Anika Khan

Karachi, Pakistan

“…what will you carry back from this field trip into my endless solitude?”

From The Diving Bell and the Butterfly by Jean-Dominique Bauby (1997)

|

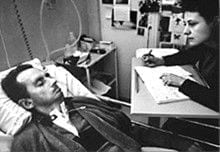

| Jean-Dominique Bauby “dictating” the passages of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly that he had earlier revised in his head. Photograph by Jeanloup Sieff. |

In December 1995, Jean-Dominique Bauby suffered a massive stroke that made him a prisoner in his own body.1 Within the space of a few hours, his hectic, animated existence as the gregarious editor of the French fashion magazine Elle crumbled into nothingness. Bauby went into a coma and emerged from it twenty days later, unable to move, speak, or swallow. He had begun what Sontag called an “onerous citizenship” in a dark and difficult kingdom.2 His former life was irretrievably lost to him. He was diagnosed with “locked-in syndrome,” a neurological condition in which the afflicted individual is physically paralyzed but retains mental alertness — a bizarre combination of complete paralysis and lucid inner awareness that seems almost to be a stroke of cosmic irony, a joke played by the gods on hapless mortals.3

After emerging from his coma, Bauby’s only interface with the world was through the ability to blink his left eyelid. Through this tiny window of communication, he learned to express his inner thoughts, blink by arduous blink, to write a brief but incredible memoir. Written in the Naval Hospital at Berck-sur-Mer, the French version of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly was published in 1997, just two days before he died.4 Bauby’s invaluable contribution to literature is his unveiling of the inner world of an individual with locked-in syndrome. It is also the story of great loss and a testament to his endurance and courage.

Penning the memoir became possible when Bauby’s speech therapist (his “guardian angel”) placed the alphabet in his room, the letters arranged according to the frequency of their use in the French language. Through this arrangement of letters, a laborious system for communicating with visitors evolved. The grueling journey of writing the book involved his publisher’s assistant reading out the letters of the arranged alphabet until Bauby blinked at the right one. Blink by blink, the letters were strung into words and words into sentences and paragraphs that Bauby had written, revised and rehearsed earlier in his head.

The title of Bauby’s book uses the metaphor of a “diving bell” to describe his locked-in state: trapped in an iron cage, he had left behind the boundaries of the familiar world and inexorably descended to the unfathomable depths of an uncharted sea. Reading his memoir is like listening to a lost voice: it rises unexpectedly from the deep and startles us with its richness, its wit, and its gift for keen observation. But there is more to Bauby’s book than the surprise occasioned by meeting the unclouded intelligence imprisoned within his silent, immovable body. Written in beautiful, evocative prose, his memoir takes us inside his “invisible and eternally imprisoning cocoon,” and reveals to us his rich imagination, the “butterfly” that allowed him to escape from his oppressive confinement and “wander off in space or in time, set out for Tierra del Fuego,” or visit the woman he loved to “stroke her still-sleeping face.” Remarkably, Bauby’s account is rarely sentimental. Writing with irony and self-deprecating humor, in a voice that is sardonic and poignant by turns, he weaves into his book memories from his past existence, encounters with medical professionals, and experiences of life as a permanent hospital inmate.

Occasionally, he allows us to witness his grief over the loss of a thousand everyday pleasures of which he can never partake again: the taste of sausage, witty conversation, the ability to embrace a child. Describing an outing on Father’s Day with his two children, he writes, “His face not two feet from mine, my son Theophile sits patiently waiting – and I, his father, have lost the simple right to ruffle his bristly hair, clasp his downy neck, hug his small lithe warm body tight against me.” In another poignant episode, he describes a brief trip to Paris for medical advice. As the ambulance carrying him drove past the cafe where he used to drop in from work for “a bite,” he shed a few tears. With characteristic irony, he writes, “I can weep discreetly. People think my eye is watering.”

A major theme of the book is Bauby’s experience of sickness and his contact with the physicians and staff that cared for him. The short chapter “The Wheelchair” illuminates the difficulty of understanding a patient’s experience of sickness and the different vantage points from which healthcare professionals and those who are sick view events. Waking up from his coma at the Naval Hospital at Berck-sur-Mer, he was initially dazed and unsure of his prognosis, believing that he would soon recover. He relates that as his mind became clearer, he was already making plans for new projects to undertake when he left the hospital. After having been at the hospital for a few weeks, there was a day on which Bauby was dressed (“Good for the morale,” pronounced the neurologist”) and placed in a wheelchair. As two attendants “dumped” him “unceremoniously in the wheelchair,” Bauby realized the horrifying truth: there was no hope for his recovery. This moment of devastating realization, which he describes as “keener than a guillotine blade,” signified a sort of success from the viewpoint of the healthcare team. “You can handle the wheelchair,” the occupational therapist told him in celebratory tones.

His voice takes on a more scathing tone when relating a different encounter with a medical professional: He woke suddenly one morning to find the hospital ophthalmologist leaning over him and with calm indifference, sewing his right eyelid shut, “just as if he were darning a sock.” Bauby writes, “I have known gentler awakenings,” and describes the fear that swept over him as he wondered if this man would sew up his left eye as well – “the one tiny opening” of his cocoon. “Six months!” barked the ophthalmologist, offering no further explanation for the procedure. Bauby describes his desperate attempts to question the man by signaling with his working eye, but to no avail. He remarks with an irony that has tragic overtones, “this man – who spent his days looking into other people’s pupils – was apparently unable to interpret a simple look.”

The distance between the perspectives of the patient and the physician is an inevitable part of the human condition: we can only look at the world through our own eyes and must strive to understand a different viewpoint.5 Bauby’s memoir underscores the importance for physicians and caregivers of taking a deeper, more empathetic look at the incapacity and helplessness experienced not only by patients with locked-in syndrome, but by analogy, other patients who have no way of giving voice to their experience of sickness.6 Often, patients become diseases, numbers and syndromes to healthcare professionals who have repeatedly seen illness and have lost the capacity to relate to the experiences of patients. Bauby’s experience on the wheelchair illustrates this chasm by contrasting his inner devastation with the medical team’s casual understanding of the moment. His world was shattering while the attention of the “many white coats” surrounding him centered on the minutiae of his wheelchair drive. We all struggle to understand the pain of others, but Bauby reminds us, lightly and courageously, that it is important to keep struggling to connect on a human level with patients and be more perceptive of their experience of sickness.

Illness strips people of control over their lives. It takes away things that they deem essential to their identity, that make them who they are. In Bauby’s case, his illness robbed him of his identity as a popular editor of a prestigious fashion magazine, moving in elite circles. To most eyes, he had become a shell, an empty husk, a ‘vegetable’. But the restless, vibrant voice inside his motionless and wasted frame makes us reexamine our notions of humanity and personhood. Bauby gives us access to a world that we could otherwise not have explored, taking us with him in his diving bell to the depths of the sea and showing us how he escaped the unmitigated darkness of his prison through his imagination that soared, butterfly-like. For medical professionals, his book is a reminder, an invitation to look at the world through the eyes of the sick, “those castaways on the shores of loneliness.”

References

- Kar Yee Katherine Law, “Exploring ‘Locked-In Syndrome’ Through the Case of Jean-Dominique Bauby,” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse 3, no 03 (2011), http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=418

- Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor, (New York: Random House Vintage Books, 1979), 3

- Eimear Smith and Mark Delargy, “Locked-in syndrome,” BMJ: British Medical Journal 330, no. 7488 (2005): 406.

- Thomas Mallon, “In the Blink of an Eye,” New York Times, June 15, 1997, http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/06/15/reviews/970615.mallon.html

- S. Kay Toombs, The Meaning of Illness: A Phenomenological Approach to the Different Perspectives of Physician and Patient, (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1991), 10

- John L. Coulehan, Frederic W. Platt, Barry Egener, Richard Frankel, Chen-Tan Lin, Beth Lown, and William H. Salazar, ““Let me see if I have this right…”: words that help build empathy,” Annals of Internal Medicine 135, no. 3 (2001): 221-227

All quotes from The Diving Bell and the Butterfly have been taken from Jeremy Leggatt’s English translation (published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate Limited in 1997).

A First Vintage Edition of Leggatt’s translation, published in 1998 as The Diving Bell and the Butterfly: A Memoir of Life in Death is currently available on Amazon at https://www.amazon.com/Diving-Bell-Butterfly-Memoir-Death/dp/0375701214)

ANIKA KHAN works as faculty at the Centre of Biomedical Ethics and Culture, SIUT, Karachi, Pakistan. She has a Master in Bioethics and is involved in the Centre’s research and educational activities. In the Centre’s academic programmes, she teaches medical humanities and takes sessions related to gender and ethics.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Summer 2017 – Volume 9, Issue 3

Spring 2017 | Sections | Neurology