Annabelle Slingerland

Robin Seeley

The Netherlands

|

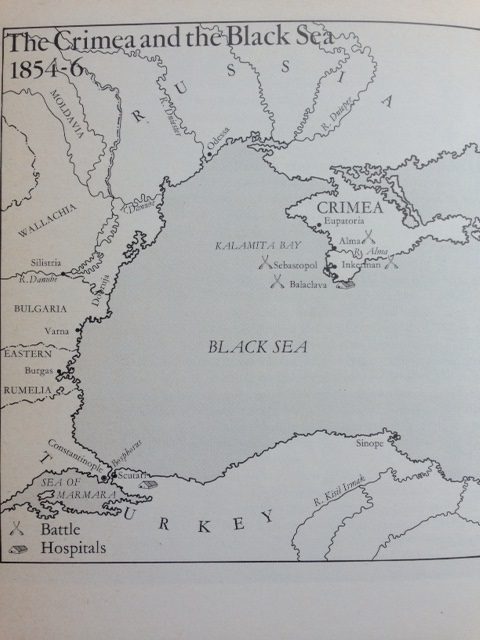

| Map of the battlefields and hospitals at the Crimea and Black Sea 1854-6, Manuel Lopez Parras |

|

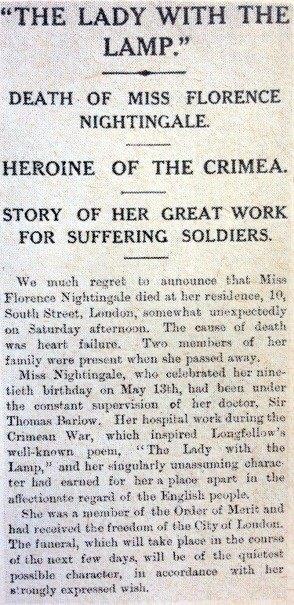

| 2a Death announcement in The Daily Graphic on 15 August 1910 referring to Florence Nightingale as the Lady with the Lamp in Longfellow’s poem |

While hospitals are often idealized as peaceful places, Scutari Hospital shatters all such dreams. It became notorious for bare battlefields, turbulent turmoil, traumatized soldiers, officers, governments. But its silver lining was nursing and scientific innovation that resulted in compassionate care with cutting edge technology.

Just beyond Crimea, the Black Sea emerges, flushing into the Bosphorus, a narrow twisting strait where near the Sea of Marmara the shadow of Scutari met my marathon swim. I needed to turn westwards to reach the peninsula of Istanbul on the European bank. That did not happen. As I headed west, huge waves lifted me up as if I were a pawn on a chessboard and dumped me down 100 yards to the south.

What is now Putin’s playground was once battleground for ‘the finest army that had ever left British shores.’ These brave Brits were malnourished and ailing as they fought on the fields of Sebastopol, Balaclava, Alma, and Inkerman before fleeing on hospital ships. The vessels were built to accommodate 250 patients, but forced to take on as many as 1500. Once the poor patients arrived at Scutari, the overcrowding did not get much better. The hospital’s long hallway was full of dirt and dust, with inmates packed along about 4.5 miles of beds spaced almost a foot apart. More often than not, their grave condition led to an untimely burial in the hospital cemetery. A grim ending indeed for many lives full of promise, far from British shores.

Welcome to Scutari, the Crimean War Hospital under Florence Nightingale’s administration that catapulted hospital design forward in an era when theories of miasma were mainstream. It was here that nursing emerged from its infancy, the military rapidly retooled, and statistics first held sway. In 1854, a supposedly invincible army faced down new enemies: diarrhea, dysentery, cholera. This took place amid severe supply shortages and woefully inadequate staffing.

|

| 2b Painting of the Lady with the lamp, GLC Photo Library |

The news reached Great Britain and appalled the public. At minister of war Sidney Herbert’s insistence, young Florence Nightingale, whom he knew had spent ten years secretly studying hospitals, took forty nurses on a mission to the Crimean. The goal was to confront Lord Stratford de Redcliffe Canning, the British ambassador in Constantinople, with her findings at Scutari. The ambassador was ostensibly in charge, although hardly master of the situation. The strait that separated him from Scutari’s mainland carried dead bodies and amputated extremities of the comrades at arms that he had half-heartedly tried to save. The British had lost Balaclava and won Inkermann, but that victory did nothing to help the victors weather the impending winter. That stormy season meant more sunken ships and lost provisions.

|

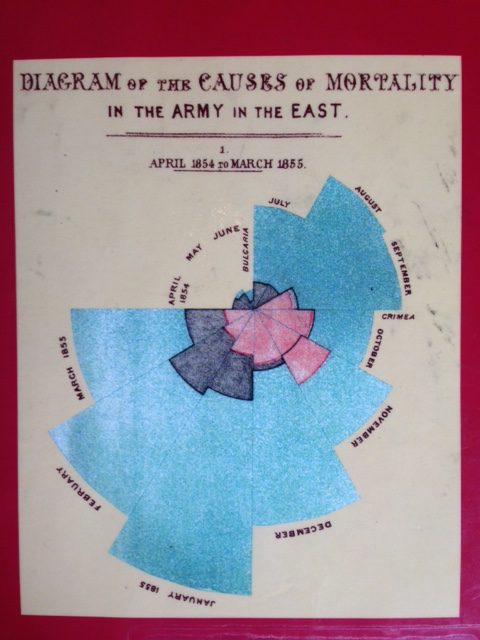

| 3a. Coxcomb diagram of the causes of mortality in the army in the east, April 1854 to march 1855 |

Nightingale’s reforms turned nursing, a previously undervalued “female” pursuit, into a true profession. The image changed from women who were ‘so kind, so duteous, diligent, so nurse like’ (Shakespeare’s Cymbeline), the empathic embodiment of the Lady with the Lamp to that of the Lady with a Hammer, breaking into storage bins to feed 12,000 starving soldiers in January 1855. She fought bravely behind the battle lines to improve hospital administration and supply lines and batter the British bureaucracy into submission. Although she even managed to finance reconstruction of a demolished hospital wing, she still could not make a dent in the escalating death rate. A “health committee” charged with addressing the Crimean Tragedy buried twenty-four different kinds of dead animals and removed 556 deletion chariots full of garbage. Her reports indicated that for every British soldier killed in battle during the Crimean conflict, seven more died from disease. Florence Nightingale’s urgently needed reforms included some of the administrative guidelines still used today.

|

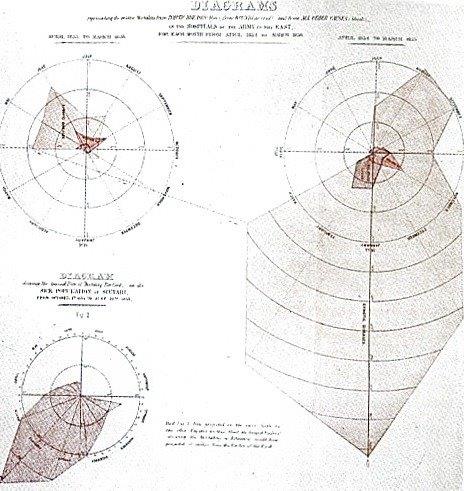

| 3b. Coxcomb diagram demonstrating Florence Nightingale’srigour in registration and use of statistics comparing death rates |

Farr, a British statistician studying French hospitals, focused on ‘zymotic’ factors, i.e. disease particles spreading through air and water, instead of ‘contagionist’ factors, which require direct contact.4 He welcomed the Crimean Challenge. By scrutinizing the statistics, he determined that overcrowding was the culprit. Poor hygiene trumped starvation, exhaustion, and medical mishaps as the leading cause of death. His theories came to the attention of a lady who had influence, Ms. Nightingale. Queen Victoria even invited her to consult on the plight of her husband, Prince Albert, who was suffering from typhoid fever.4 Unfortunately for the prince regent, insight arrived too late. Even his diligent doctors were oblivious of how the sewage system in Windsor Castle was the most likely source of his illness.4

While attempting to swim against the current in Scutari’s shadow, I had the good fortune to be swept into the arms of a sailor who shouted, “I have to take you out, now!” My lucky rescue at Scutari’s feet from the forces of nature led me to appreciate how capricious and deadly she can be.

Scutari Hospital’s harsh stumbling blocks in its brief two years of operation turned out to be an incubator of rapid developments for innovation in hospital administration, nursing, palliative care 13, treating soldiers as human beings instead of cannon fodder, 3,4,12 and understanding air- and waterborne disease transmission. The suffering of soldiers and Nightingale’s determination and persistence have proven pivotal stepping stones up till today.

|

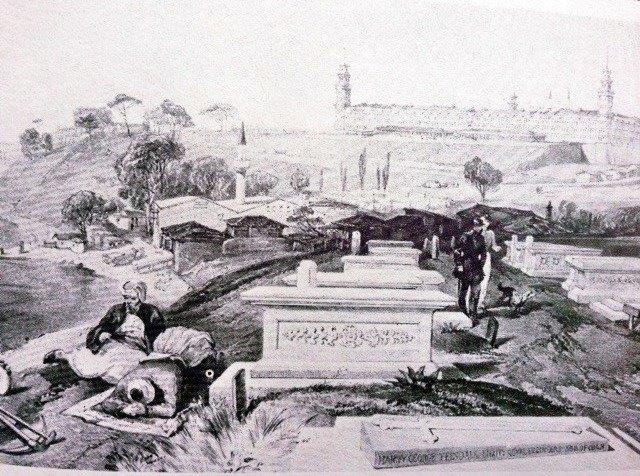

| 3b. Cemetry in front of Scutari War Hospital, drawing by William Simpson, National Army Museum |

Scutari’s hospital and cliff, the Black Sea, the Bosphorus, and Sea of Marmara can still be viewed from Top Kapi Palace. A ferry from the Galata Bridge can still transport visitors to the rebuilt landing pier in the present-day Uskudar, which is as least as densely populated as the former Scutari hospital. It is still a military place where one stumbles just as the soldiers in Jerry Barrett’s painting, the Mission of Mercy at Scutari.6 A little museum on Florence Nightingale can be visited on request. The cemetery will share tales of the 5,000 innocent souls who remain.

In memory of Don Conningham-Rolls

References

- Garrison FH, Notes on the history of military medicine, (Association of Military Surgeons, Washington DC, 1922). Corrie Derks, Mary Seacole’savonturen in de West en in de Krim, (Nijmegen, NL: Integraaal, 2007).

- Hugh Small, Florence Nightingale Avenging Angel, (London, GB: Constable and Company Limited, 1998).

- Royle T. Crimea: the great Crimean War, 1854-1856. New York: Saint Martin’s Press; 2000.

- Pam Brown, The rough British campaigner who was the founder of modern nursing (People who have helped the world), (Watford, UK: Exley Publications Ltd, 1988).

- Duberly FI, Journal kept during the Russian war: from the departure of the army from England in April 1854, to the fall of Sebastopol, (London, UK, Elibron Classics, 2000).

- Elsbeth Huxley, Florence Nightingale, (London, UK, Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1975).

- Gillian Gill, Nightingales, (New York, USA, Balantine Books, 2004).

- Shepherd J, The Crimean doctors: a history of the British medical services in the Crimean War. Vol 2. (Liverpool, UK, Liverpool University Press: 1991).

- Nightingale F, A contribution to the sanitary history fo the British army during the late war with Russia, (London, UK, Harrison and Sons, 1859).

- Nightingale F, Notes on nursing: what it is and what it is not, (London, UK, Harrison and Sons, 1860).

- Kubler-Ross E, Wessler S, Avioli LV, on death and dying, (JAMA 1972;221:174-9).

- Lambert A, Badsey S, The war correspondents: the Crimean War, Stroud, UK, Alan Sutton Publishing, 1994).

ROBIN SEELEY is a criminal law specialist who translates legalese into plain language jury instructions for the Judicial Council of California. She met her co-author in 2013 while giving a walking tour of San Francisco’s Japan town as a volunteer for San Francisco City Guides. Dr. Slingerland’s visit to Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay inspired her to write an article about its hospital. She enlisted attorney Seeley’s services as editor. The two have been collaborating on articles about historic hospitals ever since.

ANNABELLE S. SLINGERLAND, MD, DSc, MPH, MScHSR co-authored scientific international articles on physiology, public health and cost-effectiveness. On her USA journey through rehabilitation centers, she was impressed by veterans and both their medical and military history as in similar articles at Hektoen International portraying Alcatraz, Craighlockheart, and Westerbork.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2017 – Volume 9, Issue 1

| Sections | Hospitals of Note

Leave a Reply