Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

|

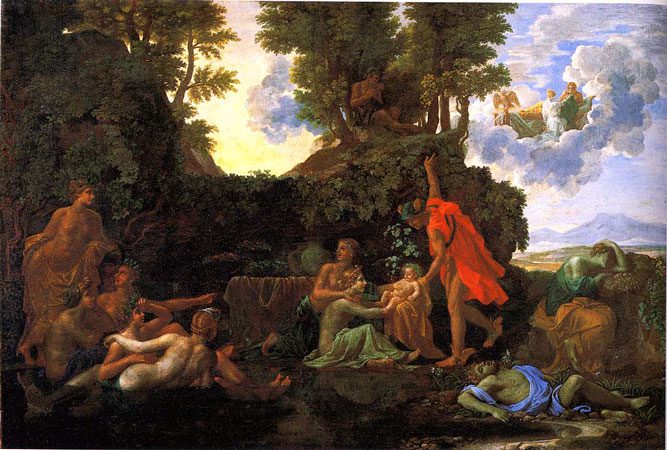

The birth of Bacchus, 1657 |

Two thirds of this canvas, depict a well-known story of Greek mythology told by Ovid in his Metamorphoses.1 Juno, queen of heaven and wife of Jupiter, is furious to discover that her husband had an affair with Semele, daughter of Cadmos. You would think that by now the goddess would have acquired some degree of tolerance to the sexual indiscretions of her spouse, whose philandering exceeded all measure, even by Olympian standards. Only the new case is different: Semele is with child; and this—to conceive a child by Jupiter and by him alone—is more than Juno could boast, and clearly more than she was prepared to endure. Therefore, the cheated goddess transforms herself into an old crone with the semblance of Semele’s former nurse, and so disguised cleverly works on her vanity to cause her perdition. She makes her doubt the importance of her adulterous liaison. What good is it to proclaim that she carries in her womb the child of a god—and the ruler of the whole godly cohort at that—when no one knows it, no one has seen him, and she herself has no proof of his identity? Many a man has won admittance to a woman’s bed merely by pretending to descend from a heavenly lineage.

Tormented by misgivings, Semele shrewdly exacts from her immortal lover the oath that he is to grant her one wish. Before he can stop her, Semele declares her desire: it is to see him in all the majesty of his divine persona, just as he would appear to Juno and to all the rest of the gods and goddesses in his Olympian abode. Since Jupiter has sworn most solemnly, he sees no recourse but to grant her wish. Alas, the direct sight of a god is unbearable to simple mortals. No human being can withstand the immediate perception of the awesome, overwhelming divine might. Semele is no exception. Jupiter appears before her, this time not in his assumed human form, but in that of his original divine self, and Semele, as if struck by a thunderbolt, falls to the ground, utterly calcinated.

|

|

Mercury – Detail |

Jupiter, although an incorrigible lecher, must have been a passable father. Or so it seems from his compassionate impulse to rescue his son, at the very last moment, from the flames that consumed Semele. He plucked the fetus from the burning womb and sewed it to his own thigh, where it continued to develop until term. Surgeons will wonder what procedure he used. Perhaps they should count Jupiter among their illustrious precursors, as the inventor of the surgical technique now called “marsupialization.” Hence originated the appellation of Bacchus as bis genitus, “the twice-born,” once from his mother’s womb and once from his father’s thigh.2

Poussin did not represent the actual birth of Bacchus, but the consignment of the infant god to the care of the nymphs, who reared him. The artist places the scene in front of a dark cave overgrown with ivy, luscious grapes (it is Bacchus, after all, who has arrived), and various fruits. In front of the cave, the seven nymphs have gathered by a pond. Mercury, attired in a flashy red mantle, has just come down from heaven, and proudly points to the empyrean with his right hand, while with his left he delivers the infant-god to the nymph, Dirce, who receives it. She is embraced at her shoulders by another nymph, who shows the infant to her admiring companions. Up in the clouds, on the right side, is Jupiter, recovering from his thigh-based parturition and being tended by Hebe, the goddess who was traditionally the cupbearer in the Olympian revels. Behind Mercury and the group of nymphs receiving the newly born, the god Pan sits on a hillock playing joyous melodies with his reed-flute in celebration of the arrival of Bacchus.

|

|

Narcissus – Detail |

On the lower right corner, the composition seems unbalanced by the presence of a young man lying on the ground, exanimate. He is Narcissus, grief-stricken at his inability to seize his own image, with which he is madly in love. He is about to die or may already be dead from despair. We recognize him by the white flowers—narcissuses—that blossom forth around him and the pond, in which he gazed at his own beloved, yet insubstantial image. Lastly, behind him, the woman sitting on a rock holding her head in a dolorous attitude of inexpressible suffering is Echo. She is in love with Narcissus and turning to stone upon contemplating his agony.

This painting has received numerous interpretations among scholars and art critics. They have wondered why Poussin decided to include two different, seemingly unrelated mythological stories in the same piece. There has been no satisfactory explanation. A priori there seems to be no coherent reason, either of symbolism or pictorial technique, for this inclusion. According to Giovanni Pietro Bellori,3 contemporary and friend of the painter, Poussin was simply illustrating Ovid’s text, since both narratives are found in Book Three of the Metamorphoses. However, this explanation has been considered “too lame,” not to mention the fact that in Ovid’s book the two stories do not succeed each other, but are separated by another narrative, that of Tiresias.

Experts often refer to the Greek writer Philostratus (ca. 170–205 CE), whose work Images (Eikones) is a collection of descriptions of paintings, some real and some imaginary, that strongly influenced many artists in succeeding centuries. Poussin was familiar with it. The chapter entitled “Semele” contains many elements reproduced in Poussin’s Birth of Bacchus, and is therefore proposed as an important source of the discussed work.

Scholars have resorted to abstract philosophical concepts to explain the iconology. Thus, it has been suggested that the nymph, Dirce, represents “matter,” and Bacchus “form [in the Aristotelian sense] being infused into matter.”4

A learned commentator saw in this painting more than just such formalist figurations as “the entry of a small boy into a moist grotto populated by seven half-naked surrogate mothers” while the father is absent and a contrasting scene of erotic love-death (Narcissus and Echo) enacted nearby. He saw a complex web of symbols alluding to the dramas of paternity, legitimacy, and desire. “Desire,” he wrote, “is as much of a theme as the opposition of death and rebirth.”5

In sum, Poussin’s The Birth of Bacchus is a work of art about which scholars have long engaged in a lively debate concerning the possible meaning behind the images. No doubt erudite researches will continue, without any one fully explaining what led the limner to conceive, dispose, and arrange his figures the way he did.

Lacking a formal training in esthetic theory or art interpretation, but looking at the painting from the vantage point of someone who spent his life in the medical world, I cannot but be fascinated at the artist’s cryptic impulse to juxtapose birth—or rebirth—and death so dramatically in the same canvas. On one side are warm colors of brown, red, and yellow; on the other, the cold feeling of the blue. There, life surges ahead; here, it painfully drags to extinction; and the two scenes appear side-by-side in a harmonious composition. It is as if the artist had fully understood this great truth: that life and death, contrary to what most people think, always coexist in a mutual, intimate connection.

All biologic life is essentially binary: compounded of vital and deadly elements inextricably joined to each other. This is true since our earliest beginnings. Metaphorically speaking, the fetus dies that the child might live; in plain matter of fact, wholesale death is constantly occurring in the living organism. During fetal development, a true hecatomb of cells and tissues must take place before the infant is fully formed (think, for instance, of kidney development: two complete excretory systems are successively produced and blighted before a third, the last one, is finally shaped). In brief, the artist somehow sensed that, in a strict sense, life and death are not opposites, but two aspects of one and the same thing, rather like the obverse and reverse of the same coin.

Notes

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, trans. Mary M. Innes (New York: Penguin Books, 1955).

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, trans. A. S. Kline (2000), Book III, verse 315. http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/Metamorph3.htm#_Toc64106188.

- Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Le Vite de’ pittori, scultori e architetti. (Rome, 1672), 445; and Dora Panofsky, “Narcissus and Echo: Notes on Poussin’s Birth of Bacchus in the Fogg Museum of Art,” The Art Bulletin 31, no. 2 (June 1949): 112–120. Bellori’s book exists in a 1976 edition printed in Turin.

- Sir Antony Blunt, “The Heroic and the Ideal Landscape in the Work of Nicolas Poussin,” Journal of the Warburg and Coutauld Institutes 7 (1944): 154–168.

- Richard T. Neer, “Poussin, Titian, and Tradition: The Birth of Bacchus and the Genealogy of Images,” Word and Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Inquiry 18, no. 2 (2002): 267–281.

FRANK GONZALEZ-CRUSSI, MD, is an emeritus professor of pathology at Northwestern University. Since 2001, he has retired from his post as head of laboratories at the Children’s Memorial Hospital of Chicago. He has written over 200 articles in peer-reviewed journals, briefly became chief editor of Pediatric Pathology, and authored two books on the pathology of specific types of pediatric tumors. In the literary field, he has written 16 books (five in his native Spanish), most in the essay genre. Translations of his work exist in 10 languages. Dr. Gonzalez-Crussi has been the recipient of numerous awards, including a Fellowship of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. His latest book is Carrying the Heart (Kaplan Publishers, New York, 2009).

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2012 – Volume 4, Issue 4

Fall 2012 | Sections | Birth, Pregnancy, & Obstetrics

Leave a Reply