Emmanuelle Godeau

Toulouse, France

In many medical schools, dissection of cadavers remains an essential component of the curriculum, even though surveys from the past 50 years have shown this is not the most efficient way of learning anatomy. Yet the persistence of dissections suggests a different role: a rite of passage and creating an esprit de corps for the profession. Our anthropological studies, in which one hundred medical students and doctors from France, Italy, Switzerland, and the United States were interviewed, support this thesis.1

An ambiguous necessity

When medical students anticipate their first dissection, they vacillate between anxiety, boasting, fear, and excitement.1 This echoes the ambivalent memories of older doctors, who often reminisced that “one can’t see anything.”2 Many students and experienced doctors have questioned the utility of dissections. A student from Italy remarked, “The general impression was that it was pointless.” An American pathologist said: “Much of the traditional anatomy curriculum is irrelevant to medical practice and might easily be eliminated.”3 Still, all doctors recall those sessions, and generally associate them so strongly with “tradition” and “custom,” that not following them would pose the risk of never becoming a doctor: “I wanted to see, because one has to go and see,” or as an American student said, “Everyone correlates being a doctor with the study of anatomy.”2

This necessity, vaguely felt by students and consistent with the claims of professors, leads us to interpret dissection exercises as the required setting of a specific experience, the place and time to acquire the knowledge that “builds the doctor.” Indeed, in the United States, anatomy professors insist that dissections are necessary for future doctors3 and specifically introduce them as ”rights of passage” 4,5 following recommendations derived from early teachings about anatomy in the fourteenth century,6 with the same paradoxes and contradictions.

Beyond this necessity, the importance placed on practical anatomy varies across countries. In Italy, dissections have become optional, and sometimes students just see a film. In Lund, Sweden, dissections have been replaced by work at a computer with software that creates three-dimensional views of the body, simulating dissections.4 In Hannover, Germany, students work by anatomical zones studied from clinical examination, radiology, pathology . . . to dissections. In the US, medical students historically have had to perform dissections in small groups in their first year, often for a full semester.7,8,9 Nowadays, time spent in dissections seems to be shortening and even approaching disappearance globally,4 but the best students are encouraged to dissect outside of the regular curriculum.10 In Toulouse, France, dissections are still compulsory, graded and assessed by oral exams. However, each student does not have to dissect, as was the case until the 1970s.

From corpse to “anatomy”

During their first dissections, students go through an ordeal, physical and mental, which is intrinsic to their apprenticeship. Now as in the Middle Ages, one has to learn to overcome the offense made to their senses.

The first offended sense is smell. In Oman, over 90% of students reported being upset by the smells.11 Sight is the second tortured sense, because of the color and global aspect of the corpses. Not many students will actually touch them, those who dare will insist: the corpses have nothing in common with human bodies.

The confrontation of corpses leads students to manipulate them in ways consistent with the technical requirements of dissections, but that also changes these worrying bodies into “anatomies,” emblematic of the knowledge to be learned in lab work. A new code of perception and this new setting5 help students to distance themselves from their emotions. Meanwhile, using un-academic methods, they begin to professionalize their perceptions and ways of dealing with nakedness and death, also essential in becoming a doctor.

To protect themselves from the musty or decomposing smell of the corpses, they use many methods: perfumed handkerchiefs, scarves, turtle necks pulled over the nose, or, in England, Vicks VapoRub®.2 These have often now replaced tobacco smoking as a means of masking offensive smells. Thus, clouds of smoke or perfume allowed the students to submit corpses to a gradual metamorphosis: their repulsive materiality is replaced by waxwork dummies like those found in anatomical museums, meeting an image suggested by an English student in the 1940s about the anatomy lab: “A vast and sinister green-house growing waxen bodies in rows.”12

A less common form of protection is fainting: “we were all obsessed by this idea: not to faint.” Sinclair, an American sociologist that studied medical apprenticeship in the late 80’s, notes that one of the first questions freshmen ask older medical students is, “Do people faint in the dissection room?”13 American students interviewed by Segal , an anthropologist that worked on medical students from the East coast in the 80’s, were more explicit: what they fear in fainting is that others might doubt their capacity to become doctors, showing how early the medical model is internalized.8 An interviewed Italian student said: “during dissections, the professor was judging their reactions in front of a cadaver and this was some kind of an ordeal.”

Other techniques are used to reify the corpses, such as dividing up of the body. This can be done virtually (to stand behind fellow students, to cover the rest of the corpse with cloth as during operations);8 theoretically (to imagine sketches, to divide the body in regions, organs, systems . . .); or actually (to dissect a zone). Yet that process of reification meets resistance: some body parts are not easily “anatomizable”: faces and hands are usually hidden during dissections.3,7,11

The manipulations of dead bodies to change them into “anatomies” serve the objectives of practical education. However, other images follow the breaking of the humanity of those beings and lead students into territory not directly related to the acquisition of medical competencies. The transformation of corpses into meat, shown through slang words meaning “meat” used to name them in France, allows students to reify them, to dehumanize them through an animalization that legitimates or at least excuses the violence done to them.14 References to a symbolic anthropophagy are not rare either, in gestures, comments, or practical jokes. For example, this scene, observed at the end of a dissection in Toulouse: Surrounded by other medical students, two students fought for the prerogative to hold the scalpel and cut the body. “Who wants some liver? Bon appétit. Come see the liver! It looks like foie gras (goose liver pâté) . . .” Suddenly, one of them, dissecting pliers in one hand, grabs the other’s surgical knife with his other hand, and handling his tools like macabre cutlery, leans towards the open thorax with a hungry look. It seems that breaking the taboo of opening the human body stimulates thoughts about violating the taboo of cannibalism, with one infamy bringing on the other.13

About five centuries earlier, after a week of dissection, Thomas Platter, a middle-age Dutch medical student who went around France and Europe with his brother during his medical studies, wrote in his diary that he had dreamt he had eaten human flesh and had woken up in the middle of the night to vomit. On both sides of the Atlantic, stories are told about lay people or students unwittingly eating pieces of corpses thrown in the soup by other students.15

As a difficult victory over their disgust, the so called “meat fights” stories, circulated in France until the middle of the XXth century, in which students depict themselves or others “cutting the meat and throwing it at each other” during dissections, are the first spectacular evidence of the acquisition of manners that establish belonging to the medical profession, through a combination of disgust and liberating laugh.

Yet, vast differences are seen in how students engage in a similar experience. From the first dissections onward, around the table, a concentric organization is created, based on a hierarchy among actors, giving all the opportunity to participate in the collective ordeal. Those in the center who go too far and those in the rear who criticize others break implicit rules, yet participate in the experience. Female students have tended to be more passive and end up being the target of jokes—mostly obscene—made by their male counterparts, who view the dissections as a challenge and an opportunity to show-off. In a vast corpus of “cadaver stories” collected in the 80’s by an American anthropologist, Hafferty, some stories feature students cutting the penis of one cadaver to put it in another cadaver’s vagina, to shock female students, but in the more recent accounts, women play a more active role.15

The anatomy lesson

This eruption and performance of violence, obscenity, and blasphemy do not capture all we observe during dissections. Opposed to such transgressions, paradoxically, other gestures and behaviors seem similarly necessary, echoing the paradox and ambivalence of those necessary as well as un-useful dissections.

In France, the first dissection is not preceded by official discourses on the respect of the sacred status of the dead, as in Italy or the US.3,7 Students from Toulouse follow implicit rules that organize and limit even behaviors that seem uncontrolled. The first ones to criticize the violent behavior occasionally displayed by their classmates are those for whom dissections were hard to stand: “I am shocked because no respect is shown to Death.” Students perceive the need to limit what can from what cannot be done, the licit from the illicit.

Many behaviors may be observed during dissections that help define what students mean by respect. One turns around to sneeze, one says “sorry” when touching a corpse by chance, and one whispers next to corpses. Teachers and students use the word “patient” or “sick person” instead of corpse, and American students call themselves doctors and say “surgery” instead of “dissection.”8 The stillness of those lying bodies, tucked in their shrouds with eyes closed, turns those scary beings into quiet sleepers. Inviting a group of students to enter the lab, an assistant joked: “don’t worry, I’ve given them a sleeping pill!”

To respect corpses is first to admit their irreducible humanity. This is done throughout a series of queries that aim to give them a social identity. Students want to know age, medical history, causes of death, and life stories of their “patients.” Some American teachers recommend providing such information to (re)personalize the corpse and help students to remember that those people have lived before. To make “their” dead more familiar, some US students give the cadaver a name, or even carve them with their initials.8 In a medical school in Chicago, students have to write a biographic piece about the cadaver they are dissecting.

Identity can be given back more spontaneously yet more disturbingly through recognition. For example in Toulouse, two students said they believed they recognized their own grandparents. American students tell stories about removing the face cloth from a corpse and realizing with horror that it is someone from their immediate family.9 This recovered humanity raises questions about the students’ own identity. If in corpses you see your own ancestors, does that not imply you belong to the same kind and same destiny? This helps to understand the uneasiness of students about dissecting bodies of young people. Though young corpses are more interesting to dissect, identification with them would be too close for comfort. This may also help explain the disinclination of medical students to donate their bodies to science.9,13

In the corridors of the lab, I saw a worried male student trying to make a female student smell his neck just after his first dissection. This smell is the first characteristic of the corpse. He or she who breathes it becomes impregnated with it: “I have a friend who, afterwards, always smelt his hands . . .” Smell is the first evidence of the transformation of the students. Medical books on occupational disease in the nineteenth century describe the sweat, urine, and feces of anatomists as being impregnated with putrid miasmas that were seen as a main danger for doctors, together with poisonous infections that killed many of them.

The ordeal of intimacy with corpses forces students to see death, to overcome it more easily, but also to skim it, to face its danger. Today, when antiseptics and antibiotics help control the risks of septicaemia, teachers still give the same recommendations: “Be careful, don’t cut yourselves!” pompously changed by this impressed student: “With the slightest cut, you’re dead!”

Confronted with those threatening beings, the risk is to pass on deaths’ side. Pushing the lab door is passing into the other world, so as to directly experience its properties. As a physician interviewed about dissection said: “one can carry on medical studies only when one has accepted one’s own death. That is when one has visualized it.” The ordeal is to be stronger than the horror of the corpses who, in traditional representation, often reach out to bring the living along with them. One young French student interviewed in Toulouse repeated a horrific story about students who put a leg from a cadaver in the bed of a friend who awoke and died of shock. A psychiatrist reported 40 years later having had repeated nightmares about dissections: “I am one of those who almost gave up medicine because of the corpses! [. . .] I still clearly remember this dream. The corpses were after me. I would jump through windows, run, go up the stairs, and they were after me. They wanted to get me. I had this dream many times, I had been deeply shocked.”

One can better understand those “meat fights” and other cannibalistic dramatizations as a means of incorporating death; somehow, through these “rituals,” students obtain the double power of both coming back different to the world of the living and being better able to cure those whom illness takes temporarily into the other world.

Consecrations and testimonies

Even if invisible and symbolic, a transformation is felt by those who undergo it. About his first dissection in the 1960s, a French surgeon said, “I see people walking outside, and I told myself: actually, you are not one of them, they are lay people, you are a scholar. They will never understand what you do. You belong to another world, and you know things they’ll never know.” In other words, anatomical knowledge, throughout the dissection experience, has turn him into an “initiated.”

And as all initiated do, medical students, proud to have overcome this first ordeal, want to show their new status. Family, friends, and younger students have to listen to terrible stories, preferably during meals. But while doing this, medical students just act as is expected by the rest of society, which perceives them to be keen on dissecting corpses for hours.

These stories that force others to undergo the same ordeal are not the only consecration of this new knowledge. In the 1960s, in Toulouse (France), a professional photographer came to take pictures in the anatomy lab around a corpse, as he would do for school classes and other organized social events—such pictures can be found since the XIXth century. The created image ceremonially honored this transition. The tradition vanished, yet I was given similar pictures from the late 1970s—but informal, provocative pictures, taken by a student during dissections. The woman who showed them to me laughed when telling me they were exposed in her student room, just for fun; like the professional photos, this woman’s photos played the same role as provocative stories: a proof of undergoing successful transformation.

Conclusion

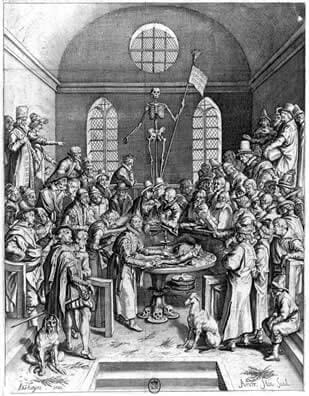

Through dissection, contemporary medical schools still provide a paradoxical experience through which students obtain knowledge about death in a manner that is quite unusual for modern medicine. The same duality existed during the Renaissance.16,17 The frontispiece of anatomy books from the time of Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) is divided into two parts: below, the corpse, which is being dissected by professors and students and is surrounded by a crowd trying to see; and, above, the skeleton with the scythe (see image above). Thus, in a time where it seemed the anatomy lesson was de-ritualized to become a way to have access to positive knowledge good for all, a symbolic dimension was reintroduced: death, personalized by its skeleton and accessories.

Since the end of the eighteenth century, dissections have become the privilege of medical doctors, their first ordeal, with a symbolic efficacy that has never failed. In the customary logic that drives this moment, scientific and academic logic is undermined: so to make the humanity of the corpses disappear, the students try to see only an anatomy, a wax body, or even some abstract sketches. One can hypothesize that this superposition of the academic and customary logic contributes to the professionalization of the senses, opened by the paradigmatic experience of dissection.

Behind the doors of the anatomy lab, the ordeal of dissection separates forever those who will become doctors from those who will not, those who have managed to control their senses from those who did not succeed, those who have overcome the horror of death from those who have not been confronted with it and never will be, at least not as a doctor.

Notes

- For a first analysis of dissections as right of passage for medical students, see work cited #18.

- When no precision is given, the citations and comments are from French students or practitioners, interviewed by the author for her PhD. All citations are given in quotation marks.

- Dr. Gonzalez-Crussi in “Anatomy lessons, a vanishing rite for young doctors,” New York Times, 23 March 2004.

- Such software is available in many countries and usually given access to students in the medical library. They are usually linked to the visible human project. See: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/visible/visible_human.html

- In this I refer to Goffman’s analysis of negative experiences (see work cited # 19).

Works Cited

- GODEAU E. «L’ esprit de corps. » Sexe et mort dans la formation des internes en médecine. [L’« esprit de corps ». Sex and death in the training of medical residents]. Paris: Editions de la maison des sciences de l’homme, 2007.

- BENNETT SWINGLE A. “Four students and a cadaver.” Hopkins Medical News Spring 2000.

- BOURGUET CC, WHITTIER WL, TASLITZ N. “Survey of the educational roles of the faculty of anatomy departments.” Clinical Anatomy 10 (1997): 264-271.

- DYER GSM, THORNDIKE MEL. “Quidne Mortui Vivos Docent ? The evolving purpose of human dissection in medical education.” Academic Medicine 10(75) (2000): 969-979.

- DICKINSON GE, LANCASTER CJ, WINFIELD IC, REECE EF, COLTHORPE CA. “Detached concern and death anxiety of first-year medical students : before and after the gross anatomy course” Clinical Anatomy 10 (1997): 201-207.

- FERRARI G. “Public anatomy lessons and the carnival: the anatomy theatre of Bologna” Past and Present 117. (1987): 50-106.

- FOX R. Essays in medical sociology. New-Brunswick, Oxford: Transaction Books, 1988: 51-77.

- SEGAL D. “A patient so dead : American students and their cadavers.” Anthropological Quarterly 1 (61) (1988): 17-25.

- HAFFERTY F W. Into the valley – Death and the socialization of medical students. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1991.

- DINSMORE CE, DAUGHERTY S, ZEITZ HJ. “Teaching and learning gross anatomy : dissection, prosection, or « both of the above » ?” Clinical Anatomy 12 (1999): 110-114.

- ABU-HIJELH MF, HAMDI NA, MOQATTASH ST, HARRIS PF, HESELTINE GFD. “Attitudes and reactions of Arab medical students to the dissecting room.” Clinical Anatomy 10 (1997): 272-278.

- FRANCIS NR, LEWIS W. “What price dissection ? Dissection literally dissected, J Med Ethics.” Medical humanities 27 (2001): p. 2-9.

- SINCLAIR S. Making doctors. An institutional apprenticeship. Oxford – New York: Oxford International Publishers, 1997.

- BURGAT F ; in HERITIER F. ed. La logique de la légitimation de la violence : animalité vs humanité, De la violence II. [The logic of the legitimisation of violence : animality vs. humanity, About Violence II]. Paris: Odile Jacob, 1999: 45-62.

- HAFFERTY F W. “Cadaver stories and the emotional socialization of medical students.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 29 (1988): 344-356.

- CARLINO A. La fabrica del corpo. [The creation of the body]. Torino: Guilio Einaudi, 1994.

- CARLINO A. “Entre corps et âme, ou l’espace de l’art dans l’illustration anatomique, [Between body and soul, or the space of art in anatomical illustrations],” Médecine/Sciences Vol 17( 2001): 70-80.

- GODEAU E. « Dans un amphithéâtre… » – La fréquentation des morts dans la formation des médecins [« Dans un amphithéâtre… »- The frequentation of death during medical training], Terrain. 1993 ;20: 82-96.

- GOFFMAN E. Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. London: Harper and Row, 1974.

EMMANUELLE GODEAU holds degrees in medicine and social anthropology. She works as a public health medical doctor for the Service Médical du Rectorat in Toulouse (Ministry of French national education) and as a researcher in the medical research unit Inserm U558, on health and disabilities of children and adolescents. Her anthropological research is focused on death, contemporary professional trainings and their feminization. She is a member of the Centre d’ Anthropologie Sociale in Toulouse.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 1, Issue 5 – Fall 2009