Raymond Curry

Illinois, United States

|

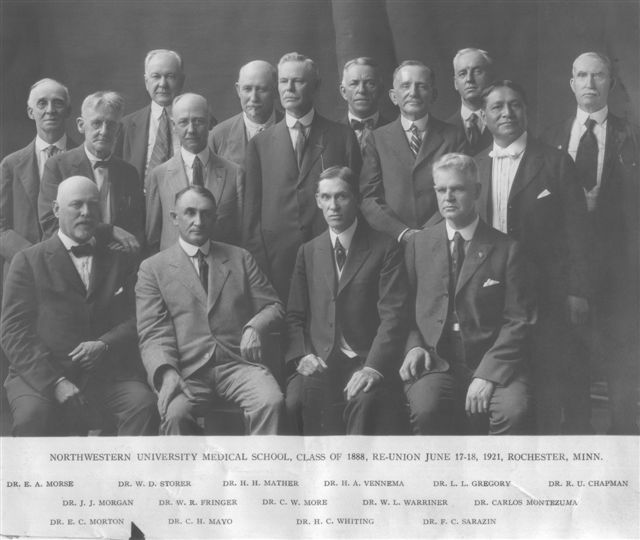

| Photograph of Carlos Montezuma (standing second row, far right) Northwestern University Medical School, Class of 1888 Reunion Rochester, Minnesota, June 17–18, 1921 |

Carlos Montezuma (1865?–1923) was a unique figure and a fascinating study in the construction of a meaningful and influential life astride two often conflicting cultures. He was one of the first two Native Americans to receive an MD degree (1889). Although most of his contributions were as an activist and writer, Montezuma stands alone as the first Native American physician of any importance. His story deserves much wider recognition and attention.

As detailed in Leon Speroff’s recent biography and other sources, he was born in 1865 or 1866 into the Yavapai tribe and given the name Wassaja—a “signal,” or “beacon.” His family fell victim to intertribal rivalries, and he was captured in a Pima raid on the Yavapai camp when five years old. About a week later he was sold by his captors to Carlo Gentile, a photographer turned gold prospector, who adopted him and christened him Carlos Montezuma. His next few years with his peripatetic adoptive father were extraordinary—at six he was an actor in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show—and thanks to Gentile’s profession a remarkable number of photographs of the young Montezuma survive. On their return to Chicago, where Gentile owned a studio, Montezuma began going to school, proving an inquisitive, sociable, and intellectually talented student. With the aid of a sponsor in the Baptist church he entered the University of Illinois at age fourteen, graduating from the pharmacy program, as president of his class, at eighteen.

According to the wishes and recommendation of his sponsor in Urbana, Montezuma was then admitted to the Chicago Medical College, now Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. The school did not charge him tuition. His classmates included Charles Mayo, later very helpful in facilitating political contacts, and Joseph B. DeLee, who was to become a leader in American obstetrics and gynecology. Whether because of discriminatory assessments of his professional development—Montezuma complained in a contemporary letter that “they have a prejudice[d] personal feeling towards me”—or because, as he later claimed, he needed to take time off to support himself through work in a downtown pharmacy, he took five rather than the usual four years to graduate, and received the MD degree in 1889.

After six years as a physician in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Montezuma returned to Chicago to practice medicine. Clinical medicine, however, does not seem to have been his forte. He focused on diseases of the gastrointestinal system, using various pills and salves, colonic lavage, and analysis of aspirated gastric contents. He maintained an office downtown, in the elegant Reliance Building (an early skyscraper, now beautifully restored), but saw most patients out of his home on the near south side.

He was much more influential as a social leader, and it is here that the historical context of Montezuma’s life and his influence becomes most interesting. For progressive social reformers at the turn of the Twentieth Century, Richard Henry Pratt and Jane Addams alike, assimilation was the watchword. In guiding the upward trajectory of immigrants and minorities, the potential virtues of a multicultural society, preserving the music, art, and stories of its cultures were largely sacrificed to showing potential assimilation into white society. Montezuma’s own education, his early work in the Indian Bureau, his devotion to Freemasonry, and his practice well within the mainstream of Chicago medicine were all consistent with these assimilationist views. Enter Gertrude Simmons, also known as Zitkala-Sa, with whom Montezuma had a brief but intense romantic and intellectual relationship in 1901. An accomplished writer and musician, deserving of more biographical attention in her own right, Zitkala-Sa was simultaneously moving away from her own assimilationist past to champion the preservation of tribal cultures. Their relationship foundered as a result but not without lasting impact on Montezuma’s thinking.

Montezuma’s own evolving views were complex and not easy to describe. His opposition to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, initially undertaken on the grounds that it inhibited opportunities for assimilation, was further fueled by his involvement in the Yavapai’s resistance to the Bureau’s abridgement of their land and water rights at the McDowell reservation in Arizona. It was at this point that he first presented his best-known tract, “Let My People Go,” to the Society of American Indians in 1915. His relative mobility and stature made him an extremely successful spokesman, and he became known in Washington as a troublemaker—far more effective than the uneducated and compliant constituency they imagined.

In advocating for the Yavapai, Montezuma moved beyond his earlier uni-dimensional opposition to the Indian Bureau, developing a new appreciation for tribal culture and an increasing identity as an Indian. From 1916 until his death in 1923 he published the monthly newsletter Wassaja (“Freedom’s signal for the Indian”), still advocating the abolition of the Bureau and protesting the wartime military draft of Indians, half of whom were still denied the right of US citizenship.

Montezuma’s journey led him progressively back to his Yavapai origins. Aware that he was dying of tuberculosis, he traveled to the McDowell reservation in December 1922, and established himself in a traditional oo-wah, where he died the next January. He is buried there, at the McDowell reservation—no small irony for a man who had insisted for so many years that he was “not a reservation Indian.”

References

- Speroff L. Carlos Montezuma, MD: A Yavapai American Hero.Portland, OR: Arnica Publishing, 2003.

- Iverson P. Carlos Montezuma and the Changing World of American Indians, University of New Mexico Press, 1982.

, MD, is senior associate dean for educational affairs at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, and clinical professor of medicine and medical education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. A native of Lexington, Kentucky, he is a graduate of the University of Kentucky and of Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, and completed internal medicine residency at Northwestern University/McGaw Medical Center. He previously (1998–2014) served as vice dean for education at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Spring 2017 – Volume 8, Issue 4

Spring 2015 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply