Denis Chen

Newcastle-under-Lyme, United Kingdom

Beauchamp and Childress published Principles of Biomedical Ethics in 1979, introducing the “Four Principles” of medical ethics: beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice.1 They argued that “best” treatment depends on patient preferences and applied to all cultures and societies. These principles were philosophically underpinned by the duty-based ethics of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) and affirmed by the Supreme Court of the United States, but may not be as universal as proposed.2 Chinese society, founded on Confucianism, results in more beneficence-orientated and less autonomy-focused medicine, and in one US study, Spanish-speaking patients preferred a paternalistic physician relationship.3,4

Historically, patients have never had autonomy over all options. Various factors narrow options down to what is realistic, affordable, and feasible. Autonomy to choose between two good options of relative benefit is accepted, yet autonomy to choose an objectively suboptimal choice is complicated. When there are two choices of unequal absolute benefits, medical schools and established guidelines ensure that graduating doctors recommend what is optimal, hence somewhat constraining patient autonomy.

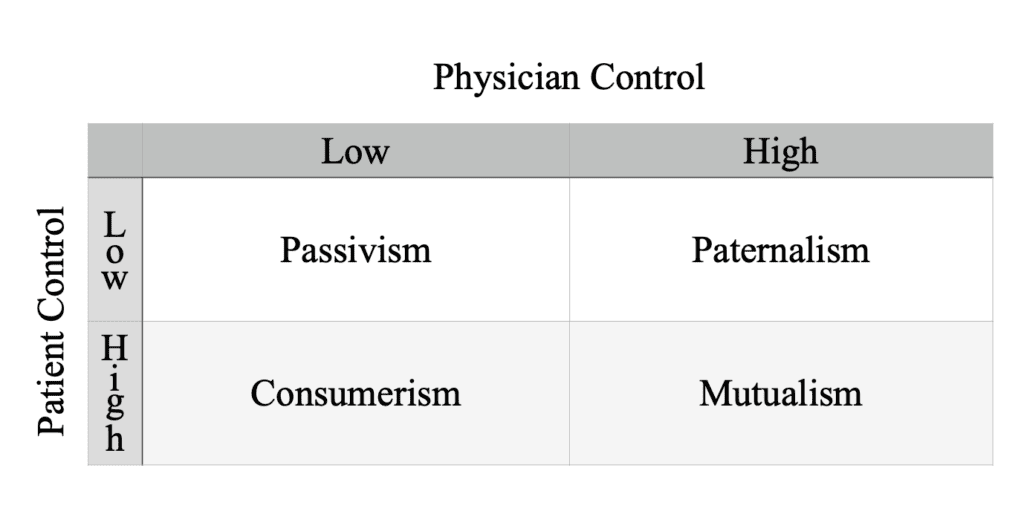

Patient partnerships have been categorized by the extent of physician and patient control.5 Soft paternalism is beneficence-focused, emphasizing treatment efficacy rather than patient preference, while hard paternalism is authoritarian. The opposite, hard autonomy, regardless of beneficence, is consumerism. A doctor without a focus on beneficence precipitates consumerism and passivism and is arguably not upholding the morality of their professional role.6,7

When facing a challenging clinical choice, a patient may respond, “You’re the doctor.” A patient’s decisions are made based on their understanding of the concept of treatments as presented by the doctor. If these are poorly communicated, and a patient undergoes treatment significantly different from their expectations, the patient did not have autonomy over their received treatment.

Patient autonomy leads to better satisfaction but its effects on patient outcome is mixed.8-10 In a Taiwanese study, high perceived autonomy improved physical and mental quality of life, but only for patients with high decisional preference.11 A French study affirmed the existence of patients with low decisional preference, with 21% of breast cancer patients preferring to defer decisions to doctors.12 Hence, the focus must be on a patient-centered approach and not forced autonomy.

Health inequality needs to be approached with care. Studies show that efforts to improve patient autonomy that is dependent on health literacy can worsen inequality.13,14 Providing different choices increases costs and complicates logistics, so autonomy could be viewed as inefficient from a utilitarian lens. Yet, hospitals would hugely benefit from patient-centered care with shorter lengths of stay, lower cost per case, decreased adverse events, greater employee retention, and fewer malpractice claims.15 Evidence suggests the goal should be a patient-centered approach, where there is a choice to carry the burden of responsibility that comes with autonomy; in a sense, the choice to choose or reject autonomy.

References

Full reference list available upon request.

- Beauchamp, T.L. and Childress, J.F. (2019). Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 8th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ubel, P.A., Scherr, K.A. and Fagerlin, A. (2018). Autonomy: What’s Shared Decision Making Have to Do With It? The American Journal of Bioethics, 18(2), pp.11–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2017.1409844.

- Varkey, B. (2020). Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their Application to Practice. Medical Principles and Practice, 30(1), pp.17–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000509119.

- Tsai, D.F. (1999). Ancient Chinese medical ethics and the four principles of biomedical ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics, 25(4), pp.315–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.25.4.315.

- Panahi, S., Spearman, B., Sundrud, J., Lunceford, M. and Kamimura, A. (2023). The Impact of Patient Autonomy Among Uninsured Free Clinic Patients. The Impact of Patient Autonomy Among Uninsured Free Clinic Patients, 10, p.237437352311790-237437352311790. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735231179041.

- Roter, D., & McNeilis, K. S. (2003). The nature of the therapeutic relationship and the assessment of its discourse in routine medical visits. In T. L. Thompson, A. M. Dorsey, K. I. Miller, & R. Parrott (Eds.), Handbook of health communication (pp. 121–140). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Lewis, J. and Holm, S. (2022). Patient autonomy, clinical decision making, and the Phenomenological reduction. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 25(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-022-10102-2.

- Rothman, D.J. (2001). The Origins and Consequences of Patient Autonomy: A 25-Year Retrospective. Health Care Analysis, 9(3), pp.255–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1012937429109.

- Birkeland, S., Bismark, M., Barry, M.J. and Möller, S. (2021). Is greater patient involvement associated with higher satisfaction? Experimental evidence from a vignette survey. BMJ Quality & Safety, 31(2), pp.86–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012786.

- Mead, N. and Bower, P. (2002). Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: a review of the literature. Patient Education and Counseling, 48(1), pp.51–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00099-x.

- Lee, Y.-Y. and Lin, J.L. (2010). Do patient autonomy preferences matter? Linking patient-centered care to patient–physician relationships and health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine, 71(10), pp.1811–1818. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.008.

- Milliat-Guittard, L., Charlois, A.-L., Letrilliart, L., Favrel, V., Galand-Desme, S., Schott, A.-M., Berthoux, N., Chapet, O., Mere, P. and Colin, C. (2007). Shared medical information: Expectations of breast cancer patients. Gynecologic Oncology, 107(3), pp.474–481. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.001.

- D’Costa, S.N., Kuhn, I.L. and Fritz, Z. (2020). A systematic review of patient access to medical records in the acute setting: practicalities, perspectives and ethical consequences. BMC Medical Ethics, 21(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-0459-6.

- Kim, H. and Lee, A. (2023). How patient autonomy drives the legal liabilities of medical practitioners and the practical ways to mitigate and resolve them. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 99(1168). doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/postmj/qgad003.

- Yau, C.W.H., Leigh, B., Liberati, E., Punch, D., Dixon-Woods, M. and Draycott, T. (2020). Clinical Negligence costs: Taking Action to Safeguard NHS Sustainability. BMJ, 368(368), p.m552. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m552.

DENIS (TING-HSIAN) CHEN is a Taiwanese medical student at Keele University, United Kingdom. He began playing the violin at the age of three and has always been fascinated by the medical humanities.

Leave a Reply