|

|

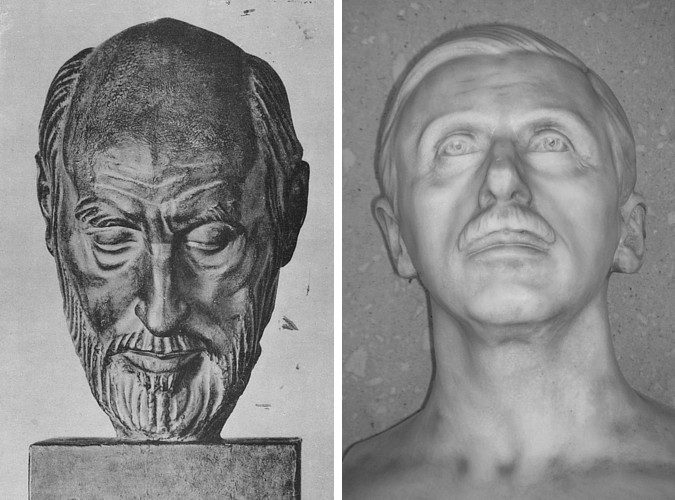

Figure 1. (Left) Marble bust of Ramón y Cajal. Royal National Academy of Medicine in Madrid, reproduced from a period postcard. (Right) Marble bust of Constantin von Economo. Arkadenhof of Vienna University, crafted by Max Kremser from an actual cast with the Alphons Poller technique. Author’s archive. |

Lazaros Triarhou

Thessalonica, Greece

Two visionaries of biomedicine, Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934), “the father of modern neuroscience,” and Constantin von Economo (1876-1931), “a passing meteor in the firmament of neurology,” made major discoveries in neuron biology, cerebral cytoarchitecture, and human neuropathology.1,2 Their surnames are carved into eponyms, including “Cajal cells” and “von Economo encephalitis.” Cajal was awarded the Nobel Prize (jointly with Camillo Golgi); Economo was nominated for the summa cum laude of the Swedish Academy.

Their era witnessed the advent of the bicycle, the typewriter, the telephone, electricity, the automobile, and the airplane. It was in their lifetime that science harvested fruits begotten by the laboratory revolution of the 1860s. They also witnessed the “Great War.”

There are parallels in the lives of the two men. Both explored the mind through a microscope and drew nerve cells via a camera lucida. They lived by the altruism common in their heyday. And they exchanged correspondence.3

There are also differences. I next highlight antipodal opinions that the two anatomists expressed regarding the conquest of speed by engineering. For the nostalgic Cajal, the transition from the horse to the automobile and the flying apparatus was a dangerous endeavor. For the technically-minded Economo, the conquest of gravity was a step forward in the path of humanity’s evolution.

The frenzy of velocity

On May 25, 1934, Cajal published his Impressions of an Arteriosclerotic, an attempt at clarifying age’s problems for the laity.4,5 In one chapter, under the present subheading, Cajal expressed his displeasure for the airplane, which he considered a deplorable obsession and a dangerous contraption.6,7 Here is an excerpt:

Innumerable writers have deplored this dangerous mania of our times. Humanity seems determined to eliminate distance. We used to explore the terrain travelling on horse, in carriage or accelerated galley, get ecstatic before the picturesque landscape, historical ruins, breath the fragrant atmosphere of forests and orchards, rest in busy inns and reanimate numb limbs over logs of the traditional fireplace! All this has passed to history. We now arrive as early as possible where no one expects us; we ignore the road; we cohabit with disdainful, moody and idler gentlemen; we are condemned to silence for long hours, swallowing dust and soot …

As if the train was not enough to satisfy the crazy urge for dizzying speed, the miracle of Yankee and French mechanics emerged: the car…We have become preoccupied with the purchase of car models, lubricants, gasoline, tires, licenses, and endless taxes. We are concerned with the selection of a chauffeur, in whose sinful hands and brain (not always alcohol-free) we entrust our life and that of our loved ones.

The advances in engineering produced a victim that no one talks about: the noble horse, whose disdain will ultimately extinguish the equine race. Perhaps track betting will somewhat delay the thoroughbred’s annihilation. Like zoological species, the inventions of civilization hatch, triumph, decay and expire, only to be replaced by other mechanisms, more refined and almost always more lethal.

The automobile produced unexpected moral effects in big cities…Poor children, elderly and distracted, sacrificed victims of progress and useless velocity! And poor engulfed poets and thinkers! … But the most unpleasant aspect of the automobile is the sleight of the landscape. Acceleration suppresses the enchantment of contemplation. We must resign to ignoring the road, travel like packages among clouds of dust and parades of menacing trees.

The automotive artefact is a despicable machine. The slightest shock deteriorates it, and it has to be rebuilt and renewed every four to six years. We converted the roads, which were designed for carriages and horses, into race tracks; and the road has avenged our imprudence by causing all types of tragic accidents.

In the early days of motoring, donkeys and horses, terrified before the advance of the formidable artefact, would quickly turn towards the curb or stray into the row of adjacent trees to escape the absurd projectile, guided by the infallible instinct of danger. To no effect, the prudent solipeds explored the front of the vehicle to discern the horse. Accustomed now to our recklessness, they are no longer scared — unequivocal proof that they learn. Through willpower they bridled their reflexes and acquired a sangfroid that we would wish to have. A modality of “conditioned reflexes,” as Pavlov would say.

The automobile was not enough to satisfy the irrepressible craving for acceleration. First a couple of Americans, then the French, launched a new extremely dangerous toy: the homicidal aeroplane. Bold and fearless in war, it is as scary in peace…This new Moloch of applied science slaughters hundreds of victims annually. I know of no active aviator who has reached age 50. They all die in accidents, and the funny thing is that no nation lacks candidates for violent death. It is so graceful to hover in the clouds and admire the earth as a two-dimensional miniature, to feel the jolt of “air-bumps” and to pity the miserable rampants, like ants at ground level …

Haunted by the demon of velocity, life lost much of its value. Above all, life lost that peace of mind, which is so compatible with the aesthetic pleasures of landscape. One dies with the same unconsciousness with which one is born, but faster, without agony. The human organism, whose formation and education costs 25 years, is destroyed instantly. In a flash, it turns into an amorphous mass of physicochemical protoplasm.

From this brutally realistic perspective, combustion engines can be considered regulatory instruments of demography. Thanks to them, population figures are maintained within prudential limits. The Manes of Malthus [deities that represent the souls of the dead in the Essay on the Principle of Population] would smile satisfied, seeing how scientific industries automatically diminish the overabundance of banqueters waiting for their turn at the dinner table, increasingly less stocked, from social subsistence.8

Usque ad astra!

|

|

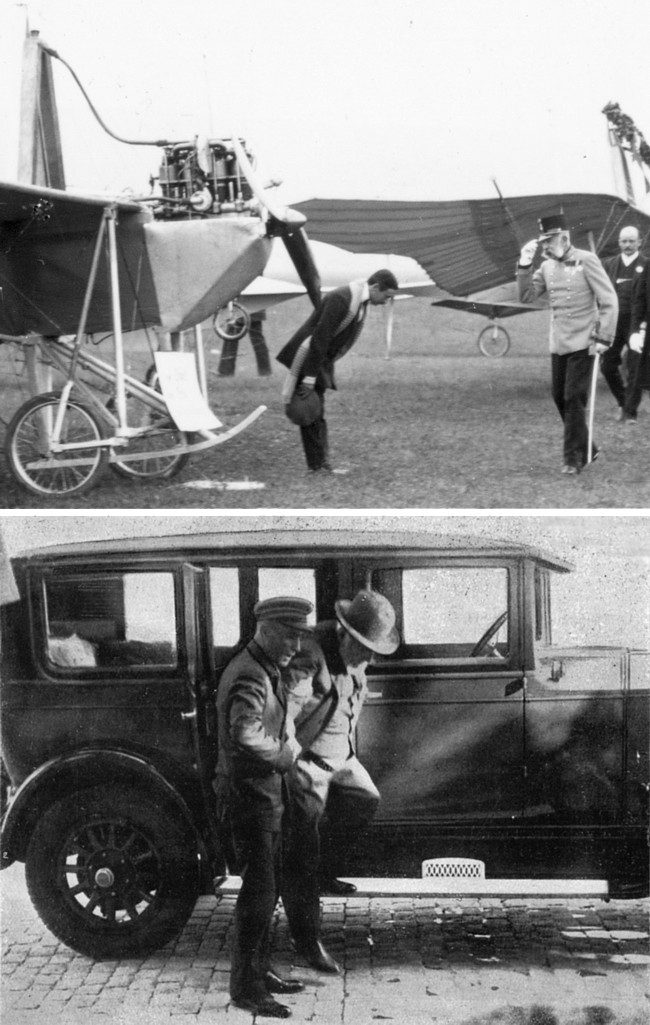

Figure 2. The Celestial and the Terrestrial (Upper) Baron von Economo with his Etrich-IV Taube monoplane, saluted by Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary at the Wiener Neustadt airfield (9/18/1910). (Lower) Prof. Cajal stepping out of his Panhard & Levassor near Calle Montera, Madrid. Photo by Palomo for Blanco y Negro (10/21/1934). Reproduced for the Diario Ilustrado ABC (5/3/1952). Author’s archive. |

In 1907, with the historic flight of the Wright brothers still fresh, the youthful Economo became interested in aeronautics.9,10 He purchased a Voisin biplane in Mourmelon-sur-Marne and an Etrich Taube aircraft in Vienna. Economo was the first Austrian to obtain an international pilot’s diploma and was field-pilot no. 7 of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; he presided over the Austrian Aero-Club for sixteen years and served as chairman of the Aviation Board at the Austrian Ministry of Commerce and Transport.10,11 In 1918 he published a memorandum on the conditions and the necessity of promoting air traffic.12

In 1927, on concluding the active presidency of the Aero-Club, Economo responded to his successor as follows:

Comrades! It is a time rich in hopes, disappointments and beautiful fulfillments, full of memories of a glorious development, begun with the adventurous ascent in the spherical balloon and continued to the recently accomplished flights over sea and land. The millenia‑old envy of man at the flight of birds and the drift of clouds has found form.

God, or Nature, or whatever else you wish to call the mysterious creative force of this world, which in the course of millions of years in the scale of phylogenetic evolution created out of the simple cell all the diverse and ever more complex forms of life, and continues to perfect them, has, of all living things on this earth, endowed only man with the capacity to create new things. And while in the animal world, for example, the creative power of birds is limited to building the same nest over and over, or of bees to the unchanging design of the honeycomb, Creation impressed part of its creative craft upon the human brain, enabling us to create anew and to achieve increasingly higher possibilities along the way of our ascending evolution. And so it is this same creative force of Nature, which in the course of eons gave the eagle its flight, that in recent decades enabled us humans to construct wings and overcome the ties of gravity that bind us to the earth. Such endeavors come to expression in part consciously, in part unconsciously, as an idea or as a brooding urge, in this instance as the ancient longing, ever-recurrent in dreams, to fly through space, freed from the chains of gravity.9

Economo had a deep insight into physics and studied the newly formulated theory of relativity.9 At the celebration of the 30th anniversary of the Aero-Club in March 1931, Economo foresaw space flight:

Calculation shows that, to lift a body to regions in space beyond the gravitational pull of our earth, it would require a wholly terrific amount of explosive material, several thousand times the mass of the body in question. Modern physical research shows that once we have a means of mastering the disintegration of atoms, it will be possible to transcend the force of gravity. Those who then as worthy sons of the Titans make these first journeys will be of the same stuff as their predecessors who conquered the air, and from the ranks of the conquerors of the air will advance these stormers of the heavens.

Clear to the stars!9

Envoy

Thus Baron von Economo envisaged travel in space. However, it was Cajal’s glass slides, and eight of his ink drawings, that defied gravity and hopped a ride aboard NASA’s Columbia Space Shuttle during “Mission Neurolab STS-90” on April 17, 1998.13 Coincidentally, that day marked the eighty-first anniversary of Economo’s lecture before the Viennese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology, and the historic presentation of a new entity termed encephalitis lethargica.14

References

- DeFelipe J. Sesquicentenary of the birthday of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the father of modern neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:481-484.

- Théodoridès J. Constantin von Economo (1876-1931) savant, humaniste, homme d’action. CR Congr Int Hist Méd. 1966;19:624-636.

- Santarén JAF. Santiago Ramón y Cajal: Epistolario. Madrid: La Esfera de los Libros; 2014.

- Ramón y Cajal S. El mundo visto a los ochenta años: Impresiones de un arteriosclerótico. Madrid: Tipografía Artística; 1934.

- Historical section. Gerontologist. 1968;8:54-55.

- Ramón y Cajal S. Der Rausch der Schnelligkeit (transl. by H. Draws-Tychsen). Die Fähre. 1947;2:635-637.

- Hoare MR. Ramón y Cajal’s testament to old age. Rev Clin Gerontol. 1998;8:163-171.

- Triarhou LC. Cajal beyond the Brain: Don Santiago Contemplates the Mind and Its Education. Thessalonica – Indianapolis: Corpus Callosum; 2015:170-176.

- Schönburg-Hartenstein von Economo K, Wagner von Jauregg J. Baron Constantin von Economo: His Life and Work (transl. by R. Spillman). Burlington, VT: Free Press Interstate Printing Corp.; 1937.

- van Bogaert L, Théodoridès J. Constantin von Economo: The Man and the Scientist. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften; 1979.

- Fischer I. Biographisches Lexikon der hervorragenden Ärzte der letzten 50 Jahre, Bd. 1. Vienna: Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon; 1932.

- von Economo CJ. Memorandum betreffs des derzeitigen Standes und der notwendigen Förderung eines Luftverkehres. Mitteil kk Österr Aëro-Club. 1918;5:150-160.

- Nombela Cano C. Misión Neurolab, CSIC – NASA, Abril 1998. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas; 1998.

- von Economo C. Encephalitis lethargica. Wiener Klin Wochenschr. 1917;30:581-585.

LAZAROS C. TRIARHOU, MD, PhD is Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Macedonia in Thessalonica, Greece. After graduating from the Aristotelian University School of Medicine, he pursued graduate studies in the Center for Brain Research of the University of Rochester, New York, and the Neuropathology Division of Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, where he also served on the faculty for a dozen years before returning to his native Greece. He is the recipient of the Bodossakis Foundation Science Prize in Medicine. He has authored over 150 papers in Neurobiology and written or edited 30 books.

Leave a Reply