Michael Meguid

Marco Island, Florida, United States

In fragmented pieces, revealed casually and interspersed with daily political news, Zan gradually painted his life as a gentleman farmer in Orange County. In a moment of bravado he said, “I’ve had it for so many years and it hasn’t bothered me, it’ll probably be all right, Doc.” After a swig of his beer, he added, “If you’re willing to fix it I’ll let you do it someday. I don’t trust doctors, but you’re different.” In August 1978 we moved to Los Angeles. The van had barely left when Zan padded across our cul-de-sac, shirtless in knee-length shorts, concealing a bulging large mass he called “my benign sliding inguinal hernia.” At sixty-five, he was a tall, stocky man with a crop of wavy white hair.

Eventually Zan made an appointment. His hernia reached his left knee. Elsa, my resident, had not seen anything like it—I had, in India. He lay back. I successfully reduced it.

“An operation will fix your problem.”

“It doesn’t show,” he argued. “Why fix it?”

“If you aren’t willing to fix it under controlled conditions, will you be willing when it’s strangulated and a life-threatening emergency?”

His operation was my first of the day. Backing my car out of our driveway, I failed to note signs of inactivity across the street, riveted by news that Iranian Revolutionary Guards had stormed our embassy and taken fifty-two hostages.

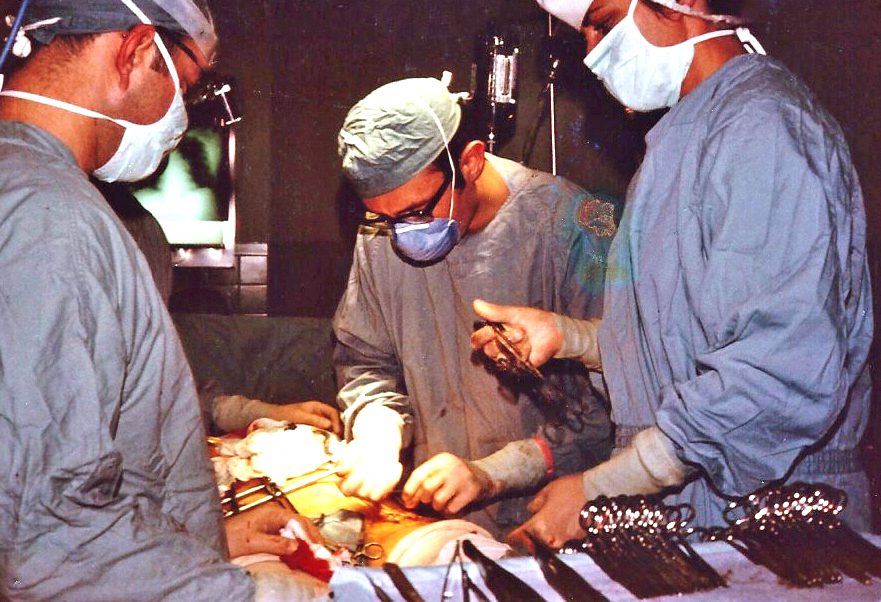

My usual surgical team, including my scrub nurse, and the operating room (OR) were ready. We hung around in our blues, expecting Zan at any moment. We continued to wait. I grew frustrated, believing Zan would turn up, then incensed at being let down.Still smarting, by 9:30 I called for my next case. My team disbanded and a different nursing team turned over the OR while Mr. Nazari was wheeled in. A new scrub technician who was unknown to me at the time kept irritating me by asking numerous questions about what instruments and sutures I was going to use. It was more efficient and safer to work with my familiar team.

Mr. Nazari was a frail seventy-three year old Iranian who spoke no English. I no Farsi. In my office, his son-in-law had translated our exchange. He had a small cancerous ulcer on his tongue confirmed by biopsy. I recommended its excision. His chest x-ray showed smokers lungs, and his electrocardiogram indicated cardiac enlargement. Unlike Zan’s operation, for which I had allowed three hours, Mr. Nazari’s was a straightforward one-hour case.

On the operating table, monitors were attached. Pre-occupied with Zan’s no-show, Elsa and I scrubbed, gowned, and gloved silently. Mark anesthetized Mr. Nazari and inserted a nasotracheal tube. His face was painted with antiseptic solution, draped, leaving only his mouth exposed. I packed a gauze ribbon at the back of the throat to prevent blood trickling into his lungs. I had ordered my usual local anesthetic, 0.5% Lidocaine with Epinephrine, to inject around the ulcer to minimize bleeding.

I broke the silence. “Stitch.”

“Which one?”

Surprised, I said, “The zero Proline on a three-quarter round needle.”

The new scrub hesitated, uncertain, then loaded it on a needle holder, and passed it to Elsa, who stuck it through the tongue’s non-vascular mid-line raphé. The ends were clamped together to facilitate moving Mr. Nazari’s tongue.

Concentrating on the operative field, I held out my hand expecting the local. My hand remained empty. I looked up, losing focus. The scrub stood, waiting, having never assisted on a similar case. The tension in the room rose like thickening fog. My mood further darkened. Elsa and Mark exchanged glances.

“Local.”

“Which?”

The scrub nurse repeated the question, a tone of frustration creeping into her voice.

“Local anesthetic: the Lido with Epi.”

“Epinephrine?”

“Yes.”

A flutter of activity followed. The circulating nurse opened a vial; the scrub drew up the solution. Mark had his back to the scrub table. Elsa busied herself, using the sucker to clear out the saliva from Mr. Nazari’s mouth. I felt horrible, mired in a foul mood.

We waited.

The scrub handed me the syringe. I took it, fleetingly noting no label. Elsa tugged on the tongue-suture, exposing the ulcer.

“Injecting!”

Mark noted my action on the anesthesia record and glanced between the cardiac monitor and me, asking,“How much?”

“Five milliliters,” I replied.

Quivering, he shouted. “Hold it! He’s going into V-tach.”

We froze. Mr. Nazari’s heart had gone into ventricular tachycardia, a potential harbinger of worse to come. Beads of sweat collected under my mask. Mark’s monitor showed cardiac contractions of 100 beats per minute, which changed to erratic squiggles. I lowered the head of the table to get more blood to Mr. Nazari’s brain. Mark injected antidotes, shouting,“Cardiac arrest!”We had four minutes to restart the beating of Mr. Nazari’s heart.

“Code blue. OR three,” blasted over the loudspeaker system.

“What the hell did you give me?”

“Epinephrine, like you said.”

“Neat epinephrine?”

“Yes.”

“Are you fucking crazy? The premix local!”

“You said epinephrine,” she repeated, distraught.

I whipped off the drapes. Elsa started cardiac massage. The resuscitation team entered. One of them relieved Elsa in cardiac compression. There were no spontaneous heartbeats.

Two minutes elapsed. “Stop pumping,” Mark declared. Mr. Nazari’s EKG showed too few spontaneous heartbeats to sustain him. Taking over, I forcefully compressed his chest, determined that he would live. Suddenly I felt cracking under my hands as his frail ribs fractured.

“Chest x-ray. Stat.”

The machine with its technician appeared; an x-ray plate was placed behind Mr. Nazari’s chest and with a cry of “x-ray!” the OR cleared of women. The men scurried behind a lead shield.

How long to continue was my call. Mr. Nazari had entrusted me with his life. His cardiac arrest was avoidable. I was indifferent to the murmurs that he was old and had cancer as I continued. By fifteen minutes,the code members quietly drifted out, suspecting they were dealing with an increasingly lost cause, thinking I was in denial.

Mark, Elsa, and the nurses remained, together with Mr. Nazari and his cancer. By the sixteenth minute, the epinephrine was wearing off. The natural“beep-beep” of his cardiac monitor was audible; he had a pulse. He lay on the OR table receiving oxygen, eyes closed, and alive. His pupils responded to light. We took a collective deep breath.

I was determined to excise the ulcer. Mark agreed. The patient was as stable as he’d ever be. While the room was refreshed, I went and saw his family telling them of the events. I maintained my professional external demeanor. Inside I was profoundly sorry and ashamed.

“Thank Allah he is alive,” said his daughter in a distinct Iranian-English accent. Her husband thanked me repeatedly. In my state of profound remorse, their gratitude was unwelcome.

Back in the OR, Elsa placed bilateral chest tubes and a Foley catheter, and I excised the ulcer. The mood was solemn.By 3:30pm Mr. Nazari entered the intensive care unit.

Cars whizzed by me as I drove home on the freeway at a crawling speed, feeling utterly dejected. How could I have created such a disaster merely because Zan’s no show wounded my pride? I had not made my request for local sufficiently clear to the new technician. I had blindly trusted someone I had never worked with before. I had accepted an unlabeled syringe full of an unknown solution. I never apologized to her, Mark or Elsa. It was easier to apologize to Mr. Nazari’s family than to my colleagues. How could I face my wife and children?

Arriving home, Zan moseyed over. “Doc, they invaded our embassy in Tehran,” he stated. Seeing my face, he tried to disarm me. “You’re not mad that I didn’t come, are you? How could I when our boys were captives? They needed my support. Look…” A huge 5’ x 8’ flag hung on the façade of his house.

“That flag flew over the Capitol in 1948. President Truman gave it to my Poppa. I’m going to fly it until our boys come home.” Sensing my dark mood, he ambled back. Despite Zan’s explanation, I was angry with myself for making a near fatal mistake. In my heart, I knew he did not do anything maliciously. Our shared pride for this country made me empathetic. He flew “Old Glory” continuously as the hostage crisis paralyzed Carter’s presidency.

I visited Mr. Nazari daily. In January, 1980, he was moved out of the ICU. Seeing Zan’s flag each morning and evening gave me great satisfaction. I admired his resolve.

In the fall of the same year, Zan appeared in the pre-op holding unit. I was waiting for him—twelve months after his first appointment. Since then Mr. Nazari had survived to go home, and I had grown wiser.

In the OR, the anesthetist started to place a mask on Zan’s face. He pushed it aside and asked, “Doc. When can my wife have sex?”

“Anytime, but you’ll have to wait six months,” I joked. I felt a sense of closure as I operated on his massive hernia containing the sigmoid colon.On the fourth post-operative day, Zan went home. On parting he asked, “Doc, what happened to my nuts?”

“Your crown jewels are still there.”

He looked down, “But they used to nearly reach my knees.”

Later that month, after 444 days in captivity, the hostages were released. Zan moseyed over, beer in one hand, the triangularly folded flag in the other. It has decorated my wall ever since.

MICHAEL MARWAN MEGUID, was Born in Egypt, spent his childhood in Germany and England, where he attended University College Hospital Medical School, London, followed by surgical residency at Harvard Medical School. As a surgeon/scientist in oncology and clinical nutrition, he earned a PhD in nutrition at MIT. While operating and researching at Upstate Medical University, Syracuse he authored over 400 scientific papers and founded the International Journal, Nutrition, of which he serves as Editor Emeritus. On retiring, he earned an MFA from Bennington Writers Seminars, VT. He lives and writes on Marco Island, Florida

Leave a Reply