“It is all up with him, or I am much mistaken! Something very extraordinary must have taken place; he looks to me as if he were in imminent danger of serous apoplexy. The lower part of his face is composed enough, but the upper part is drawn and distorted. Then there is that peculiar look about the eyes that indicates an effusion of serum in the brain; they look as though they were covered with a film of fine dust, do you notice? I shall know more about it by tomorrow morning.”

***

At half-past eight the doctor arrived. He did not take a very hopeful view of the case, but thought that there was no immediate danger. Improvements and relapses might be expected, and the good man’s life and reason hung in the balance.

“It would be better for him to die at once,” the doctor said as he took leave.

***

The two young men went back to the room where the old man was lying. Eugene was startled at the change in Goriot’s face, so livid, distorted, and feeble . . . .” One moment, if he asks for something to drink, give him this,” said the house student, pointing to a large white jar. “If he begins to groan, and the belly feels hot and hard to the touch, you know what to do . . . If he should happen to grow much excited, and begin to talk a good deal and even to ramble in his talk, do not be alarmed. It would not be a bad symptom . . . Our doctor, my chum, or I will come and apply moxas. We had a great consultation this morning . . . A surgeon, a pupil of Gall’s came, and our house surgeon, and the head physician from the Hotel-Dieu. Those gentlemen considered that the symptoms were very unusual and interesting; the case must be carefully watched, for it throws a light on several obscure and rather important scientific problems. One of the authorities says that if there is more pressure of serum on one or other portion of the brain, it should affect his mental capacities in such and such directions. So if he should talk, notice very carefully what kind of ideas his mind seems to run on; whether memory, or penetration, or the reasoning faculties are exercised; whether sentiments or practical questions fill his thoughts; whether he makes forecasts or dwells on the past; in fact; you must be prepared to give an accurate report of him. It is quite likely that the extravasation fills the whole brain, in which case he will die in the imbecile state in which he is lying now. You cannot tell anything about these mysterious nervous diseases . . . very strange things have been known to happen; the brain sometimes partially recovers, and death is delayed. Or the congested matter may pass out of the brain altogether through channels which can only be determined by a post-mortem examination. There is an old man at the Hospital for Incurables, an imbecile patient, in his case the effusion has followed the direction of the spinal cord; he suffers horrid agonies, but he lives.”

***

“I say, Eugene, I have just seen our head surgeon at the hospital, and I ran all the way back here. If the old man shows any signs of reason, if he begins to talk, cover him with a mustard poultice from the neck to the base of the spine, and send round for us.”

***

“Oh! it is an interesting case from a scientific point of view,” said the medical student, with all the enthusiasm of a neophyte.

“So!” said Eugene. “Am I really the only one who cares for the poor old man for his own sake?”

“You would not have said so if you had seen me this morning,” returned Bianchon, who did not take offence at this speech. “Doctors who have seen a good deal of practice never see anything but the disease, but, my dear fellow, I can see the patient still.”

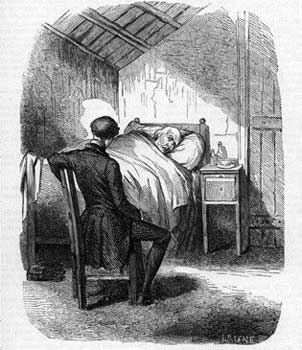

He went. Eugene was left alone with the old man, and with an apprehension of a crisis that set in, in fact, before very long.

***

His head fell back on the pillow, as if a sudden heavy blow had struck him down, but his hands groped feebly over the quilt, as if to find his daughters’ hair…. His voice died away. Just at that moment Bianchon came into the room . . . Then he looked at the patient, and raised the closed eyelids with his fingers. The two students saw how dead and lustreless the eyes beneath had grown.

“He will not get over this, I am sure,” said Bianchon. He felt the old man’s pulse, and laid a hand over his heart. “The machinery works still; more is the pity, in his state it would be better for him to die.”

***

They laid Father Goriot upon his wretched bed . . . Thenceforward there was no expression on his face, only the painful traces of the struggle between life and death that was going on in the machine; for that kind of cerebral consciousness that distinguishes between pleasure and pain in a human being was extinguished; it was only a question of time—and the mechanism itself would be destroyed.

“He will lie like this for several hours, and die so quietly at last, that we shall not know when he goes; there will be no rattle in the throat. The brain must be completely suffused.”

Freely abridged from Project Gutenberg Ebook of Father Goriot by Honoré de Balzac (1834-5)

Leave a Reply