Anne Jacobson

Oak Park, Illinois, United States

Image by Anne Jacobson

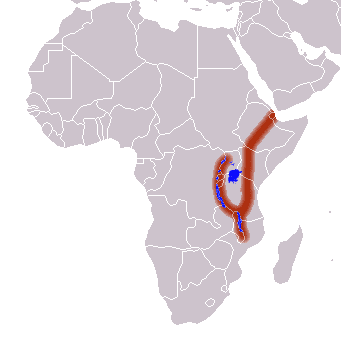

In the vast, parched desert of Africa’s Great Rift Valley, night fell like an ocean wave, predictable yet unexpected, with weight and substance and astonishing force. The darkness filled our eyes and expanded our lungs, enveloped our salty skin. Each evening the last rays of equatorial sun bathed our bodies as we washed on the shores of Lake Turkana, the village children splashing with us in the murky water, our playmates and protectors. They squealed and giggled and repeated our words, scattered the flocks of startled flamingos, and scanned the surface for the bulbous eyes of Nile crocodiles and hippos. In these moments before nightfall, gathered at the ancient, salty lake, our dusty skin was transformed to glistening amber and onyx. When darkness came, we parted ways: the children back to the vigilant protection of the tribe, and we to the solitary house and clinic on the outskirts of the village. Rhythmic heartbeat drums emerged from the center of the palm-thatched dwellings, floated into the velvet night, rippled the surface of the briny lake, drifted over motionless acacia trees, and disappeared into mountain shadows. I longed to sit in the circle of fire and dancing, to witness the community rising from the burnt offering of the blistering day. There would be no invitation to that circle of light, for reasons as layered and true as the ancient sediment beneath my feet, the cracked clay where our hominid ancestors first walked upright, and which now yielded precious clues to our shared and complicated human history. I sat instead outside of the circle, but under the same great dome of innumerable stars and streaking meteors. I tried to learn to see in the dark.

Darkness in this remote desert valley was complete, a welcome respite from the parching heat. Night provided relief from the physical intensity of equatorial sun, but my eyes and mind also needed the inky darkness to process the realities witnessed in the light of day. I was a fourth year medical student: wise enough to know that my main role in this outpost clinic was simply to observe and to learn; wide-eyed and adventurous enough to embrace a two-month journey that was wild and a little dangerous; and naive enough to believe that my Western medical education would bear more than a marginal usefulness. The lessons I would carry out of the desert bore little resemblance to a medical textbook, but would forever change the way I saw myself and the world of medicine in which I was becoming initiated and immersed.

My supervisor was a young Spanish physician with a medical degree but no residency training. I followed two kind but weary nurses, both serving out government obligations from other parts of Kenya and regarded as foreigners by the wary Turkana people. They treated the common conditions at the clinic with a calm and detached efficiency: fungal infections, vitamin deficiencies, parasites, malnutrition, malaria. Twice a month we loaded the Land Cruisers to set up a mobile clinic in even more remote settlements, providing vaccinations, prenatal care, and basic medications under the shade of an acacia tree. The doctor and I staffed more complicated cases as requested by the frontline nurses: the elderly man with a deep thigh wound that had been draining for months; the teenage boy with advanced exophthalmos from untreated hyperthyroidism; the smiling young girl with a heaving heart and a thrill that vibrated the tribal beads adorning her chest. These patients could sometimes be treated at the district hospital, which involved a grueling four-hour trip over rutted roads that transformed into rushing rivers in a seasonal downpour. More advanced treatment could only be provided in Nairobi, a two-day trip and a lifetime away. Hospitals did not accept Turkana currency — camels, goats, beads — if there was any currency to be spared during these long years of drought. Multiple levels of negotiation were required for the treatment of one patient: with doctors and hospitals, parents and spouses, village headmen and chiefs. These negotiations were even more complicated if the patient was a woman, especially if there were no other wives in the household to cook the food, gather the water, repair the house, and care for the children.

Survival in the desert is a full-time job, and the proud Turkana women were experts in their field. Rising before the sun, they carried water on their heads and children on their backs, their graceful necks invisible under tiers of colorful beads and skin caked with protective layers of red clay. Twenty years of drought had made their nomadic lives even more difficult, as their children suffered with malnutrition and neighboring tribes raided their villages. A woman who was young and healthy would bring a dowry of many camels and goats, central as she was to the survival of the family unit. But a woman who was weakened by illness, or had otherwise been excluded from the community, often found herself vulnerable and alone.

We encountered one such woman on a visit to a small subdistrict hospital, an open-air, cement structure lined with metal cots and thin, sagging mattresses. A withered and skeletal figure was curled on a cot in the corner, her unblinking eyes and cracked lips covered in flies. She appeared to be an old woman, perhaps dying of tuberculosis or an undiagnosed cancer. My gut clenched in disbelief when the attendant informed us that she had given birth some days before. The infant had died, and she herself was now was dying from infection, despite the bag of penicillin attached to an ancient IV pole. The attendant gave her some sips of water, which she promptly vomited. He gently cleaned the vomit from her naked chest. Weakened by malnutrition, her body would succumb to this infection. She would not survive a trip to the larger hospital. Patients that were able to make it to the district hospital, where a life-threatening condition could be more adequately treated, would often sleep head-to-toe, two patients to a cot without bedding, in long, concrete wards. A family member was required to bring food for the patient, as it was not provided by the hospital. Chickens wandered between the cots, and flies buzzed around unemptied bedpans. The hospital staff was efficient, stoic, and stretched so thin as to be nearly invisible among the fetid sea of bodies.

The health needs of the population were simple, and remarkably complex. To deliver health care, which often meant the provisions of basics such as food and water more than any medication or procedure, was to tread in an intricate web of tradition, education, history, belief, environment, infrastructure, and government. My medical training to that point had been a fairly straight highway: pick the correct medication to treat the condition, the right procedure to correct the anomaly. In Kenya that highway might initially appear straight, but on approach one often found that the road had been washed away in the latest storm, and a longer, more circuitous approach would be required. I would learn later on, as a primary care physician in America’s inner cities, that the road to deliver health care is rarely straight or in good repair, even in a place as wealthy and developed as our own country. I would find similarities in the intricacy of the forces of will and belief, of politics and poverty. In Kenya, the difference was immediate and stark—between what was and what could be, between simple cause and devastating effect, between the blinding illumination of day and the quiet contemplation of night. In the United States, poverty and prejudice create barriers and conditions that may be as harsh as the Kenyan desert, with effects that are sometimes just as stark and immediate. At other times the consequences are slow and insidious, but equally devastating.

I’m not sure that I ever really learned to see in the dark. The young woman that went to Africa perhaps expected lessons that could be packaged as neatly as a medical school lecture, regurgitated like a differential diagnosis, or chosen from a lineup in a multiple choice exam. The woman that continues to ponder that experience twenty years later knows that lessons learned in the dark reveal themselves slowly, unexpectedly—crashing with the ocean wave force of night in the desert, or appearing in fleeting moments like a mirage on a desert highway.

The Great Rift Valley is a land of evidence, both ancient and new, of the contrasts and divisions between us, and of the ways we are family at our deepest core. The land itself bears the bones and fossil footprints of our human ancestors—who adapted and walked upright, who learned to survive by forming communities, who began an epic human journey. Humanity is still learning, adapting, struggling, resilient. We furiously attempt to build the highways of destiny by day, and forget the ways in which our lives are woven together like webs spun in the dark. We are still participants—and companions—on an epic human journey.

ANNE JACOBSON has worked as a family physician and health care administrator for the Ambulatory and Community Health Network of Cook County in Chicago, IL, and PCC Community Wellness in Oak Park, IL. She has worked internationally in Kenya, Thailand, and Mexico. Her writing has appeared in JAMA: A Piece of My Mind, and in the anthology At the End of Life: True Stories About How We Die (In Fact Books, 2012). She lives in Oak Park, IL.