Elizabeth A. J. Scott

“Its tone was pure. The music enchanting.” So read the review of music played on Dr. Robert Knox’s violin for the visit of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons to Edinburgh in 1983. But if the instrument could speak as well as sing, what an amazing tale it would tell.

Robert Knox, the famous and then infamous anatomist of Edinburgh, was born on September 4, 1791. His parents had been tenant farmers of the Earl of Selkirk in Kirkcudbrightshire in the south-west of Scotland. They used to tell of the night in 1778 when, bidden to dinner by the Countess of Selkirk, the party was interrupted by Captain John Paul Jones, who sailed into the bay and ransacked the house of its valuables and silver—but in the most gentlemanly way, as even the Countess admitted. Jones was to return much of his booty eventually. But recognizing Knox’s mother as a friend of his childhood, for he too was from a farm in Kirkcudbright, he sent her in memory of that night a silver ladle. This she later bequeathed to her eighth child, Robert.

The family, however, decided to move east to Edinburgh. There Robert’s father became a teacher of mathematics in George Heriot’s Hospital, and young Robert was sent to the High School of Edinburgh. Classical school though it was, the High School was so over-subscribed that the senior Latin and Greek classes had as many as 200 children sitting in rows repeating words and phrases. Despite this and despite contracting smallpox which both disfigured his face and destroyed the sight in his left eye, Knox fought his way to become Dux of the school and a Gold Medalist.

He entered Edinburgh Medical Faculty in 1810 and likely learned to play the violin in his student years. It was at that time in Edinburgh a great social asset to be able to play an instrument. Knox bought a violin made by Johann Gottfried Hamm, a German master craftsman from Leipzig, who had moved to Rome to set up his atelier. Hamm was at the height of his career at this time. His violins were in the Italian style, beautifully crafted and often edged in ivory. Knox’s violin, now to be seen in Edinburgh’s Royal College of Surgeons’ Museum, still holds its warm Italianate tone.

At first unsuccessful in passing the University anatomy class examination, which had been taught by Professor Alexander Monro, an uninspiring teacher, he flourished under the internationally distinguished anatomist Dr. John Barclay who taught a much more popular extra-mural class and graduated in 1814. Unable to buy a practice but keen to use his training, Knox followed many contemporaries and accepted a commission as assistant surgeon in the Army. Posted immediately to Brussels, he found himself treating casualties from the battle of Waterloo. He then joined the 72nd Highland Regiment (Seaforth Highlanders) and sailed for South Africa where he saw service in the Fifth Kaffir War. His medical expertise was hugely enhanced in the field, but he also learned to shoot, to use a sword, and to ride well. It fascinated him that different African peoples had anatomical differences, and this sparked a lifelong interest in anthropology.

When Knox returned to Scotland, Dr. John Barclay offered to let him assist at his still enormously successful anatomy lectures. Knox had no hesitation in accepting. He left the army and took over more and more of his old tutor’s lectures, becoming as flamboyant and popular as Barclay. Knox was now well known in Edinburgh. He was welcomed at all social levels for his charm and ability to play the violin, as well as for his growing reputation as an anatomist. His younger brother Frederick John, who followed him into medicine, was now his assistant, and his prospects appeared to be boundless.

This was the time for him to settle down, marry, and take his place in society. As an up-and-coming anatomist and surgeon he could have looked high for a wife. Instead, however, he secretly married Mary Russell in 1824. His biographer, Dr. Henry Lonsdale (also one of his former students), says of the marriage, that Knox “inconsiderately put shackles to his social progress by marrying a person of inferior rank. As the son of a tenant farmer, he perhaps felt more comfortable with a wife of similar rank in society.”

Robert Knox was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1823. Thereafter, he was instrumental in setting up a new museum of comparative anatomy for the Royal College of Surgeons. He started with the valuable collection that Dr. John Barclay had developed throughout his career, which he then freely donated to the College. His only conditions for the gift were that it should be housed appropriately and that his name should remain associated with it. Knox drew up plans for this and was instrumental in adding to it the collection of Sir Charles Bell, surgeon to King George III. In 1825, Knox was formally appointed as curator of the new museum.

|

Surgeons Square, 1830 |

It was only then that Knox allowed the news of his marriage to leak out. He seems to have been well aware that in marrying Mary Russell he might have spoiled his chances of social advancement, and he kept the marriage secret until he had achieved his aspiration to be named curator.

Thereafter, invitations to the salons of the elite of Edinburgh dwindled. Imperious as usual, Knox, having chosen the lifestyle he wanted, reacted typically. He became even more flamboyant, arrogant, and unforgiving to his colleagues and competitors. At his well-attended extra-mural anatomy lectures, he wore a formal dark puce or black coat, with a high white or striped cravat caught by a diamond ring, all over a richly embroidered vest set off by watch seals and pendants. Black trousers and shining black boots completed the picture. His students adored him, but his colleagues throughout the Edinburgh medical hierarchy found him intolerant of any but his own views, and he began to make enemies.

But these were his glory years. Content with his wife, family, and violin, popular beyond measure as an anatomy lecturer, he poured out articles and treatises that impressed his fellow anatomists. At home, he was intensely happy and was well known as a warm, kindly host who enjoyed evenings playing music with his friends. Knox was by this time a good amateur violinist, and Schubert and Rossini were his favorite composers. While he had this domestic serenity, he brushed aside the growing antagonism of his rivals in the medical field. He basked in popular acclaim. It did not last.

Getting cadavers in a reasonable state for dissection was always difficult for anatomists at this time. The only legally available corpses were those of criminals condemned to death. “Resurrectionists” roamed graveyards to dig up recent burials and to sell the bodies to anatomy schools. The watch-houses, seen in most old Scottish graveyards, date from this time. They were usually simple two-story buildings, with one room on top of another, well served with windows, so that the bereaved could watch over their loved ones’ graves for a few days to make sure they were allowed to lie in peace.

In 1827, one of Knox’s assistants was pleased to pay £7 and 10 shillings for the corpse of an old pensioner who had died in the West Port lodging house of William Hare, an Irish immigrant laborer. Hare assured the assistant anatomist that the old man had died of natural causes and had no relatives. He was delighted to be paid for the corpse rather than have to pay for the burial himself. That night in the pub, he told the tale of this lucrative way of disposing of indigent lodgers to his friend, William Burke, another Irish immigrant working with Hare on the Union Canal. They both thought it was a splendid idea and began searching the back streets for vagrants dying by the roadside. As this was not productive, they began to murder aged homeless persons whose deaths would not excite interest.

Then, encouraged by better remuneration for younger bodies, they moved on to murdering prostitutes. They sold these bodies to Knox’s anatomy school. Some of them were recognized by the students and unease grew. The police became involved and the two men were charged with the murders. However the Lord Advocate was uneasy about a conviction for both, so he offered William Hare immunity from prosecution if he would turn State’s evidence. This he did. Burke was tried, condemned, executed, and his body given for dissection at the end of December 1829.

During the dissection, which was well attended, the spectators moved forward and there was a disturbance about the body. When this was settled it was found that much of the cadaver’s skin had disappeared. Weeks later, purses said to be made from Burke’s skin were being sold in Edinburgh (there is one in the College of Surgeons’ Museum).

Public execration followed the discovery of Burke and Hare’s activities. Knox, though exonerated from all complicity and not required to give evidence at the trial, was not spared. On one occasion, a crowd surrounded his house, howled insults, hung an effigy of him in full dress from a tree in front of the house, and then set the effigy alight. Despite police trying to disperse the crowd, they managed to break all the front windows by throwing stones at them.

|

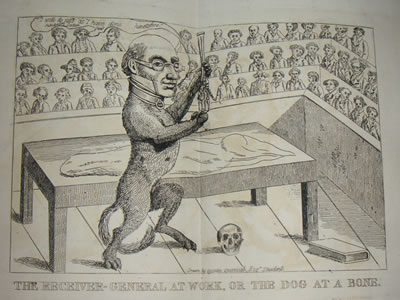

| “The Receiver-General at Work, or the Dog at a Bone” |

Over the next ten years, as the anatomy lecturers at the University became more competent, Knox’s extra-mural classes became less attended. He applied for other posts, but though well qualified for the positions, he never was offered them. He realized that Edinburgh had closed its ranks against him and poured out his bitterness against his colleagues in applications that merely confirmed them in their dislike of him.

This verse, circulating at the time, said it all:

Doon the close and up the stair

Butt and ben wi’ Burke and Hare

Burke’s the butcher, Hare the thief

And Knox the man who buys the beef.

Ever a fighter, Knox might have continued to struggle with the medical hierarchy. But when his wife died in 1841 after giving birth to a dead child, the bedrock of his inner contentment seemed to disappear. She must have created a very happy home for him. His friends were not so much his colleagues as men who played an instrument and could give themselves an evening of pleasure by making music together. Schubert’s silvery quartets and Rossini’s romantic music would have allowed Knox to forget his problems for an evening.

With Mary gone, Knox’s life disintegrated. He no longer cared about gaining position and reputation in Edinburgh. Did he feel guilt about fathering a birth that killed his beloved wife? We have no letters of that period to tell us. Did he feel he could go on? Clearly not! He resigned his position as curator of the museum that he loved and had been the pride of his life. It must have hurt him greatly when his letter was received without comment or thanks for his service to it.

In a symbolic gesture, he gave away his treasured violin, not to his museum but to a Mr. Fraser, a house factor in Bristo Street, who must have been a fellow violinist and steady friend throughout this unhappy time. He would never again enjoy the pleasure of playing music with friends. One hundred and thirty years later the violin was acquired from Fraser’s family for the Surgeons’ Museum.

Without his wife he could find no happiness in Edinburgh. Shortly after her death, he left for London to practice as a medical surgeon in Hackney. He remained in comfortable circumstances financially and was able to treat many of his less well off patients without a fee. Still much in demand as a lecturer, he was able to travel and keep himself active. He continued to write for medical journals, and eventually the Brompton Cancer Hospital offered him a position as pathologist. Here his students greatly valued his teaching and enormous experience.

Yet he remained a lonely, solitary man. There is no history of children being with him, and they may have died while he was still in Edinburgh, contributing to his grief. He himself died of a stroke on December 10, 1862, and was buried in Brookwood Cemetery near Woking. Now a stone inscribed “Robert Knox – Anatomist 1791-1862” marks his grave. It was set up in 1966 by the efforts of a contemporary curator of the Surgeons’ Museum, who had searched for and found his predecessor’s lonely unmarked grave.

A difficult, prickly man with enormous talent, Knox fought his way through life from school days onwards. Anatomists revere his expertise and cite his recognition of the ciliary muscle of the eye as a muscular structure and not a tendon as completely original work. His anthropological conclusions were less felicitous and even at the time had few supporters.

His work in setting up the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh was herculean and showed enormous knowledge and forethought. It remains the heart of the College and now, reorganized to tell the story of surgery and is open to the public, with Barclay’s and Bell’s collections still used for teaching and in examinations. However, Knox’s contempt for and arrogant disparagement of his colleagues and competitors in medicine served him badly. The sparkling wit enjoyed by his friends in his home was used with rapier like effect on his competitors in anatomy. What is clear is that while he had his wife to make his home life happy and his violin to bring joy to his mind, he did not care what his peers thought of him. Without them his peace of mind was at an end.

There will always be discussion about whether Knox, who always denied any knowledge of where his specimens came from, knew more about the origins of the Burke and Hare cadavers than he said he did.

His younger brother and former assistant, Frederick John, lingered in Edinburgh as a doctor for a few more years but then, apparently losing interest in medicine, took his wife Margaret and his large family and sailed for New Zealand. He set up the first library in Wellington, became its curator and a Burgess, and appears to have lived happily thereafter with his family around him. It was to honor his descendants in the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons that Knox’s violin was played in 1983.

is a retired general practitioner with a continuing interest in the problems of sleep and dreaming, who lives in Edinburgh, Scotland, not far from where Robert Knox lived.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Spring 2009- Volume 1, Issue 3

Spring 2009 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply