Shameemah Abrahams

Cape Town

|

|

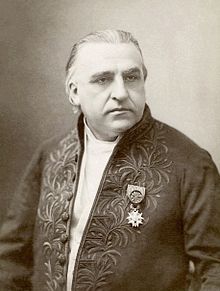

A portrait of the pioneering |

The human mind, so capable of creating works of genius like the orchestral sounds of Beethoven’s symphonies, da Vinci’s enigmatic artwork, or the majestic pyramids of Giza, can easily lose itself and spiral into the chaotic tragedy of dementia. Various forms of “frailties” of the mind have been seen in the artistically astute, as with the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche,1 the painter Thomas Eakins, or even the boisterous American president Theodore Roosevelt.2,3

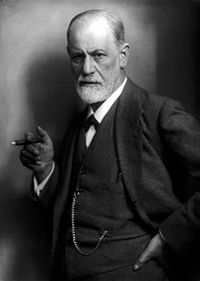

One of the most prolific forerunners for neurology was 19th century neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, well-known and applauded for his keen perception in diagnosing neurological disorders. Controversially, he used his diagnostic insight to characterise the symptoms and cause of hysteria, hypnotising patients before a public audience, and deducing that the root of the symptoms of hysteria was anatomical damage to the brain—a physical as opposed to a non-physical disruption.4 There was strong opposition to his theory and in the early 1900s German physicians categorised nervous system maladies into neurological diseases (physical conflict) and neurosis (emotional conflict5,6)—from which sprouted Sigmund Freud’s popular pioneering “talk therapy” or psychoanalysis.7,8 It is interesting to ponder the effect of brain damage, whether at the physical or emotional level, in altering personalities. As in Charcot’s example, hysteria would often result in uncontrollable and often uncharacteristic outbursts from patients.9

Can hallucinations and other dissociative disorders possibly be a coping mechanism, as Shakespeare so aptly sketched the guilt-riddled Macbeth as he envisioned the murderous floating dagger moments before the heinous deed?10 When a crisis or traumatic event occurs humans respond differently, and it is highly probable that some produce a fictitious reality within the actual reality of our world and eventually the two can become one. Some are of the opinion that mental disorders, especially the psychological (neurosis), could be a result of our ancestral link to the “spirit” world, or a previous intimate connection to the divine, in the form of prophetic visions.11 Hence, the theory suggests that some of us can still hear voices in our head or experience vivid hallucinations (or dreams) which seem concrete and united with the real world. So do we infer that mental patients are a select group of superfluous prophets? Do we look back to the eerie lunatic asylums, as they were once called – into the dark and messy past of psychiatry (formerly alienism) to find answers?

|

|

A portrait of physician Sigmund |

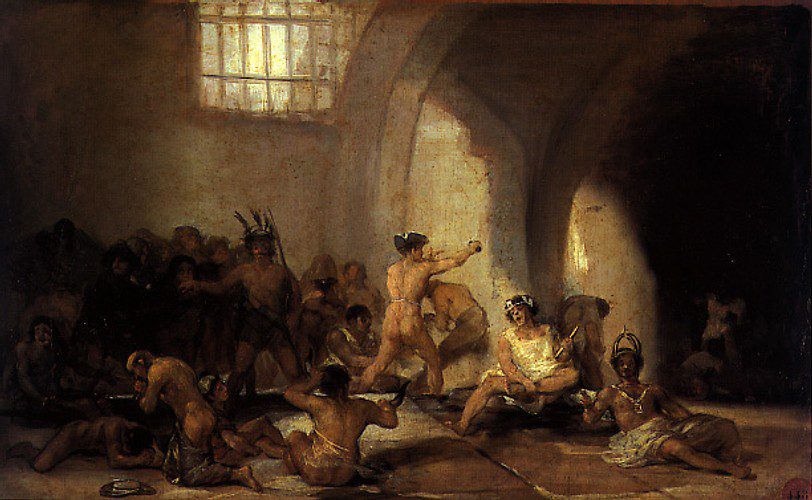

The harsh rays of sunlight fall upon a striking scene of contorted bodies, exposed and lurid. Francisco Goya depicted a mental asylum in his painting titled Casa de locos or The Madhouse with a keen detail and accuracy of the physical and mental struggles in asylums circa 1800. The painting displays half or fully-naked people in nonsensical positions, grovelling on a hard stone floor or enacting a fictitious combat scene. Goya also captured a variety of personas – some identifiers are crowns on the brow with adornments around the neck displaying aristocracy, or the presence of a hat distinctive to sailors, thus aptly juxtaposing fragments of a normal society and an amalgamation of the bizarre and chaotic society of asylums. This defiled status of mental patients has often been linked to those infamously dark and early years of psychiatry.12 The abhorrent treatment of those with mental disorders was due to a lack of understanding and a fear of those who seemed at the edge of humanity—beyond which lay an incongruous and insurmountable abyss. This daunting chasm of knowledge can also be seen in the disarray of Goya’s madhouse. Not only did he portray the mental disturbances of the insane through their absurd actions and the blurry portrayal of their bodies, but the shadows in the dark corners and the skulking figures possibly indicate the shadowy existence of those who were slowly losing their humanity.

These patients’ early tortured treatment is sadly akin to their own tumult of confusion of the reality that they viewed as real and the one everyone else tried to convince them was real. This tortured existence in some small way can be inferred from their constant denial of the actual reality (especially when forcibly confronted as seen in many case reports13), and the normal person’s obstinate view and treatment of them, as can be seen in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s harrowing description of life as a mental patient.12 Although Goya’s painting depicts a specific time period almost 200 years ago, it captured the essence of the tormented mind and existence of mental patients up to this day.

|

|

Casa de locos, 1812–1819 |

In the past, the schism in neurology was that some attributed mental disorders to traumatic changes in the psyche of individuals (mind), while others, like Charcot, targeted tissue damage in the brain (physical). For the past decade, however, brain activity or abnormal flow of brain chemicals (neurotransmitters) has been the target for mental disorders ranging from schizophrenia to addiction disorders, since the development of the neurological tests, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electro-encephalopathy (EEG).14,15 Are the minute electrochemical signals (also known as action potentials) the only sign of an intricate network of connectivity between the physical matter and the intangible mind? Where does the one begin and the other end?

The aberrations observed in behavior, speech, and personality of those who suffer from brain damage, as glimpsed at in Casa de locos, have been studied from the time of lunatic asylums to the current day.13 Although many brain regions have been associated with certain disorders,16 are we any closer to discovering the true causes of these debilitating disorders? Can we assume, as Charcot did, that nervous tissue damage alone causes mental disorders, even though some cases of mental dysfunction have normal brain morphology?15 Do we pursue the current thought that the answer lies in the elaborate and minute web of electrical and neurochemical signalling, as some fMRI and EEG studies have shown?17 In addition, the infant field of affective neuroscience, coined and described by Panksepp,18 uses modern technology (such as EEG) to measure the intangible human mind and emotions. Could this be the answer to resolving the mind versus physical schism in neurology?

On a metaphysical level, are dissociative diseases (such as hysteria) a sign of degeneration in human society? Or is there an evolutionary benefit to our sixth sense? Are the voices and visions which are disassociated from the material world, portents from “beyond”, like the ghost of Hamlet’s father proclaiming: “The serpent that did sting thy father’s life/Now wears his crown”?19

References

- Orth M, Trimble MR. Friedrich Nietzsche’s mental illness–general paralysis of the insane vs. frontotemporal dementia. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;114(6):439–44; discussion 445. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00827.x.

- Leibold C, Eakins T. Thomas Eakins in the Badlands. Archives of American Art Journal. 1988;28(2):pp. 2–15. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1557509.

- Stiles A. Time Capsule: Go rest, young man. Monitor on Psychology. 2012:32. Available at: http://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/01/go-rest.aspx. Accessed February 27, 2013.

- Kumar DR, Aslinia F, Yale SH, Mazza JJ. Jean-Martin Charcot: the father of neurology. Clinical medicine & research. 2011;9(1):46–9. doi:10.3121/cmr.2009.883.

- Oppenheim H. Wie sind diejenigen Fälle von Neurasthenie aufzufassen, welche sich nach Erschütterung des Rückenmarks insbesondere nach Eisenbahnunfällen entwickeln. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1888;14:194–196.

- Holdorff B, Dening T. The fight for “traumatic neurosis”, 1889–1916: Hermann Oppenheim and his opponents in Berlin. History of Psychiatry. 2011;22(4):465–476. doi:10.1177/0957154X10390495.

- Freud S. Lines of advance in psycho-analytic therapy. In: In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works.; 1955:157–168.

- Brunner J. Will, Desire and Experience: Etiology and Ideology in the German and Austrian Medical Discourse on War Neuroses, 1914–1922. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2000;37(3):295–320. doi:10.1177/136346150003700302.

- Gilman S. The Image of the Hysteric. In: Gilman S, ed. Hysteria Beyond Freud,. Berkeley; Los Angeles; London:: University of California Press; 1993:345–452.

- Shakespeare W. Macbeth. 2010 ed. (Kennedy RB, ed.). Collins Classics; London: Harper Press; 1606:67–9.

- Cangas A, Sass L, Pérez-Álvarez M. From the visions of Saint Teresa of Jesus to the voices of schizophrenia. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology. 2008;15(3):239–250.

- Perkins Gilman C. The yellow wallpaper. The Yellow Wall-Paper and; 1973.

- Sacks O. The man who mistook his wife for a hat: And other clinical tales. Simon & Schuster; 1998.

- Mandal DK, Bandyopadhyay S, Tarafdar J, et al. Eating epilepsy: a study of twenty cases. Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 1992;90(1):9–11. Available at: http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/1593147.

- García-Campayo J, Fayed N, Serrano-Blanco A, Roca M. Brain dysfunction behind functional symptoms: neuroimaging and somatoform, conversive, and dissociative disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2009;22(2):120–127. Available at: doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283252d43.

- SM S, Bird T, Nochlin D, Raskind M. Familial presenile dementia with psychosis associated with cortical neurofibrillary tangles and neurodegeneration of the amygdala. Neurology. 1992;42:120–127.

- Gautier JF, Chen K, Salbe a D, et al. Differential brain responses to satiation in obese and lean men. Diabetes. 2000;49(5):838–46. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10905495.

- Panksepp J. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004:480.

- Shakespeare W. Hamlet. 3rd series. (Thompson A, Taylor N, eds.). The Arden Shakespeare; 1603.

SHAMEEEMAH ABRAHAMS majored in biochemistry and physiology for her BSc (2008–2010) with honors in physiology, specializing in neuroscience (2011) at the University of Cape Town (UCT). She is currently in her second year as a MSc (Med) student at the UCT/MRC Exercise Science and Sports Medicine (ESSM) unit, Department of Human Biology, UCT, under the supervision of Dr. Michael Posthumus and Dr. Alison September. Her project deals with both non-genetic and genetic predisposing factors of concussion risk in South African schoolboy rugby. Her research interests include brain injury, physiological changes during exercise and genetic predisposition to injury.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2014 – Volume 6, Issue 1

Winter 2014 | Sections | Neurology

Leave a Reply