Gregory Rutecki

Cleveland, Ohio, United States

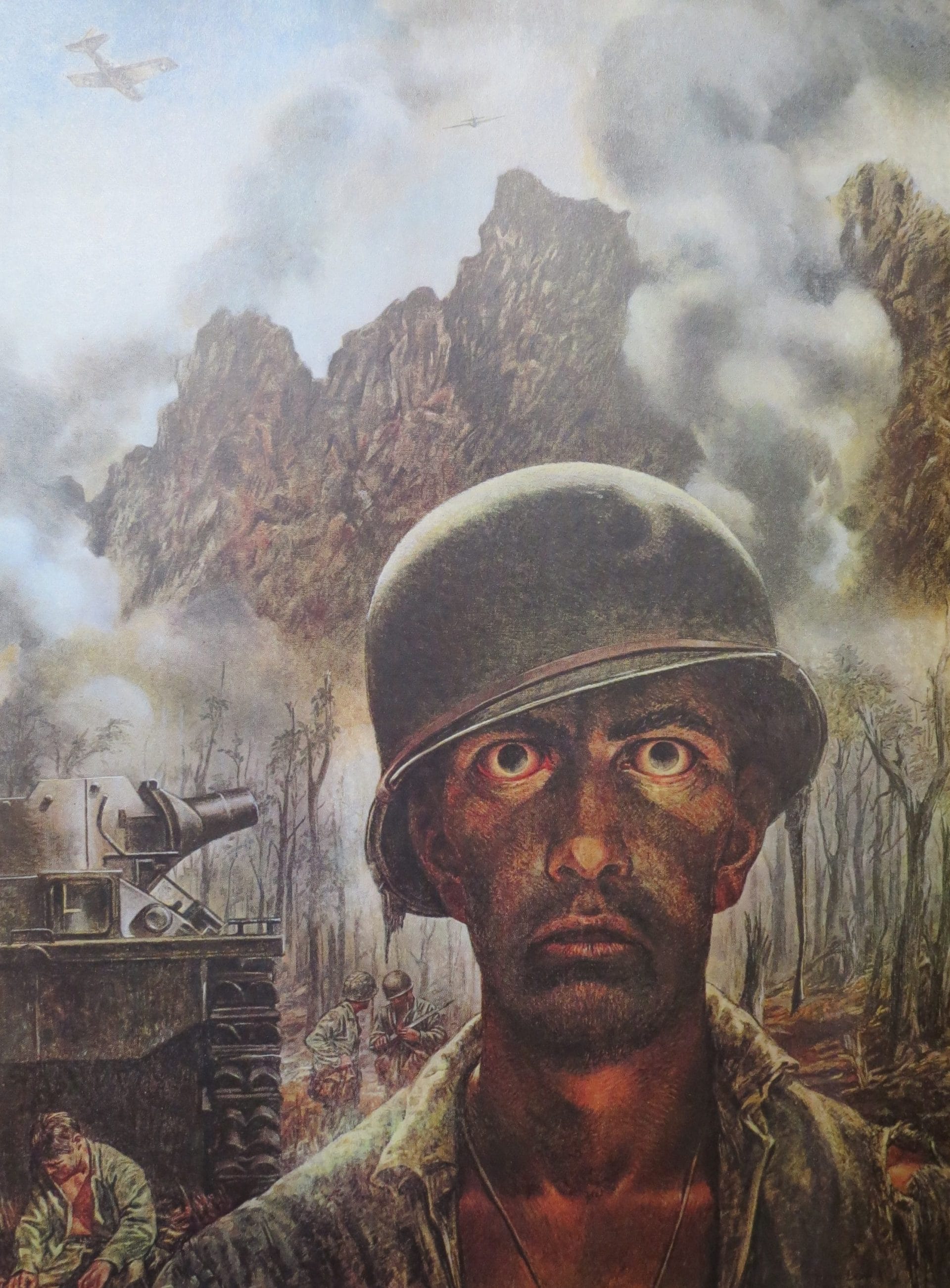

“I noticed a tattered marine…staring stiffly at nothing. His mind had crumbled in battle…his eyes were like two black empty holes in his head…Last evening he came down out of the hills. Told to get some sleep, he found a shell crater and slumped into it…First light has given his gray gray face eerie color. He left the States 31 months ago. He was wounded in his first campaign. He has tropical diseases…He half sleeps at night and gouges Japs out of holes all day. Two thirds of his company has been killed or wounded…How much can a human being endure?” —Tom Lea’s comments on his painting The Two Thousand Yard Stare1

“It [World War Two Pacific warfare] was an existential struggle of annihilation…killing was fueled by political, cultural—and racial—odium in which no quarter was asked or given: ‘a brutish primitive hatred as characteristic of the horror of war in the Pacific as the palm trees and the islands.’”2

What has evolved into post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was suspected before the twentieth century. In 1678 Johannes Hofer wrote about Swiss mercenaries who were dejected, insomniac, and anxious.3 He observed that if these individuals were not sent home, they “died or went mad.” Since the advent of two World Wars with carnage on unprecedented scales, symptoms such as cold sweats, stomach problems, crying, and anger have been added to the syndrome.3,4 One often-mentioned sign of battle fatigue—the 2000 yard stare (refer to Image 1)—is of World War Two vintage. It is the personal testimony of an artist, Tom Lea, present at the World War Two battle of Peleliu. That bloody and almost forgotten battle combined every form of combat terror, catalyzing emotional reactions in combatants, and searing permanent scars on their psyches. Victims of that battle, with ongoing PTSD, included the Marines and Japanese who bitterly fought there, the corpsmen and physicians who treated their wounds, and the artist who painted the struggle.

Peleliu: WWII Pacific island of horror and death

“[The dead were] covered with ponchos to keep off the flies…[They] were a constant reminder of our mortality…decomposition was rapid…no one who has been in combat will ever forget the smell of death.”5

Peleliu represented a revolutionary change in Japanese war tactics.6 The Imperial Army would now embrace the doctrine of attrition. The Japanese defenders of Peleliu were ordered to “butcher Marines…to dig deep…infiltrate and counterattack…[there were] 500 cunningly located coral caverns…stocked with food and ammunition…there were 10,700 such Japanese waiting, all prepared to die.”6 Because of dense tropical vegetation, aerial reconnaissance was useless. The Japanese defenders constructed four to five story caves capable hiding hundreds of men.5 There would be nowhere to hide, digging foxholes in the coral was impossible.6 The ridge of a mountain in Peleliu, Umurbrogol, “had become a monstrous thing. Wounded men lay on shelves of rock, moaning or screaming as they were hit again and again. Their comrades fell and tumbled past them.”6 Twenty-six American Amtraks in the first wave were burned before they landed.7 The incinerated marines were rendered “black as toast,” still upright though dead, but holding their weapons.5 Marine casualties would be double those at Tarawa.2 Taking Bloody Nose Ridge—the Marines’ nickname for Umurbrogol—cost more lives than the landing at Omaha Beach.8

One battalion lost 70% of its men, the greatest number of casualties for a single unit in Marine Corps history.5 In Eugene Sledge’s book, With the Old Breed, two vignettes capture the terror of combat at Peleliu. First, he describes his own response to artillery without the shelter of a foxhole: “During prolonged shelling, I often had to restrain myself and fight back a wild, inexorable urge to scream, to sob to cry…if I ever lost control of myself under shell fire my mind would be shattered…[shells] tortured one’s mind almost beyond the brink of sanity.”

The second vignette concerned a marine who broke under fire. “The poor marine had cracked up completely. The stress of combat had finally shattered his mind…he screamed more loudly…he fought like a wildcat, yelling and screaming at the top of his voice…morphine…had no effect…the noise would announce our exact location to any enemy…[it was suggested that he be hit] with the flat of that entrenching shovel”!2 At morning’s first light that marine was found dead from the shovel’s trauma. A macabre twist on friendly fire.

Sledge also corroborates Tom Lea’s images of shell-shocked marines at Peleliu: “During the latter phase of the campaign the typical infantryman wore a worried, haggard expression on his filthy unshaven face. His bloodshot eyes were hollow and vacant from too much horror and too little sleep….overall he was stooped and bent by general fatigue and excessive physical exertion.”2

Medical care under extreme duress: The doctors and corpsmen of Peleliu

Peter Baird wrote a novel about his father’s service in the Pacific theater. Senior Captain Baird was a physician in the Army Medical Corps. The book was a novel, not a history, because Peter received no first-hand information from his father. His dad never told him about his experiences during the battle of Peleliu or how he received a wound to his left hand. The father-physician lost most of his surgical skills because of the injury. A 97-year-old uncle sent Peter letters written by his father that the son had never read: “Attached were 26 letters [by] Captain T.D. Baird…my father and these were letters he had written more than 60 years ago. [He] had been inexplicably wounded during the WWII battle of Peleliu and [the] wound…had traumatized him as well as his wife, son, and eventually, grandchildren.”9 His dad—a surgeon—returned a victim of battle fatigue and PTSD.

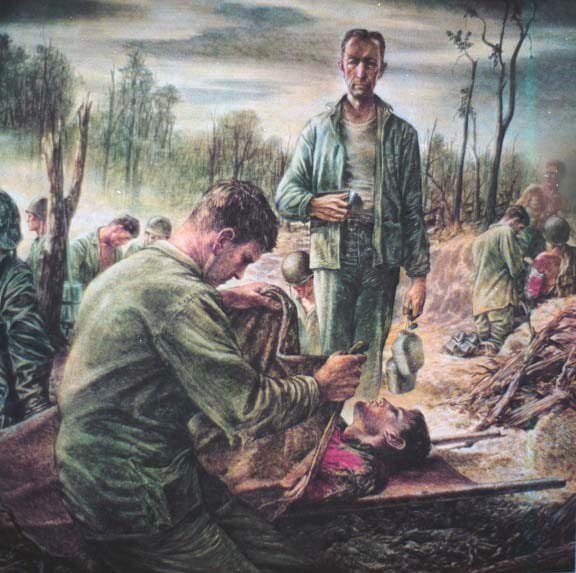

Dr. Baird treated 1,614 casualties. He performed surgery for 80 consecutive hours. During the battle, a sniper probably shot Dr. Baird’s left hand. He returned home a different man. He exhibited all the signs of PTSD. He and his family experienced his depths of depression, alcoholism, and anger. He would fly into harangues. He was prone to domestic violence and blistering spankings of his children.9 Peter Baird’s mother would only say “war had changed him.”9 In his father’s own words in the letters, “All surgery is done under fire and in field conditions…this is a holocaust…[I] did four amputations yesterday…broke down twice…more trauma surgery than I ever expected to do in my whole life…Must write sympathy letters.”9

On some days, surgery continued with the splashing of six inches of rain around the edges of the operating room. Primitive surgical conditions were a necessity at Peleliu. “Just behind the trench, in a large bomb crater surrounded by splintered trees, an improvised aid station had been set up. No hospital tent had been erected. That would have invited enemy fire. In the center of the crater a doctor was performing surgery, while corpsmen administered to the walking wounded.”8

The corpsmen’s job was dangerous. The Japanese prioritized them as targets. “The wounded crawled behind rocks or just lay motionless, bullets hitting them again and again. Others cried pitifully for help and begged their comrades not to leave them there…’medical corpsmen worked feverishly to drag the wounded out…one [corpsman] stood up…he too was killed.’”8

What hath war wrought? Ontological change in combatants

With the aforementioned, and myriad other experiences commonplace in combat, it is not surprising that soldiers, and their medical caregivers, return home fundamentally and permanently affected. The evolution from human to killer—or compassionate caregiver as witness to slaughter—begets permanent ontological and psychological devastations. Eugene Sledge himself said, “We all had become hardened. We were out there, human beings, the most highly developed form of life on earth, fighting like wild animals.”8

Discussing souvenir acquisition, which included gold teeth extracted from dying, but not dead persons, “Such was the incredible cruelty that decent men could commit when reduced to a brutish existence in their fight for survival amid the violent death…The fighting was savage, Neanderthal…its purpose was to inflict casualties and to wear us down…time had no meaning; life had no meaning. The fierce struggle for survival in the abyss of Peleliu eroded the veneer of civilization and made savages of us all.”8 But the pain does not disappear when survivors return. Sledge reflected, with reminiscences suggestive of his PTSD, “the increasing dread of going back into action obsessed me. It became the subject…of all ghastly war nightmares that have haunted me for many, many years…It occasionally still comes even after the…the violence of Peleliu has…been lifted from me like a curse.”2

Combatants return scarred at the very core of human existence. Sledge observed, “None of us would ever be the same after what we had endured…something in me died at Peleliu. Perhaps it was a childish innocence that accepted as faith the claim that man is basically good…We come from a nation…that values life…To find oneself in a situation where your life seems of little value is the ultimate in loneliness.”2 Ballads that condemn war and warn of its eternal recurrence—as in “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” and “The Green Fields of France”—predict future wars and the consequences of PTSD. In the words of Victor Davis Hanson, “There is a renewed timelessness to Sledge’s memoir…more relevant after September 11—war being the domain of an unchanged human nature and thus subject to predictable lessons that transcend space and time.”2 When counting the cost of war—for families, combatants, and medical/surgical caregivers—remember complete healing is a path, it may never be a destination.

References

- Lea T. (Ed. Brendan M. Greeley Jr.) The Two Thousand Yard Stare: Tom Lea’s World War II Paintings, Drawings and Eyewitness Accounts. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2008. p. 195.

- Sledge EB. With the Old Breed. New York: Ballantine Books, 1981, xix, 267, 53, 74, 100-101, 134, 156, 100, 235.

- Brandon L. “Making the Invisible Visible: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Military Art in the 20th and 21st Centuries.” Canadian Military History 2009; 3:41-46.

- English AD. “Leadership and Operational Stress in the Canadian Forces.” Canadian Military Journal 2000; Autumn: 33-38.

- Camp, D. Last Man Standing: The 1st Marine Regiment on Peleliu. Minneapolis: Zenith Press, 2009, 169-171, 39, 130, x.

- Manchester W. Goodbye Darkness: A Memoir of the Pacific War. Boston: Little Brown & Company, 1980, 308-309,309, 310, 310-311.

- Against the Odds, season 2, episode 2, “The Death Ridges of Peleliu.” Directed by Sammy Jackson, written by Joseph Alexander, Sammy Jackson, and Norman Stahl. Aired February 22, 2016 on American Heroes Channel.

- Miller DL. D-Days in the Pacific. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. p. 169, 171, 180-182.

- Baird PD. “A Young Doctor Goes to War.” Experience, Winter 2008; 35-36.

- Steinberg R. Island Fighting, World War II. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1978, 182, 184-185, 189.

GREGORY W. RUTECKI received his medical degree from the University of Illinois, Chicago in 1974. He completed Internal Medicine training at the Ohio State University Medical Center (1978) and his fellowship in Nephrology at the University of Minnesota (1980). After twelve years of private practice in general nephrology, he entered a teaching career at the Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, and the University of South Alabama in Mobile, Alabama. While at Northwestern, he was the E. Stephen Kurtides Chair of Medical Education. He now practices general internal medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 9, Issue 4 – Fall 2017