Andrea Marks

United Kingdom

Example of a stereoscopic photo11

Medical imaging has always been an important and valuable tool in the practice of medicine.14 Before the introduction of photography in the late nineteenth century, medical professionals used wax models, illustrations, and paintings to document clinical conditions and procedures.7,14 Photography has been used in the medical setting for over a century,1 and since its introduction, images have become an important part of a patient’s medical notes.2 The first known medical photograph was a Daguerreotype created in 1845 by Alfred Donne1,8 and thus began medical photography. The Daguerreotype process led to the creation of black and white photography.1 Black and white photos were often hand colored to show details not captured by the photos themselves.1 Black and white photos were used to create stereoscopic photos, which, when viewed through a stereoscope, produced three-dimensional images.1 In 1888, the first portable box camera was created and in 1914, the process of creating colour photos emerged.1 Over the years, this has progressed to the “digital image revolution” of today, which has dramatically changed the face of medical photography.1

Dermatology relies heavily on photography and imaging, as it is a very visually based specialty.14 In the mid-1800s, the ability to paint and illustrate skin conditions was considered a necessary skill for a dermatologist to create realistic images of the different skin conditions they encountered.7 In the mid-1800s, the University of Vienna hired two physicians as medical illustrators; their role was to paint life size watercolor of patients’ skin conditions.7 The introduction of black and white photography changed things significantly, however images were still limited in what they could convey as they had no color.7 When color photography emerged, the need for medical illustrators decreased significantly, as photographs were now able to effectively show the level of detail sufficient for a medical image.7

There are several important collections of dermatological photographs from that era. Alexander John Balmanno Squire’s Atlas of the Diseases of the Skin from 1865 and Howard Franklin Damon’s Photographs of the Diseases of the Skin from 1867 are important examples of texts published using some of the first medical photographs.8 These, along with William Herbert Brown’s collection of dermatological photos from the early twentieth century, give us important insight into clinical dermatology before the discovery of antibiotics, corticosteroids, and other modern drugs.11 Images have become an essential part of clinical dermatology of the twenty-first century.20 This paper aims to discuss the many uses of medical photography, its pitfalls and ethical implications, and the future of medical photography in dermatology.

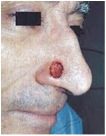

Photo from collection of William Herbert Brown11

Squire’s Atlas of the Diseases of the Skin1

Black and white photo that has been hand colored to show detail

Medical images offer as much to patients as they do to physicians and researchers. They enhance the doctor’s ability to communicate with their peers, their patients, and the public,8 and they add to research being carried out in the field of dermatology.1,5 They act as objective documentation of a patient’s condition, and the information contained within these images is often sufficient to make a diagnosis.1 Photographs help doctors maintain accurate records of their patients’ conditions10,20 and monitor the effectiveness of a specific treatment.2,19 This way, dermatologists no longer need to rely on their subjective, written descriptions and inconsistent memories of past appointments. Medical photographs are often used to educate patients on their skin conditions3,7 as well as to create images for dermatologic publications or presentations.14 They are also commonly used to teach dermatology to medical students and training doctors.3-5 Physicians may keep these photographs as documentation for insurance companies, or for use in the case of medico-legal action brought against them.19,20 They may also keep them as a personal record of the conditions they have encountered and treated.14

The advent of digital photography has offered considerable benefits to dermatologists using photography in their practice. Firstly, the overall cost of digital photography is much lower than that of conventional film photography.8 Furthermore, a digital photograph can be immediately assessed for quality, and erased and retaken if necessary.7,12 In addition, digital photos require very little storage space and allow quick and easy retrieval whenever necessary.2,14 Editing of a digital image allows dermatologists to add text to photos, such as a patient’s name or ID number, thus allowing them to set up an image based medical record system.5 In addition, lesions in a photo can be measured or enlarged, and photos can easily be copied or printed as necessary.5 Dermatologists can digitally modify photographs to demonstrate to patients how their skin may look once it has healed, or after a surgical procedure or reconstruction.14 Physicians can use a split screen view on their computer to view old and new images side by side for comparison and to show patients how their condition has changed.5,12 Digital photos will never fade, grow mold, get scratched or degrade in any way if stored digitally.5,14

Digital photography in dermatology forms the basis of Teledermatology, which is the practice of offering medical care based upon a diagnosis made from electronically transmitted information, such as a digital photograph.1,8 Many studies in the area of teledermatology have shown that in 59-93% of cases, a referral and history from a GP sent together with a photograph to a dermatologist may in fact be enough for the dermatologist to make an accurate diagnosis and recommend treatment without actually seeing or physically examining the patient.16 In addition, teledermatology may reduce the number of patients requiring an outpatient appointment with a dermatologist by 25%,19 thus shortening waiting lists and overall wait times. While there are some limitations to this practice, it may prove very useful for people living in distant rural and underserved communities with no access to dermatological specialists.8 Since diagnosis by photograph is not 100% accurate, even by the most experienced of dermatologists, further problems may arise if an inaccurate diagnosis is made and the incorrect treatment is given to the patient. In such a case, treatment time may actually be increased if the patient then has to wait for an appointment to see the dermatologist and get the correct treatment for their condition.16

There are some pitfalls in medical photography that must be addressed when a physician decides to use photography in their practice. Clinical photos can be very useful, but only when the photo accurately portrays what is seen in reality. For example, when using a ring flash on a camera, the image produced is often not the same as is seen with the naked eye.13 While the impulse of light is important for reducing blurring of the image and producing clear, colour balanced photos, being too close to the patient may give the skin a smoother look than in reality, and may produce a different shading pattern on their skin.13 These qualities are important for analyzing the three dimensional surface structure of the skin, and therefore when these are affected, analysis of the skin is affected as well.13

There are also many ethical considerations that need to be taken into account when using photography in the dermatological setting. There exists legislation that outlines the amount of time medical records must be kept before being destroyed.20 If medical photos of a patient are considered to be a part of their medical record, then should simply deleting a digital photograph due to poor quality be synonymous with destroying part of a patient’s medical records? Some American states argue that destruction of medical records is proof enough that a physician has committed malpractice, and can be used against them to establish liability in court.20 However, if images are taken for a purpose other than a patient’s care, such as for a clinical trial, or for a publication, it is unclear whether these photos would be considered a part of that patient’s medical record.20 Similarly, there is much debate regarding digital manipulation of a photo to enhance it for clinical interpretation. What extent of image adjustment is considered ethical, and how can this be monitored and regulated?8 For this reason, it is recommended that physicians save a copy of the original image as well as the manipulated copy to avoid dispute regarding how much an image has been changed.20 With the emergence of email and the Internet, digital images can easily be transmitted and copied, which could pose a threat to patient confidentiality. Doctors must be extremely attentive to ensure that images remain confidential and in a fully regulated environment.9,20 A final issue in relation to medical photography is patient consent. In a questionnaire sent to physicians around the UK in 2001, only 64% of hospital consultants and 40% of dermatologists obtained written consent to photograph their patients.7 Photographing patients without informed consent is considered unethical, and therefore consent should always be obtained, just as for any other medical procedure.7,9

With technology changing almost everyday, the boundaries of medical photography seem almost endless. A digital imaging system is currently in development to assist in diagnosing malignant melanoma in patients by scanning and evaluating the characteristics of a suspected lesion.8 Similarly, as software continues to improve, it seems that in the near future doctors will be able to analyze skin lesions three dimensionally and track them over time.5,8 Teledermatology will continue to improve as digital cameras improve, which will hopefully have a positive impact on patient outcomes and healthcare costs.8 As technology moves forward, it is important that dermatologists embrace the advances that will enhance the practice and education of dermatology.8

References

- Papier, A., Peres, MR., Bobrow, M., Bhatia, A. (2000). The Digital Imaging System and Dermatology. International Journal of Dermatology. 2000;39:561-575.

- Levy, JL., Trelles, MA., Levy, A., Besson, R. Photography in Dermatology: Comparison Between Slides and Digital Imaging. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2004;2:131-134.

- Shriner, DL., Wagner, RF. Photographic Utilization in Dermatology Clinics in the United States: A Survey of University-Based Dermatology Residency Programs. Journal of American Academic Dermatology. 1992;27:565-567.

- Mitchel, JC. The Teaching of Dermatology to Undergraduates at the University of British Columbia. III Role of Photography. Canad. M.A.J. 1961;84.

- Stone, JL., Peterson, RL., Wolf, Jr., JE. (1990). Digital Imaging Techniques in Dermatology. Journal of American Academic Dermatology. 1990;23:913-917.

- Dobson, R., (2004). Photo Diagnosis Can Cut Waiting Times for Dermatology. British Medical Journal. 2004; 328:367.

- Strauss, RM., Goodfield, MJD. Digital Imaging in Clinical Dermatology Across the UK in the Year 2001. Journal of European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2003;17:285-287.

- Ratner, D., Thomas, CO., Bickers, D. The Uses of Digital Photography in Dermatology. Journal of American Academy of Dermatology. 1999;41:5:1, 749-756.

- Creighton, S., Alderson, J., Brown, S., Minto, CL. Medical Photography: Ethics, Consent and the Intersex Patient. British Journal of Urology International. 2002;89:67-72.

- Thomson, S. Section of Dermatology- Discussion on Photography in Relation to Dermatology. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1946;39:475-479.

- Jury, CS., Lucke, TW., Munro, CS. The Clinical Photography of Herbert Brown: A Perspective on Early 20th Century Dermatology. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2001;26:449-454.

- Kaliyadan, F. Digital Photography for Patient Counseling in Dermatology – a Study. Journal of European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2008;22:1356-1358.

- Ikeda, I., Urushihara, K., Ono, T. A Pitfall in Clinical Photography: The Appearance of Skin Lesions Depends upon the Illumination Device. Archives of Dermatological Research. 2003;294:438-443.

- Chilkuri, S., Bhatia, A. Practical Digital Photography in the Dermatology Office. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2008;83-85.

- Tucker, WFG., Lewis, FM. Digital Imaging: A Diagnostic Screening Tool? International Journal of Dermatology. 2005;44:479-481.

- Goodwin, DP., Policano, T., McMeekin, TO. Practical Clinical Dermatology: Photography with Professional Results. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1997;989-990.

- Scheinfeld, N. Photographic Images, Digital Imaging, Dermatology, and the Law. Archives of Dermatology. 2004;140:473-476.

- Kaliyada, F., Manoj, J., Venkitakrishnan, S., Dharmaratnam, AD. Basic Digital Photography in Dermatology. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology. 2008;74:532-536.

- Leggett, P., Gilliland, AEW., Cupples, ME., McGlade, K., Corbett, R., Stevenson, M., O’Reilly, D., Steele, K. A Randomized Controlled Trial Using Instant Photography to Diagnose and Manage Dermatology Referrals. Family Practice. 2004;21:54-56.

- Scheinfeld, N. Photographic Images, Digital Imaging, Dermatology, and the Law. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:473-476.

ANDREA MARKS completed her first undergraduate degree in honors kinesiology at McMaster University in Canada. She is currently studying towards a second degree in medicine and surgery (MbChB) at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. Andrea has always had a very keen interest in science and the workings of the human body as well as a love for photography. She therefore really enjoyed exploring how the art of photography can be used to enhance the field of Medicine, as we know it today.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2013 – Volume 5, Issue 4

Leave a Reply