Erika L. Lundgrin

Cleveland, Ohio, United States

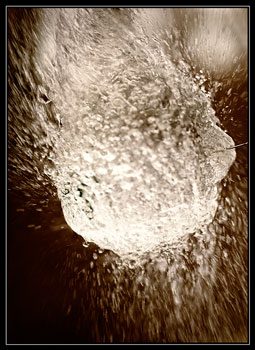

Photography by Fraser Catlin

A young girl is sitting in the room, pregnant, water broken, waiting. I know by a quick glance in her chart that we have no information about her in the system. A good history will provide all of the important details of her pregnancy: a small challenge, one I feel equipped to face. But the nurse who checked her in, took her vitals, and gave me a brief history ended with a whisper, “She’s a bit slow.” These words echo in my mind as my conversation with the patient progresses like a stone sinking in mire.

“What brings you in today?” I ask after introducing myself.

“I think my water broke.” I wait for her to elaborate, but she does not.

“What happened when you thought your water broke?”

“When I woke up I was all wet. So I called the ambulance.”

“I see. How far along are you in this pregnancy?”

She pauses. “What do you mean?”

“When is your baby due?”

She states a date that I jot down, counting on my fingers. That puts her at roughly thirty-one weeks gestation.

“What is your due date based on?”

Another pause. “What do you mean?”

“How did you find out your due date?”

“The doctor told me.”

“Ah, what doctor was that?”

“I don’t know.”

“When did you last see the doctor?”

“In January.”

It is late March. Her voice is tiny, timid, and she answers without haste, without inflection, and seemingly without anger, fear, or sadness . . . without comprehension.

Slowly, I discover that she has seen an obstetrician, once, a couple months ago. She has never had an ultrasound. She apparently missed visits with this same doctor and, in fact, never saw her again, because her auntie could not, or would not, take her. And now, after calling an ambulance, she is here in the labor-and-delivery triage with rupture of membranes at a not well-defined, but clearly preterm, gestational age. I remind myself to simplify my language to try to get the most accurate information. But I am no longer confident I am getting the whole picture.

“Do you have any medical problems?”

“No.”

But is it “no” because she truly does not have any? Or because she rarely sees a doctor and has never been diagnosed? Or because she does not know her medical history, or has no idea what I am asking? I list some, just in case. Diabetes? High blood pressure? Thyroid problems? Herpes? Seizures? Asthma?

To each, she says no. But I still am not sure what kind of “no” those “no’s” are.

“Do you take any medications?” Sometimes this helps.

“I was taking something, but I don’t know what it is.”

“Do you know what it was for?”

“A yeast infection.”

We circle on in this fashion awhile more until I have gathered the important information. She has denied contractions and does not appear to be in labor; that would make this a preterm premature rupture of membranes: PPROM. But it is not helpful to spout acronyms at her, and this evaluation simply begins with me. I tell the resident all I know, and we go back in together with the ultrasound machine.

Almost immediately, the resident calls in the attending because she cannot see lungs, there is fluid around the heart, and the skull is not quite round. After the attending scrutinizes the image of the fetus, which is so much more difficult to see without fluid in the womb, he begins to use words like “nonviable” and “bony dysgenesis.” The young woman’s face, as it has throughout my interview with her, remains blank, noncommittal. The fellow, who has joined us to also stare at the blurry black and white images, tries to translate. “Do you understand?” she says kindly, softly. “It looks like your baby probably will not make it.”

The girl does not answer for the longest time. But, at last, she says, “I’m just a little upset.”

I wonder how it got to this point, why this is happening to her. Could it have been prevented or detected earlier if she had received better care? And I wonder what it would have taken for her to get that care. She is poor, uneducated, living in a group home, and seemingly without much guidance from a responsible adult. It seems preposterous to say these things did not all play a role in some way. But did anyone impart to her at some point the importance of prenatal care, nutrition, or monitoring the movement of the baby? I wonder if she came away from her one obstetric visit with anything more than an estimated due date. And whether she will leave labor and delivery today with anything more than a broken heart over a lost pregnancy.

ERIKA L. LUNDGRIN is a fifth-year medical student at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University. Upon graduation next spring, she intends to pursue a combined residency in internal medicine and pediatrics. When not filling out residency applications, she enjoys reading, writing, and dancing. She plans to continue to use writing to reflect on her experiences as a health care provider and the challenges faced daily in medicine.

ighlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2012 – Volume 4, Issue 4

Leave a Reply