“Success is not the key to happiness. Happiness is the key to success. If you love what you are doing, you will be successful.”

|

|

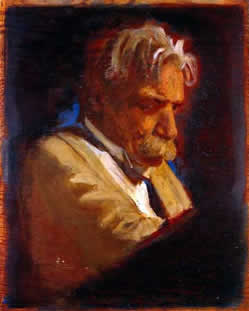

Albert Schweitzer |

In a different world Albert Schweitzer would have been a saint, painted by Uccello or Bellini with angels in the desert, shown pulling out a thorn from a lion’s paw or healing with his staff the dark-faced lepers lying on the ground. But Schweitzer was more versatile than that, and throughout his long life he continued to pursue a trinity of interests: music, philosophy, and theology.

Born in 1875 in a small village in Alsace, then part of the German Empire, he began his studies of music at an early age, and later studied the organ, playing it, writing about it, and restoring old organs to keep their rich sound. He published his studies of JS Bach in two volumes, befriended Richard Wagner, founded the Paris Bach Society, and addressed a world congress of music in 1905. In 1899 he obtained his doctorate in philosophy from the University of Strasbourg, writing his thesis on the philosophy of Kant. He became a deacon, a curate, a principal of a theological college. In 1900 he was awarded a theological degree magna cum laude from the University of Strasburg. In 1906 he wrote a book on the quest for the historical Jesus, later on St. Paul, and a history of civilization. He continued his studies on religion and ethics all his life; and over the next half-century developed his philosophy for which he became famous, based on reverence for all things living and service to his human fellow beings.

Already at the age of 21, in 1896, he had decided to live for science and art until he was thirty, then to dedicate his life to the service of humanity. True to his convictions, he resigned in 1905 from his position as principal of the theological college and enrolled in medical school. Graduating in 1911, he sailed from Bordeaux two years later with his wife, seventy cases of supplies and equipment, and 2000 marks of gold. Fifty miles below the equator, in the village of Lambaréné in Gabon, then part of French Equatorial Africa, he established his hospital. On the banks of the Ogowe River, an area was cleared of impenetrable jungle and tall mahogany trees to build his consulting rooms and hospital, first in an old fowl-house, later in log cabins, and eventually in buildings of corrugated iron. Some 500 patients from various tribes came to be treated each month. They would arrive with their families and all their possessions, including cooking utensils, sitting on the steps of the makeshift hospital, patiently waiting to be seen. They suffered from sleeping sickness, leprosy, malaria, elephantiasis. They needed surgery for tumors, syphilitic lesions, strangulated inguinal and umbilical hernias. As the compound around the hospital expanded and large bamboo huts were built for their accommodation, they grew bananas, guavas, and mangoes. They and their families received rations of fruit, palm oil, and manion—the source of tapioca. They ate fish and sometimes non-man-eating crocodile. With sewing machines, uniforms were made for the nurses, cloths for the patients, and a laundry was operated every day of the week.

On Sundays, Schweitzer would hold an open air service in French, his sermon translated sentence by sentence into native dialects. To be successful in Africa, he once told the visitor, one has to be a carpenter, a mechanic, a farmer, a boatman and trader, as well as a physician and surgeon. When he returned after being interned in France as an enemy citizen during World War One, he found that the hospital had been overgrown by the jungle and needed to be rebuilt again. It was gradually expanded, modernized, and as the years went by more doctors and nurses came to work there. By 1927, when he departed for Europe, he left behind a functioning hospital. With the exception of several trips to Europe and America, he worked in Lambaréné until 1948. He continued his writings and became widely known for his philosophy of reverence for life. With Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, and others, he campaigned against nuclear tests and nuclear weapons. During his long life he received many awards, including the Nobel Prize in 1952. He died in 1965 at his beloved hospital in Lambaréné. For his dedication to peace, service to his fellow men, his theory of reverence to all things alive, human animal and plant, and for his numerous writings on ethics he is indeed remembered as one of the saints of humanity.

References

- Eric Anderson and Eugene Exman. The World of Albert Schweitzer. Harper and Brother, 1955.

- Schweitzer, Albert. Out of my life and thought. A Mentor Book 1933.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Highlighted in Frontispiece Summer 2013 – Volume 5, Issue 3

Summer 2013 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply