A.J. Wright

Birmingham, Alabama, United States

(August 9, 1819 – July 15, 1868)

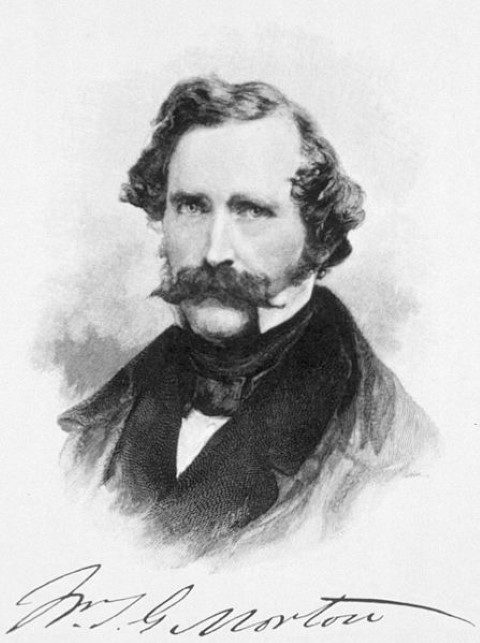

In medical history October 16 is known as “Ether Day” to commemorate dentist William Morton’s 1846 demonstration of ether inhalation for a surgical patient of Dr. John Collins Warren. The event is often described as the first public ether anesthetic because it took place before an audience of physicians and medical students in the operating theater of the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

As it so often happens with progress in science and medicine, earlier pieces of the surgical pain relief puzzle can be found. In England in 1800, near the very end of his massive book documenting research on the gas, Humphry Davy declared that nitrous oxide inhalation might be used to dull pain in some surgical operations. In the early 1840s Dr. Crawford Long in Georgia used ether for several operations, but did not publicize his work until later. Dentist William Clarke in New York also used ether in 1842. Another dentist in Connecticut, Horace Wells, used nitrous oxide in his practice in 1844, but an attempted demonstration in January 1845 was perceived as a failure.

Morton also used ether in his own practice before attempting the procedure on Dr. Warren’s patient, Gilbert Abbott. On the following day, a Saturday, Morton again used ether at the hospital to anesthetize a woman so that Dr. George Hayward could remove a large tumor from her arm. Then a lull of three weeks ensued. Morton called his substance “Letheon” and would not divulge its name. Because of its distinctive smell and their familiarity with ether from its longtime use in recreational “frolics,” many suspected the truth, and Morton was temporarily refused further access to the hospital.

Thus the benefit of surgical anesthesia to mankind briefly came to a halt. A rush of events in the following month sorted out the situation, and news of this medical technique spread rapidly around the world. On November 7, Hayward amputated a leg and removed a lower jaw under ether at the hospital. These were the third and fourth procedures at which Morton served as anesthetist. On the 9th Henry J. Bigelow, a junior surgeon who had witnessed the MGH surgeries, reported on them at a meeting of the Boston Society of Medical Improvement.

Three days later Morton and his mentor Charles T. Jackson filed letter patent number 4848, hoping to profit from the use of ether in surgical operations. Because of vociferous opposition from the medical and dental communities to such a patent, Jackson and Morton quickly made the true nature of their discovery known and freely available. Also on the 12th the first surgery in private practice under ether anesthesia took place in Boston. J. Mason Warren, son of John Collins Warren, was the surgeon.

On November 18 Bigelow published an account of Morton’s October administrations at MGH in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, launching the spread of ether anesthesia. Within a year the technique was in use in many countries around the world. Finally, on November 21 in a letter to Morton, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., suggested the word “anaesthesia” to describe the mental state produced by the inhalation of ether vapor.

Over the years medical historians have advanced many theories to explain the delay between Davy’s 1800 suggestion and Morton’s first public demonstration of surgical anesthesia. They ranged from an inability to make the intellectual leap to cultural forces surrounding the concept of pain. Yet the efforts of Davy, Long, Clarke, and Wells lacked one element that benefited Morton—a series of fortuitous events that quickly escalated into a storm of change.

Although Morton was a dentist, John Collins Warren—one of the best known surgeons in America—allowed him to experiment on one of his patients in his operating room at the prestigious Massachusetts General Hospital. Luckily Morton had already done some animal and human experiments. After two successful cases, the work stopped but resumed the following month. Bigelow quickly reported the first case at a local medical meeting and then published an article. Morton and Jackson released their secret. Ether anesthesia moved into private practice. Another prominent American physician gave the process a name. Without this fortuitous chain of events, surgical anesthesia might have been delayed even longer.

A.J. WRIGHT, MLS, has worked in the School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham since 1983. He has published numerous articles related to medical and/or Alabama history. In his spare time he is personal servant to three cats.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Spring 2016 – Volume 8, Issue 2

Leave a Reply