Khwanchai Phusrisom

Stephen Martin

Mahasarakham, Thailand

The Siamese military presence

In July 1918, 1284 Siamese volunteers arrived in Marseilles by ship1. Their air force personnel did not see action because their training had not been completed before the end of the war. The ground troops (Fig 1) had been trained, but being too few to form an independent infantry unit were assigned to transport or munitions duties for the nearly 500,000-strong US Army assault on the Maas-Argonne from September 1918 until the armistice. Siamese medical orderlies also helped staff the Maas-Argonne and Champagne field hospitals. (Fig 2)

King Vajiravudh of Siam had studied at Oxford, and had accompanied his father to visit Lord Armstrong, the Newcastle gun manufacturer. In 1899 the King took part in military exercises as an officer in the Durham Light Infantry. A strong Anglophile he supported the allies, published on German war crimes, translated Shakespeare into Thai, and started the Thai Scouts. He was succeeded by his younger brother, who also went to Eton and studied artillery at Woolwich. This was just as well, because in 1893 a French warship threatened to destroy the royal palace if the French were not allowed to occupy a Mekong River buffer zone south of their colony of Laos. But guns from Armstrong’s factory had been installed to try to prevent such empire-building and can still be seen at the river’s mouth in Bangkok.

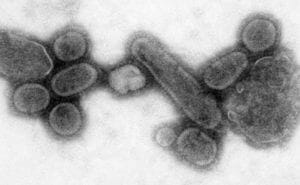

No Siamese soldier was killed in action during the war but seventeen died in France and Germany after the armistice2, mostly from the Spanish Flu (Fig 3). Gaysorn, a Siamese Expeditionary Force veteran, described in his report very ill flu cases, unconscious, having rigours, crying for home and for their parents. 3

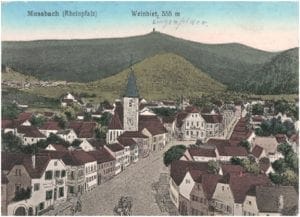

Most of the Siamese deaths occurred in the strategically important German Rhineland Palatinate (Pfalz) town of Neustadt an der Haardt and its surrounding villages, which the Siamese occupied peacefully along with French soldiers after the armistice. Later Nazi propaganda changed the name to Neustadt an der Weinstrasse. For five years after 1945 it used the original name, then reverted to Weinstrasse.

German newspaper reports

In the Neustadt Town archive we reviewed local newspaper reports on the flu (die Grippe) and the allied occupation before and after the armistice. There were no news other than the French occupying the Rhineland and no mention of non-French allies being present.

We read original German gothic script copies of three daily newspapers from September 1, 1918, to March 31, 1919; the ‘Pfälzischer Burger Zeitung’ (PBZ, Palatine Peoples’ Paper) and the ‘General Anzeiger’ (GA, General Gazette) covering several towns west of the Rhine from Frankenthal to Landau with Neustadt in between. We also reviewed the local paper for Neustadt and surrounding villages, the ‘Stadt und Dorf Anzeiger’ (SDA, Town and Village Gazette). These papers were all four-to eight side broadsheets, comprising all possible local dailies.

Reports of the flu were limited to October 12 to 30, 1918, following which there was mainly coverage of the armistice negotiations. After November 11 news of the threat of the Communist insurgency in Berlin took over, and there was no more news about the flu for the next twenty weeks.

The first mention was in GA, describing a rapid spread of the flu in rural and urban areas, and over 1000 cases in Milan. No specific local information was given. Six days later local school closures are reported without detail and on October 21 the paper warned of the need for hospitalizing and investigating patients with high fever. Aerial transmission risk was highlighted and two local deaths children under nineteen months of were mentioned.

On October 16 the SDA described local flu totalling 2000-3000 cases. The PBZ on October 19 had an article under the inside page headline ‘Die Grippe in Neustadt,’ saying that in the previous eight days 248 cases of flu had been registered at the hospital at the rate of 22-46 patients per day. On October 22 daily flu deaths in Landau with angina and pneumonia were recorded. The next day in Hassloch, just east of Neustadt, the schools were closed. On October 24 flu prevention measures were listed thus:

- The flu is ordinarily transmitted by coughing and sneezing

- Every case of flu should stay in bed. One in seven cases need to be hospitalised

- Avoid getting together with people in closed rooms

- Do not cough or sneeze at people, cover with your hand and turn your head away

On October 29 ‘many deaths’ from flu were reported in Neustadt, the common cause being pneumonia. In Deidesheim, a little north of Neustadt, children and middle-aged people (notably, not babies or the elderly) were described as particularly vulnerable to the flu. The final flu item was on October 30 with the report of the flu death in Frankenthal of a sixty-five year old headmaster and composer, Herr Julius Schmitt.

The papers covered the detail of the war in a far more factual manner than the later gross distortions and minimisation of the Nazi newspapers (Fig 2). ‘Trench action in Champagne’ was reported in PBZ on April 10, 1918, and ‘new heavy fighting in the West’ on November1. Only six days later the German delegation set off to Paris to sign the armistice.

PBZ reported that half of the Pfalz had been occupied by French troops by June 12, 1918, and that several new groups had arrived that day. On December 7 the evening SDA reported that ‘around 300-strong colonial troops’ with several officers got off the 1.45 pm train from Kaiserslautern and marched up Friedrichstrasse towards Mussbach village in helmets, with rifles and sidearms. They were ‘Frenchmen and Moroccans…, … brown and black….’. A further ‘500 colonial troops’ were expected to come that afternoon and were to be billeted in the school. No Siamese soldiers were mentioned specifically but they were probably present as the report fits Gaysorn’s description of the arrival, numbers, Mussbach destination, and timing. (Fig 4) As Siam had never been colonised, the reference to colonial troops was clearly erroneous.

On Christmas Eve the SDA described French uniform ranks. There were several advertisements for French language courses and several columns warning the public to protect against ‘sexual disease’, but not saying how. There was one advertisement for ‘treating women’s problems,’ but not saying what or by whom. German civilians likewise received only scant advice 4. As the flu was only identified as viral in 1933, there were initial rumours among the Siamese that the flu was due to German poison. These rumours ceased once the German villagers gave them soap and chocolate; and some Fräuleins followed the Siamese by civilian train to their final placement in Hochspeyer. On finally leaving Neustadt, the Siamese were waved off by a seething crowd in tears, including people from Neustadt as well as Mussbach and Hochspeyer villagers with flowers and presents.

Differential Siamese–US flu death rates

In the war more US troops died of the flu than in combat. 5 Of 150,000 in US training camps, some 30,000 or 20% died of the flu. The Thai flu mortality rate was much lower, possibly because the Thai group was more protected by being more isolated, but also perhaps because of different viral response genes in certain groups, such as black Africans6 and Chinese7 producing more flu-response cytokines8 and developing more fatal pneumonitis,9 in contrast perhaps to reduced cytokine response in ethnic Indochinese Thai people.

Aftermath

Siamese medical orderlies went through gruelling field hospital work yet went relatively-unsung. The Siamese soldiers participated in the Paris Victory Parade under the Arc de Triomphe, but the orderlies did not parade as they were largely still on duty3 and sadly were not accommodated.

Siamese troops played a small but effective role in pressuring Germany into signing the armistice. Some Siamese did sacrifice their lives but not in a way they might have predicted. The solders were cremated in France and Germany, their ashes taken back to Thailand and ceremonially interred later in 1919, under the King’s supervision2, in a handsome white chedi or stupa, a Buddhist monument that still stands in a corner of the Sanam Luang – the Royal Field – in Bangkok. All nineteen victims were awarded the Order of Rama, with a purple ribbon like the Victoria Cross and the Hindu deity who remains the hero in the Ramakien, the Thai version of the Ramayana.

References

- The Great War 100 years on, never to be forgotten. Lakmeuang Journal, Thai ministry of defence. 2014; vol 284: 12-15. In Thai.

- Whyte B, Whyte S. The inscriptions on the first world war volunteers memorial, Bangkok. Journal of the Siam Society. 2008; vol 96: 175-192.

- Gaysorn, Sgt Kleuap. The history of the Royal Transport Corps at war in Europe. Rung Reuang Tam Publishing, Bangkok, 1958. In Thai.

- Appler, A C. Put a helmet on your privates because they’re going to see some action: the history of condoms in the military. Hektoen International, Spring 2016.

- Byerly, C R. The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919. Public Health Rep. 2010; 125(Suppl 3): 82–91.

- Quinn S C, Kumar S, Freimuth V S, Musa D, et al. Racial Disparities in Exposure, Susceptibility, and Access to Health Care in the US H1N1 Influenza Pandemic. American Journal of Public Health: February 2011; Vol. 101, No. 2, pp. 285-293.

- Zhang Y, Makvandi-Nejad S,Qin L, Zhao Y, et al. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein-3 rs12252-C is associated with rapid progression of acute HIV-1 infection in Chinese MSM cohort. 2015 May 15; 29(8): 889–894.

- de Jong MD,Simmons CP, Thanh TT, Hien VM, et al. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat Med. 2006 Oct; 12(10):1203-7. Epub 2006 Sep 10.

- Kash J C, Tumpey T M, Proll S C, Carter V, et al. Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. 2006 Oct 5; 443(7111): 578–581. Published online 2006 Sep 27.

Further reading

Phusrisom K. Soldiers of Siam. A First World War Chronicle. Lemongrass Books, Durham, UK, 2020.

Acknowledgements

We thank the kind staff of the Stadtarchiv in Neustadt an der Weinstrasse for their comments, for lifting out many large folios, and for allowing photography without hesitation.

KHWANCHAI PHUSRISOM holds Thai degrees in Computing and Accountancy. A member of the British Society for Eighteenth Century Studies, she has researched for English Heritage and the National Trust, of both of which she is a life member. She has directed Heritage Open Days with European Union support in Britain and Germany.

STEPHEN MARTIN is a retired UK Professor of Neuropsychiatry, currently Visiting Professor, Faculty of Arts, University of Mahasarakham, Honorary Professor of Psychiatry, University of Chiang Mai, and a member of the Siam Society. He holds the German language exam for medical practice in the Rhineland.