Lawrence Zeidman

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Introduction

|

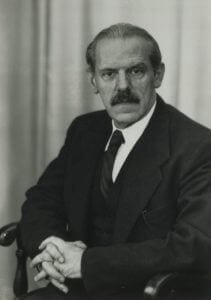

| Walter Rudolph Kirshbaum Reprinted with permission from the Center for the History of Neurosciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Neurology and Rehabilitation |

The purge of thousands of “non-Aryan” physicians, including many neuroscientists, began within the first few months of the Nazi takeover of Germany in January 1933. At that time, roughly 9,000 “non- Aryan” (full Jews, baptized Jews, part-Jews, and other minorities), and politically dissident doctors lived in Germany,1 comprising 15-17% of all German physicians.1,2 Roughly 6,000 of these physicians emigrated, and the remainder committed suicide or were murdered in the Holocaust.1 Over 150 emigrants were neuroscientists,3-6 and the US was their most common destination.1 Some neuroscientists immigrated to Chicago permanently, where they found a haven from persecution and oppression.

The neuroscientists

Hermann Josephy (1887-1960), trained in Rostock,3 was a World War One veteran,9 and became “extraordinary” professor and chief of neuropathology at the University of Hamburg.3 His teaching license was revoked in September 1933, but he continued private practice and hospital work (without reimbursement) until his medical license was withdrawn in 1938 and his post taken by an “Aryan” Nazi neuropathologist. He sent his children abroad to England and Palestine in 1936; and in 1938, due to having very little income, he was forced to move and sublet his apartment. During Kristallnacht, he was one of 600 Hamburg Jews deported to concentration camps throughout Germany, spending over a month at Sachsenhausen (near Berlin) under brutal conditions. He was released when his wife produced documents proving their intended emigration. After being forced to liquidate most of their assets to pay Nazi flight taxes, they immigrated in April 1939 to the UK. There he worked briefly in an unpaid research position but in 1940, he was interned as an “enemy alien.”8

In October 1940 Josephy immigrated to Chicago9 and obtained an Illinois medical license in 1941.8 He worked and lived in central Illinois in a state mental institute for the “feebleminded,” He was not satisfied with the income and conditions and lack of opportunities to continue his research. In 1945 he became director of a laboratory at the 4500-bed Chicago State Hospital, finally again practicing as a neuropathologist.8 From 1949-1952 he was an associate professor at the Chicago Medical School.3,7

Walter Rudolf Kirschbaum (1894-1982) from Duisberg, Germany, was a lecturer in neuropsychiatry at the University of Hamburg from 1921-1934, but worked primarily as a neuropathologist.10-12 In March 1934 he lost his teaching license and in June 1934 was dismissed from the University,13 but continued private practice out of his apartment.9 Like Josephy, he was also imprisoned in Sachsenhausen from 1938-39 during Kristallnacht, but with the help of his Christian wife he was released, and the family immigrated to Chicago in 1939.9,11,12There Kirschbaum completed an internship at Michael Reese Hospital (MRH) and eventually became board certified in neurology and psychiatry in 1942. He worked at first in a mental hospital and a correctional facility,10 but he was unhappy with the lack of research.11,12 In 1948 he was invited to join the neurology department at Northwestern University as an unsalaried assistant professor, but also continued in private practice, and in 1952 was appointed chair of neurology at Cook County Hospital.10,12 Eventually he was awarded extraordinary professor emeritus by the University of Hamburg13 and promoted to associate professor (emeritus) at Northwestern in 1958.10,11 From after his immigration to the US he eventually had at least 53 articles and book chapters to his name.10 He also collected all the Jakob-Creutzfeldt Disease (CJD) cases he could find and wrote a book summarizing the first 150 cases.11,14

Ernst Haase (1894-1961) was born in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia).15 He served in WWI from 1914-1918, and obtained his medical degree from the University of Berlin in 1923. He worked over nine years in Medical Clinic IV of the Berlin University-affiliated Moabit Hospital,16 independently directing the neurological section from 1929-1930,17also directing the Welfare Clinic for Alcoholics and Drug Addicts,15-16 from which he was dismissed in 193317 and he went into private practice instead.15 In October 1938 Haase became a Krankenbehandler (Jewish “sick-treater”);17 however, he was able to leave for Britain,16 then came to Chicago in 1940.18 After an internship at Mount Sinai Hospital he became licensed in Illinois in 1941. He worked as an adjunct neuropsychiatrist, associate neurologist, and neuropsychiatric consultant at various hospitals, becoming clinical assistant professor at the Illinois Neuropsychiatric Institute in 1947.19

Discussion

The persecution experienced by these physicians was typical of the professional marginalization under the Nazi regime. Beside violence, propaganda, and harassment toward “non-Aryan” doctors throughout the 1930s,1,20 the Nazis passed roughly 250 laws stripping them of all professional rights in just eight years.20 All three neuroscientists were dismissed in 1933-34, unable to practice medicine, and by 1938, like all other Jewish doctors, became decertified. By early 1939, there were only 285 delicensed Jewish doctors in the entire German Reich, derogatorily called Krankenbehandlern, and they could only treat Jews.21 Haase became a Krankenbehandler prior to emigration. The coordinated Nazi pogroms in November 1938 (Kristallnacht, Night of Broken Glass) throughout Germany especially targeted Jewish doctors, the exclusive “prolongers” of Jewish life.1 It was very dangerous even for Krankenbehandlern to practice medicine at this time;1 they could experience violence, or be arrested and incarcerated in concentration camps. These hostages were generally released if they agreed to leave Germany and cede their property to “Aryans.”22 By 1938-39, the Nazis claimed up to 96% of Jewish assets prior to departure.1

Professional roadblocks for the neuroscientists were not over once they reached the US, but Illinois was a more liberal state for physician emigrants and also had a doctor shortage,23 especially for mental hospitals.18 Illinois was one of only 15 US states to relicense refugee doctors by 1940, and some hospitals such as MRH had special internship slots reserved for émigré doctors to meet the state requirement.24 But beside the psychological wounds to these neuroscientists, there was a definite loss in professional productivity. Their emigration was not merely a “brain drain” from Germany. For Josephy, Kirschbaum, and Haase there was an average 14.7 year gap between when they lost their respective position in Germany and regained a similar academic rank in Illinois. Kirschbaum and Haase had no publications between dismissal and establishing themselves in Chicago, and Josephy was unable to do any research for five years in Illinois. Germany’s loss was certainly Chicago’s gain, and Illinois welcomed these neuroscientists more than other states. But these neuroscientists lost many productive years due to Nazi persecution.

References

- Kater MH. The Persecution of Jewish Physicians. In: Doctors under Hitler. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 1989:177-221.

- Schmiedebach HP. Jüdische Ärzte in berlin. Wissenschaft und ärztliche Praxis im Spannungsfeld zwischen emanzipation und Antisemitismus (I. Teil). Berliner Ärtzeblatt 2002;116:14-18.

- Peiffer J. Die Vertreibung deutscher Neuropathologen 1933–1939. Nervenarzt 1998;69:99-109.

- Peiffer J. Hirnforschung in Deutschland 1849 bis 1974: Briefe zur Entwicklung von Psychiatrie und Neurowissenschaften sowie zum Einfluss des politischen Umfeldes auf Wissenschaftler. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag; 2004.

- Schwoch R, editor. Berliner jüdische Kassenärzte und ihr Schicksal im Nationalsozialismus: ein gedenkbuch. Berlin: Hentrich & Hentrich; 2009.

- Strauss HA, Buddensieg T, Düwell K, editors. Emigration: Deutsche Wissenschaftler nach 1933, entlassung und Vertreibung. Berlin: Technische Universität berlin; 1987.

- Archiv der Bibliothek für Universitätsgeschichte, Hamburg, Akte Hermann Josephy.

- Stellmann J-P. Leben und Arbeit des Neuropathologen Hermann Josephy (1887-1960): Sowie eine Einführung in die Geschichte der deutschen Neuropathologie (Medical Doctor Dissertation). Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf Institut für Geschichte und Ethik der Medizin, 2010.

- Von Villiez A. Mit aller Kraft verdrängt. Entrechtung und Verfolgung „nicht arischer“ Ärzte in Hamburg 1933 bis 1945. Dölling und Galitz Verlag München Hamburg 2009.

- Kirschbaum WR. Curriculum Vitae, March 12, 1958. Archives of the Chicago Neurological Society. Boshes Library of the Neurosciences. UIC Neuropsychiatric Institute, Chicago, IL USA.

- Boshes LD. In Memoriam: Dr. Walter R. Kirschbaum, 1894-1982. Archives of the Chicago Neurological Society. Boshes Library of the Neurosciences. UIC Neuropsychiatric Institute, Chicago, IL USA.

- Kirschbaum WR. Letter to Dr. Louis Boshes, June 12, 1970. Archives of the Chicago Neurological Society. Boshes Library of the Neurosciences. UIC Neuropsychiatric Institute, Chicago, IL USA.

- Archiv der Bibliothek für Universitätsgeschichte, Hamburg, Akte Walter Kirschbaum.

- Kirschbaum WR. Jakob-Creutzfeldt Disease. New York: American Elsevier Publishing Co; 1968.

- Anonymous. In Memoriam: Ernst Haase. Archives of the Chicago Neurological Society. Boshes Library of the Neurosciences. UIC Neuropsychiatric Institute, Chicago, IL USA.

- Curriculum Vitae and Affidavits, 1938, Walter and Li Friedländer for Ernst Haase and family. Box 3, Folder 78. Walter A. Friedländer Papers, M. E. Grenander Department of Special Collections & Archives, University Libraries, University at Albany, State University of New York.

- Baule C. Ernst Haase (1894-1961): Neurologe, Psychotherapeut, Sozialmediziner, Sein Leben und Werk. Dissertation, Medical Facutly of the Free University of Berlin, July 7, 1995.

- Box 3, Folder 79. Walter A. Friedländer Papers, M. E. Grenander Department of Special Collections & Archives, University Libraries, University at Albany, State University of New York.

- Anonymous. National Cyclopedia for American Biography entry for Ernst Haase. Box 3, Folder 81. Walter A. Friedländer Papers, M. E. Grenander Department of Special Collections & Archives, University Libraries, University at Albany, State University of New York.

- Proctor RN. Anti-Semitism in the German Medical Community. In: Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press; 1988. pp. 131-176.

- Efron JM. Before the storm. Jewish doctors in the Kaiserreich and the Weimar Republic. In: Medicine and the German Jews. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2001:234-264.

- United States Holocaust memorial museum. [United States Holocaust memorial museum, Kristallnacht page on the Internet]. Washington, DC: United States Holocaust memorial museum; c2012 [update 2012; cited 2012 may 2]. Available from: http://www.ushmm.org/museum/exhibit/online/kristallnacht/frame.htm.

- Edsall DL, Putnam TJ. The Émigré Physician in America, 1941: A Report of the National Committee for Resettlement of Foreign Physicians. JAMA 1941;117:1881-1888.

- Kohler ED. Relicensing Central European Refugee Physicians in the United States, 1933-1945. Simon Wiesenthal Center Museum of Tolerance Online Multimedia Learning Center. 1997; Annual 6: Chapter 1. Available from: [http://motlc.wiesenthal.com/site/pp.asp?c=gvKVLcMVIuG&b=395145]. Last accessed 8/29/13

LAWRENCE A. ZEIDMAN, MD is currently a practicing neurologist and assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine (UIC). He specializes in peripheral nervous disorders, and directs the EMG laboratory and the Clinical Neurophysiology Fellowship. He became interested in neuroscience and medicine under National Socialism in 2010, and has published or written nearly 15 articles on the topic, as well as teaching a class on the subject to UIC undergraduate honors students. He is also currently writing a book on the subject.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Summer 2014 – Volume 6, Issue 3

Summer 2014 | Sections | War & Veterans

Leave a Reply