Megan Winkelman

Palo Alto, California, United States

“Our bodies conceptualize not only themselves but also each other, murmuring: Yes, you are there; yes, you are you; yes, you can love and be loved.”

–Nancy Mairs, in “Body in Trouble”

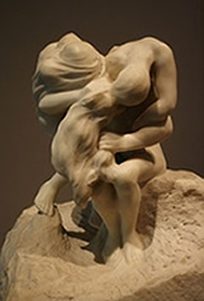

Auguste Rodin, Marble,

National Gallery of Art, DC

When I was four I lived in a blue house across from Ashby Flowers, a small glass shop guarded by a grey, stone cat. Each morning I walked past the busy street to visit her, stroke her, whisper to her, lie on the cement and curl into her. I believed if I just hoped long enough and loved strong enough, that cat would come to life, and she would be mine.

I am older now. I expect that some beings stay stone forever, unlike Adam, who continues to pour his sweet energy into the inanimate me. I wish I could stop him. “Listen, I know from experience,” a braver me would say.

He watches as I compulsively pick threads from the blanket at my knees, saving the cloth from asymmetry and myself from his gaze. My brothers used to press pieces of clear tape to their arms, only to strip the bits swiftly off their skin, giggling at the pain caused by something invisible. As I start the conversation, the memory crawls in my throat.

“The doctor gave me medication. An anti-depressant/anti-anxiety/anti-me pill.”

I laugh, as rehearsed. I want him to laugh too. He doesn’t.

“The psychiatrist spat out so many names, but don’t worry, I know his labels are like keys to a new world. Major depressive disorder sounds like a line in a poem. OCD could be a video game title. Dude, let’s go play some OCD.”

His cheeks dimple into tridents. I know he is wondering: will this recent development abort my midnight crying jags, and the phone calls that drag him out of bed to rebuild my laptop after I’ve disassembled the keyboard in search of imaginary dust? He stares, counting my eyelashes, never looking into my eyes. I don’t blame him. How can he climb through the window to my soul when all this clutter—the tears, the highs, the lows, the doctors, the talk therapy—crowds the sill? I pretend he is assigning one of my “incidents” to each lash: one, the arm-shaped crack in his bathroom wall; two, the nightmares vivid enough to change my waking landscape; three, the year my hips and pre-calculus erected insurmountable roadblocks to my precarious quest for perfection, and so on.

I want him to pass my test—this diagnosis and confession. Then I consider the alternative—his rejection laced with my justified rage—and I don’t dislike its taste. Actually, I revel in the scene’s absolutism, the way I would distill his leaving me into something pure. A rare moment of conviction, treasured with the same puritanical joy brought by separating food groups into individual corners on a plate.

Perhaps that, too, is the fault of the illness. In this way, the disease exonerates me. My neurotransmitters and hormones get together for tea without me to decide whether this day will be one of the bad ones…

Last summer, Adam and I visited the National Gallery in DC. We stood before Rodin’s sculpture The evil spirits. Three demonic figures curved over a naked woman, feeding off her fear. “Wow, babe, isn’t this beautiful?” His admiration drove the chisel further into my chest. Adam saw beauty in the figures that I wanted to crush like pigment in a mortar, finely ground down into something useful. My anguish writhed in stone before his eyes, and he saw art. Art!

How can I explain? I stop plucking the blanket and unleash the compulsive energy—not yet dulled by the drugs—onto my hangnails. I can’t explain. I haven’t been taught the words.

Adam doesn’t understand my illness, but foresees every bad spell. Like those elephants that predict tsunamis, he senses me changing even before I do. He isn’t as smart though—they flee to higher ground, while Adam stays by my side. Even on the bad days when I dream of forks scraping red railroads into my thighs, I think his pain surpasses mine. His pain metastasizes past the limits of reality, a tumor of the imagination, unconfined by the laws of biology.

In a robbery 15 years ago, a brick landed through the flower shop’s glass doors, smashing the cat—my stone confidante. I lost her magic in one night. It’s worse for Adam: he loses me in imperceptible increments. I worry, constantly, that he loves me only because he hasn’t yet learned how not to. I haven’t told him that even with the diagnostic labels I so adore, even with the new medical regimen, I am certain I will never be fully and consistently present in the way he deserves. I worry that he gently swallows my neuroticisms as he lets me blow my nose on his white shirt because he quietly believes that I will come to life; that I will someday become more than my demons, more than I am today.

References

- Mairs, Nancy. “Body in trouble.” Waist-high in the world: A life among the nondisabled. Boston: Beacon, 1996. Print.

MEGAN WINKELMAN is a junior at Stanford University majoring in Human Biology with a concentration in neurobiology, pursuing an honors thesis in feminist studies (class of 2013). Her mentor and professor, Dr. Larry Zaroff, inspired her to explore the human experience of illness through creative writing. This essay chronicles her struggle with depression, a source of both pain and insight.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2011 – Volume 3, Issue 3

Leave a Reply