Lee W. Eschenroeder

Charlottesville, Virginia

|

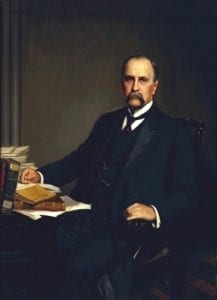

| Sir William Osler |

On May 1, 1889, Sir William Osler, one of the greatest clinicians and educators of all time, stood before students at the University of Pennsylvania and delivered the valedictory address “Aequanimitas.” Since that day equanimity, or “imperturbability” as Osler also named it, has become one of the most prized qualities of a physician. Wherever the legend of Osler has traveled, and everywhere in American medical education, praise for equanimity has followed. At Johns Hopkins University, one of the nation’s premier medical centers and Osler’s former home, new residents are welcomed into their “Osler residency” with a copy of the original address and a necktie or scarf patterned with white shields bearing “aequanimitas.” One would guess that these residents, soon to be among the best-trained physicians in the country, wonder little which quality they ought to cultivate.

But what is equanimity? It is not a word common in our daily conversation and amidst our idolatry of the man and unexamined use of the term we may have lost sight of what Osler meant. According to Sir William, “imperturbability means coolness and presence of mind under all circumstances, calmness amid storm, clearness of judgment in moments of grave peril, immobility, impassiveness, or, to use an old and expressive word, phlegm.” It is “largely a bodily endowment,” which demands “medullary centers under the highest control” capable of preventing “the slightest dilator or contractor influence [to] pass to the vessels of [one’s] face under any professional trial.” Contrary to modern day feel-good commencement speeches promising a dream fulfilled for each graduate, Osler counseled his audience that some of them would never attain equanimity “owing to congenital defects” and that for others there was “disappointment, perhaps failure” in store in their careers. However, those who possessed the physical capacity and who devoted themselves to “an intimate knowledge of the varied aspects of disease” could hope to acquire this “divine gift, a blessing to the possessor, a comfort to all who come in contact with him.” For the equanimous physician, “the possibilities are always manifest, and the course of action clear.” Much of this is consistent with the image of the master clinician we think of today: the person able to navigate the chaos of the trauma bay, the mystery of the un-diagnosable illness, or the grief of the deathbed with equal acumen; a person who is not at the mercy of wild emotions and yet feels no less than the rest; one whose judgment and knowledge rise above all others to rescue life when it can be saved and to bring peace when it cannot.

In the modern era, however, when physicians are criticized for their insensitivity and robotic objectivity, it is equally important to revisit Osler’s words for a description of what equanimity is not. “From its very nature, [equanimity] is liable to be misinterpreted, and the general accusation of hardness, so often brought against the profession, has here its foundation.” Osler was aware of the potential harms of imperturbability and warned his audience to seek that virtue to the extent that it would allow them “to meet the exigencies of practice with firmness and courage, without at the same time hardening ‘the human heart by which we live.’” Rather than call for the sacrifice of community and spirituality on the altar of scientific study, he described “a clear knowledge of our relation to our fellow-creatures and to the work of life” as “indispensable.” The son of a reverend and an ardent student of the classics, Osler was well informed by his attempts to understand the plight of man before he sought to understand his physiology.

And yet, Osler’s examples emphasize tolerance of the foibles of others rather than giving answers to the true challenges to equanimity a physician faces. It is easy enough to suggest that doctors “deal gently . . . with this deliciously credulous old human nature in which we work” and forgive patients for their embrace of “a case of Warner’s Safe Cure” or other forms of quackery. But what should become of our equanimity when a twenty-five-year-old medical student who will not survive the car accident from a trip to see her fiancée is in our care? Should we remain imperturbable when cancer claims the life of another young woman, a daughter and sister, who has fought her illness for four years? On the role of equanimity in these weightier topics, that day in 1889 offered no answers.

But then Osler was speaking on a celebratory occasion and was likely playing to his audience. Stories about misbehaving patients get more laughs than tragedies. It is also unlikely that he had any sense of the degree to which his words on that day would influence the profession of medicine for more than a century thereafter. Yet questions like these do bear answering, if only because all practicing physicians have encountered tragedies like the aforementioned examples and wondered what they should do. Is it better to strip one’s humanity bare and weep alongside a patient’s family or attempt to offer strength and stability with just a comforting hand and a willingness to listen? Does the medicalization of tragedy through explanations of hemorrhagic shock or immunosuppression offer anything of value, or should physicians just sit with their patients in awe of the mystery of death and the tragedy of loss?

Perhaps Osler did not address such issues because of the tone of the occasion, or perhaps he omitted them because he had no answers to give. What advice he does give in this regard is indirect at best. The chief threats to equanimity, he notes, are the “very hopes and fears which make us men. In seeking absolute truth we aim at the unattainable, and must be content with finding broken portions.” The imperturbable physician gives confidence to patients because he knows the disease with which he contends and knows how to handle it with certainty. Death and other forms of tragedy are among those unknowable and absolute truths of which we are only offered fragments, often with sharp edges that cut and scar. It is a paradox: the “very hopes and fears” that make us human, capable of sharing in the pain of loss, are the chief challenges to our equanimity. Stated differently, our humanity threatens our equanimity. And at the threshold of absolute truth, our ignorance is revealed and we are left searching for splinters in the sand.

Undoubtedly, those who have observed equanimity exemplified in their colleagues have also seen its most dangerous mimic—apathy. Apathy is physical imperturbability born not of control and discipline but of an absence of feeling. Apathy is fast, efficient, and easily forgives patients because it never trusted them in the first place. Apathy does not suffer mystery because it does not seek truth. Most frighteningly, apathy, in many settings, is quite functional and offers freedom from emotional obstacles that obstruct ambition and public recognition. Even those who enter their careers full of feeling and good intention are susceptible to its growth, as emotions denied in the moment are never revisited and fully processed until they cease to occur altogether. And, while physicians may vary in their ability to identify this quality in their colleagues and in themselves, patients possess an unbeatably discerning eye for those who fall on either side of the line. In those moments, when we must confront unbelievable tragedy or unbelievable joy at a patient’s side, there is no question in their mind which quality it is that we possess.

Osler, ever the optimist, also offered this: “each one of us may pick up a fragment [of truth], perhaps two, and in moments when mortality weighs less heavily upon the spirit, we can, as in a vision, see the form divine.” As physicians, we spend our lives collecting fragments, and we will be cut by many of them and feel small in the shadow of the absolute truth they represent. It is apathy that puts on gloves and tosses them in the sack—no cuts, more productivity. If we are to achieve Aequanimitas, however, we must continue to handle these shards of truth with our bare hands and to allow the scars they give us, for it is only in touching them, in feeling their contours down to the most minute detail, that we can catch a glimpse of the divine to sustain us.

References

- Osler, William. “Aequanimitas”. Celebrating the Contributions of William Osler. N.p., 1999. 27 Nov. 2016. http://www.medicalarchives.jhmi.edu/osler/aequessay.htm

LEE ESCHENROEDER is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Virginia (UVa) School of Medicine and incoming internal medicine resident at the University of Washington. A member of the AOA and Gold Humanism Honor Societies, he is also a former corps member for Teach for America. He is interested in education, public health, and working with underserved populations in the United States.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 9, Issue 4 – Fall 2017

Leave a Reply