dreams or imagines—his secret and private ruminations—becomes as real as everything else in his life. It makes a biographer’s task challenging.

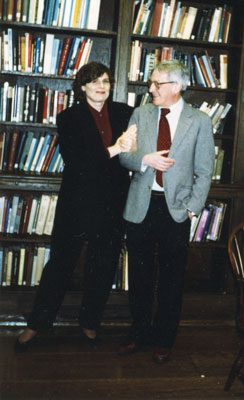

Mahala Yates Stripling, 1998

Asked if last words are important, Selzer responded: “Yes, as a kind of summing-up and a final sigh, a burst of the heart.” He wrote “Atrium,”9 a semi-autobiographical story of the conversation between an old doctor and a dying boy, which embodies this and expresses his feelings on death. “It just came,” he said of the creative process, explaining that he drew from “the three I’s”—instinct, intuition, and imagination—to write:

It was an intuition. In my story of a boy’s final wishes, he asks me, the old doctor who is sitting in the hospital atrium with him, “What would you do on your last day?” And it was his last day, and he was asking me. So I told him, and that’s of course what he wanted. He said, “Put me there in the forest.” And when I was leaving him there, I said, “I’d rather stay with you.” He said, “No, no. You can’t stay with me. You can wait in the truck, but promise not to come back tonight. When you come in the morning, if I’m still here, cover me with leaves so that I will not be cold. But if I’m not here, I will become a part of the forest.”

The reader experiences the doctor’s real grief in “Atrium,” but, Selzer says, “There’s a strong suggestion of a triumph over death, in that the boy will become part of the forest and continue existing in a different form. That is what I like to do in my writing: I eternalize events. I lift them right up out of this world, raising everything up out of mortality, so it has a meaning beyond this life.” His oft-expressed nonbelief draws the ire of some readers, but paradoxically, he avers: “At the confluence of my atheism and a strong undercurrent of religiosity there’s the hint of the eternal just beneath the story.”

“Atrium,” performed before an SRO audience, was one of Selzer’s last public readings. The attention bothered him: “There wasn’t a dry eye in the auditorium, and the standing ovation wouldn’t stop. And I thought, ‘I cannot do this again.’ But I walked to the edge of the stage and acknowledged it—with difficulty—because I’m a shy person, basically, not in my writing, but in my life I am.” He enjoys mail from readers but finds the limelight harsh.

Narrowing his eyes to look thoughtfully at me, Selzer said he wanted to tell me something. “Writing is different from living. It’s sort of the twin brother in my case, but because I plotted it all out, I didn’t make all the blunders I did in life. It’s art.” Cocooning himself in solitude and writing in silence, he saw only stories and characters. “Literature became my reality. My books are myself. There is no other me. Writing robbed me of a world of human beings,” and he often wonders: was it a fair trade?

People say to me, “Everyone envies you—your body of work will last one hundred years.” But, oh, my God, they haven’t any idea. That’s just writing. It’s not living. I’ve paid a price for making art that will endure. Everywhere I go, I have to be Richard Selzer. Don’t envy me. In my next life, I would write under a pen name. The things most men strive for—fame, money, sex, and gourmet food (just look at me—you can see it is not one of my major indulgences)—I don’t have any interest in. My mind is elsewhere. That’s what the true artist is. But now I’m at the end of it—83, that’s an old man. I’ll just sit back and daydream.

Richard Selzer is unsentimental about death, seeing it as a metabolic process: “We all stop.” Being a surgeon and writer taught him about life and death, and their combined power saved him for what was to be his destiny. “Otherwise, I would have had an early death, after a short and unhappy life.” His sense of wonder and awe at the universe is intact, and his spirit remains strong. The faith he lost as a child, he “misses terribly.” Even if he does not believe in heaven or any recognizable afterlife, he maintains a strong religious sensibility: “I call myself an atheist, but I’m more Christian than most of those who kneel and pray.” As a surgeon he gazed upon the body and saw the soul, expressed famously as “The flesh is the spirit thickened.”10 That is his version of the soul, which is a synonym for the spirit. His readers are attracted to this uniquely poetic philosophy stated honestly.

More than an hour had elapsed, and Selzer was tired. We rose from the table and stepped into the hallway and hugged, as usual, and I said, “Thank you for your time, Dick,” to which he replied: “My pleasure—really.” Then he said something I didn’t expect: “Mahala, this is probably the last time we’ll meet.” I asked for another hug, after which I said “thank you” and watched him walk down the long hallway, cane in hand, and out of the library, leaving me to collect my interview materials for perhaps the last time.

Biographer’s postscript: Richard Selzer recovered from his illness of a year ago, celebrating his 84th birthday on June 24, 2012. He finished “Mister Stitches.”

Notes

- All Richard Selzer quotations excerpted in this article have been drawn from a June 2, 2011 interview and related correspondence, as noted within the text.

- From Yale UP, 2011

- The Boys Friendly, an elite social club made up of mostly Yale Humanities emeriti professors, like the late Maynard Mack, invited Selzer to join them for their weekly Monday meeting at Mory’s, an old eating establishment filled with Yale memorabilia. They sit at a table for ten, so someone has to die before another person is asked to join.

- The Elizabethan Club, housing 16th & 17th-century books, is a social club of literati.

- From William Morrow, 1992

- The Richard A. Selzer Archive, est. 1998

- Basic transcription of audio from the June 2, 2011, Selzer-Stripling interview:

- See Richard Selzer. “Four Appointments with the Discus Thrower.” The Doctor Stories. New York: Picador, 1998. 227-30. Print.

- See Richard Selzer. “Atrium: October 2001.” The Whistlers’ Room. Washington, D.C.: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2004. 245-55. Print

- See Richard Selzer. “Textbook.” Letters to a Young Doctor. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Brace & Company. 13-20. Print.

Related Articles

Richard Selzer on writing

Timelessness of the intangible

MAHALA YATES STRIPLING, a Yaddo fellow, is an independent scholar who lives in Fort Worth, Texas. Her publications include Bioethics and Medical Issues in Literature (Greenwood P 2005), a medical humanities textbook used worldwide, and articles appearing in Teaching American Literature, Medical Humanities Review, and The Journal of Medical Humanities. She has lectured at Yale Medical School, the University of Texas Medical Branch-Galveston, and in the Great Hall of the Athenaeum on Nantucket Island. She is writing The Surgeon Storyteller, a literary biography of Richard Selzer, MD, in two parts: “Reinventing his Life” and “Living by his Wits Alone.” Visit her website, Medical Humanities, for information about the Selzer biography as well as Dr. Stripling’s other publications and lectures.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Summer 2012 – Volume 4, Issue 3

Leave a Reply