Shameemah Abrahams

South Africa

The year 1945 is iconic as the end of one of the most pivotal and devastating periods in human history—World War II. That same year, as the world began to rebuild, in the coastal city of Cape Town at the tip of Africa, a young medical graduate began what would become an esteemed and memorable career in medicine.

The renowned late cardiac surgeon Christiaan Barnard (1922–2001), born in the arid Karoo town of Beaufort West, started his medical career in tuberculosis meningitis. Only after obtaining his Masters and Doctorate of Medicine degrees (1953) was he exposed to cardiac medicine, as he pursued postgraduate training at the University of Minnesota and became acquainted with heart surgery pioneers Walt Lillehei, Norman Shumway, and Richard Lower.1 At the time, Shumway and Lower were developing techniques (such as orthotopy) necessary to perform heart transplantation in humans.2 And so the race began to make medical history, by successfully performing the first human-to-human heart transplant.

One of the most prolific moments in Barnard’s career, catapulting him to world fame amidst a troubled apartheid South Africa, was set at the Groote Schuur Hospital located near the base of Table Mountain and linked to Cape Town’s oldest medical school, the University of Cape Town’s Faculty of Medicine. On December 3, 1967, assisted by a team of thirty including his brother, Dr. Barnard successfully transplanted the heart of car accident victim Denise Darvall into 53 year old Lewis Washkansky, who unfortunately died eighteen days later from graft rejection.3 Although cardiac pioneers Shumway and Lower developed the essential cardiac surgical techniques, Barnard took the potentially fatal and seemingly impetuous risk in the already-notorious field of heart transplantation. His unwavering conviction of a successful transplant was possibly aided by his practical perspective of the topic as reflected in his comment on why patients elect heart surgery: “for a dying person, a transplant is not a difficult decision. If a lion chases you to a river filled with crocodiles, you will leap into the water convinced you have a chance to swim to the other side. But you would never accept such odds if there were no lion.“4

However, above and beyond his human-to-human heart transplant success, his role in “individualized post-operative care” to reduce the likelihood of mortality after heart surgery may have played an even greater role in revolutionizing cardiac medicine.4–6 This pioneering concept of postoperative intensive care seemed to garner success with some of Barnard’s patients surviving more than a decade.7 He was also known for his contributions to treatment strategies for heart conditions such as endocarditis, tetralogy of Fallot and Ebstein’s anomaly, as well as the development of an artificial aortic valve.8–11

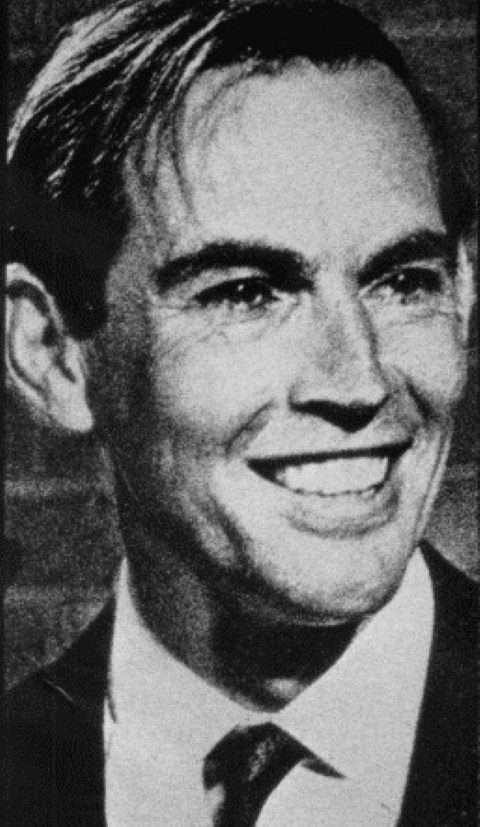

Barnard was renowned in the scholarly world of medicine and also in the general public. His rise from poverty-raised South African to lauded surgeon along with his charisma, charming good looks, and also his infamous extramarital affairs made for an intriguing life story. After rheumatoid arthritis forced him to give up his surgical career, he remained in the public eye as he continued to write scientific and autobiographical books, founded the Christiaan Barnard Foundation to aid disadvantaged children and even controversially endorsed an anti-aging cream that was quickly discredited by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1,12–15 At the ripe old age of 78, medical pioneer, cardiac surgeon, author, and celebrity Dr. Christiaan Barnard, contrary to popular belief at the time, did not die from cardiac failure but as a result of a severe acute asthma attack while vacationing in Cyprus.16

Thirteen years after Barnard’s death, his medical achievements and endearing persona ensured a lasting memory of a pioneering cardiac physician from the Karoo. Beyond that, his life work has promoted and inspired past, current, and future physicians to push the boundaries of medical innovation and become world contenders in cardiology and all other branches of medicine.

References

- McRae D. Every second counts: the race to transplant the first human heart. New York: GP Putnam’s Sons; 2006.

- Lower RR, Shumway NE. Studies on orthotopic homotransplantation of the canine heart. Surg. Forum. 1960;11.

- SAHO. Dr Chris Barnard performs the world’s first human heart transplant, South African History Online. South African Hist. Online. Available at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/dr-chris-barnard-performs-worlds-first-human-heart-transplant. Accessed November 8, 2013.

- ZAR. Biographies: Christiaan Neethling Barnard, updated January 2007. Available at: http://zar.co.za/barnard.htm. Accessed November 8, 2013.

- Barnard CN, Dewall RA, Varco RL, Lillehei CW. Pre and Postoperative Open Care Cardiac for Patients Undergoing. Chest. 1959;35(2):194–211.

- Barnard CN, Losman JG. Left ventricular bypass. S. Afr. Med. J. 1975;49(9):303–12. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/410998.

- Barnard CN, Cooper DK. Clinical transplantation of the heart: a review of 13 years’ personal experience. J. R. Soc. Med. 1981;74(9):670–4.

- Croft CH, Woodward W, Elliott A, Commerford PJ, Barnard CN, Beck W. Analysis of surgical versus medical therapy in active complicated native valve infective endocarditis. Am. J. Cardiol. 1983;51(10):1650–1655.

- Barnard CN, Schrire V. The surgical treatment of the tetralogy of Fallot. Thorax. 1961;16:346–55.

- Charles RG, Barnard CN, Beck W. Tricuspid valve replacement for Ebstein’s anomaly. A 19 year review of the first case. Heart. 1981;46(5):578–580. doi:10.1136/hrt.46.5.578.

- Beck W, Barnard CN, Schrire V. The Hemodynamics of the University of Cape Town Aortic Prosthetic Valve. Circulation. 1966;33(4):517–527. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.33.4.517.

- Hacker K. From A Cream, A Dream Of Youth Christiaan Barnard Uses What He Promotes, But Is That Why He Looks So Young At 63? Inquirer. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/1986-03-04/entertainment/26081581_1_first-heart-transplant-skin-trade-creme. Accessed November 30, 2013.

- Sloan P, Freeman L. FDA plans to expand crackdown to skincare product advertising. Advert. Age. 59(15):12.

- Sloan P, Freeman L. Skincare “drug” claims challenge FDA. Advert. Age. 59(40):80.

- Sloan P, Freeman L. FDA ready to slap skincare claims. Advert. Age. 59(43):73.

- Autopsy confirms asthma killed Barnard. Cyprus Mail. Available at: http://web.archive.org/web/20070927202905/http://www.cyprus-mail.com/news/main_old.php?id=4655&archive=1. Accessed November 30, 2013.

SHAMEEMAH ABRAHAMS, BSc (Med) Hons, majored in Biochemistry and Physiology for her BSc (2008–2010) with honors in Physiology (2011) at the University of Cape Town (UCT). She is currently pursuing a PhD at UCT and her supervisors are Dr. Michael Posthumus and Dr. Alison September. Her project aims to identify both non-genetic and genetic predisposing factors of concussion risk in South African schoolboy rugby and geared towards investigating the underlying physiological mechanisms increasing susceptibility to concussion. Her research interests include brain injury, physiological changes during exercise, and genetic predisposition to injury.

Leave a Reply