Steve Wheeler

Greenwich, London, England

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

The human fascination with fear of the unknown has been documented in art and literature across civilization for centuries. In every culture, this has manifested itself in the form of creatures as bizarre as they are terrifying. Since the evolution of language, humans have invented and told stories about monsters to rationalize that which we cannot see, predict, or explain. In this way we pin these phenomena down in solid form, making the incomprehensible comprehensible. The human experiences of fear and anxiety are thus rendered visible in pencil, pen, and paint, leaving tangible evidence of their existence in the form of monster art.

Monster art takes myriad forms inspired by the world around us or by aspects of our own humanity. Perhaps the most awe-inspiring are those monsters associated with the ocean, such as the Kraken or Leviathan, to name some famous examples. The world’s oceans are mysterious, dangerous, unpredictable, and ever-changing. It is not surprising, therefore, that ocean monsters feature heavily in human narrative as symbolic representations of the more unsettling aspects of our existence.

As both a scholar and practicing artist, I have observed that monster art frequently becomes a vehicle of expression for the human mind, especially in times of duress. Art in general is sensitive to the prevailing mood of the society that produces it, so it is my theory that periods of great upheaval should precipitate a proliferation of monsters in the art of the peoples experiencing it. This is seen in the monster art of late eighteenth century Britain and mid nineteenth century Japan.

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, the combination of industrialization and the Napoleonic wars had a profound impact on British society, disrupting social structures, traditions, and entire ways of life across the country. Nearly a century later, Japan was facing famine, economic stagnation, and an evermore unstable ruling class. In 1854 the arrival of Commodore Perry’s fleet of gunships in Edo (modern Tokyo) heralded Japan finally opening fully to Western trade, which would completely transform the country.2

Despite occurring on opposite sides of the world and nearly a century apart, these troubled periods are both marked by a fascination for the extreme and the weird. For all the differences between Japan and Britain in terms of history and culture, there are striking similarities in how the sea monsters of their respective mythologies manifest in response to the trauma and anxiety brought about by social upheaval. In both cases, a combination of social-cultural transformation and political instability led to an atmosphere of fear and anxiety among individuals and society as a whole. The response of many was to turn their gaze inward, focusing on their society’s origins and the mythologies surrounding them in order to rationalize this anxiety.3 These elements together produced a proliferation of sea monsters in the art of both countries.

To illustrate these parallel monster obsessions, I have selected two examples from the variety of art featuring sea monsters; one by romantic era writer and artist William Blake (1757-1827), and the other by ukiyo-e (woodblock print) artist and painter Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1891). Both artists lived and worked in similar environments—the metropolitan centers of Edo and London—which played host to thriving semi-commercial culture. This meant they became centers of art, culture, and entertainment and home to large communities of artisans, writers, and performers. These communities were part of a dense urban network that actively participated in the social and political aspects of urban life. They were ideally placed to pick up the prevailing moods of their surrounding environment.4

Image obtained from Wikipedia Creative Commons

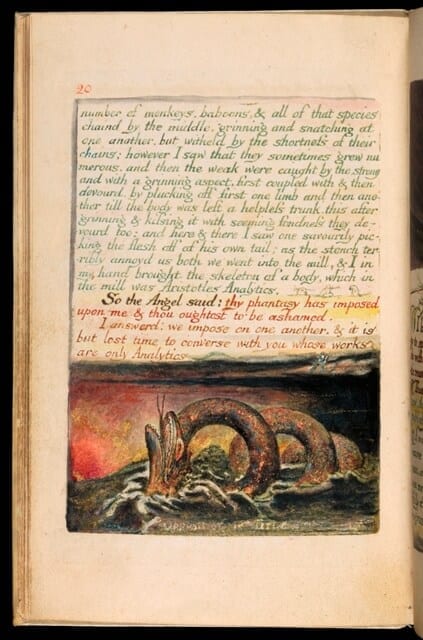

William Blake was part of a small group of like-minded artists and writers who would later be recognized as key contributors to British Romanticism.5 This print (Fig 1) depicts an image of the Leviathan from one of Blake’s early publications, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. As well as biblical scriptures, Blake drew inspiration from many classical Greek and Roman texts and frequently depicted characters and motifs from these works, combining them with his own vivid imagination to produce dramatic scenes of an often violent and apocalyptic nature.6 This is clearly seen in this image, with the huge serpentine body of the Leviathan emerging from the storm-tossed sea. The colors used are intense, from the red and yellow of the sky to the deep green of the monster’s coils. The dramatic contrast of light and shadow together with the monster’s unnaturally large bulk and gaping mouth gives the whole scene a disturbing, unsettling feeling. It conveys a sense of terror and dread in the face of some huge, unstoppable force. Considering that Blake wrote The Marriage of Heaven and Hell during the French Revolution and not long after the Gordon Riots occurred in London, it is not hard to see a reflection of the instability and uncertainty permeating society in Blake’s image of the Leviathan.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi was celebrated during his lifetime for his illustrations of heroes and monsters from Japanese folklore. Like Blake, Kuniyoshi surrounded himself with a circle of fellow artists and writers, all of whom left their own impact on the Edo cultural landscape. As part of the urban educated class, Kuniyoshi was well read not only in the popular works of his day, but also in classical Chinese texts, all of which would become inspiration in his works.7 This can be seen his illustration of (Fig 2) the well-known Japanese fable of Tamatori-hime, a pearl diver who recovered a precious jewel from the underwater palace of the Dragon King. Here, Tamatori-hime is fleeing the palace with the jewel in her grasp, closely pursued by one of the Dragon King’s fearsome attendants. This tale was a favorite subject of Kuniyoshi’s, who produced multiple prints illustrating it. Similar to Blake’s Leviathan, it depicts a stormy sea out of which the monster rises, a great serpentine body with a fearsome head. The colors are vivid and the composition is dramatic, with the dragon frozen at the instant before its attack, maximizing the tension of the scene. Again the monster is depicted in such a way as to give the viewer a sensation of being faced with a powerful, unstoppable force. Interestingly, despite coming from separate literary canons, the creatures depicted have many features in common, from the scaly serpentine bodies to their unnaturally huge size. Despite the separation in geography and culture, the human imagination appears to gravitate towards certain forms that represent common human experiences of awe, anxiety, and terror.

This psychological dimension of art analysis has been the subject of scholars in a variety of disciplines. Art anthropologist Evelyn Hatcher noted that across different cultures, individuals who produced art tended towards a certain personality “type.” An artist-type personality is sensitive to problems and contradictions in their culture. They in turn produce work that reflects these problems, as well as the underlying mood in their environment. This work becomes popular as people recognize these works as expressions of their current experience. Hatcher describes this phenomenon:

“Artistic solutions often provide symbolic or metaphorical statements of relationships which present stimulating analogies. A new symbolic solution is achieved by an individual out of his own psychological needs, yet is perceived by others as meaningful in the social situation so that it is accepted as innovation.”8

Blake, Kuniyoshi, and other artists created sea monster art as a part of a conscious or unconscious expression of the unstable and anxious mood of the society they lived in, but the wider popularity of such work among the general public indicates that this kind of art had significance and meaning or fulfilled a psychological role beyond the mind of the artist alone. Both London and Edo society recognized these images as representing some part of the reality they were living in.

Jungian psychoanalysis would explain this by arguing that the image of the Leviathan or dragon forms a symbol in humanity’s collective unconsciousness, a representation of anxiety and fear for an uncertain future.9 Considering the similarities in form and context of British and Japanese sea monster art, it makes for a compelling explanation, although it certainly not the only one.

This fixation with sea monsters does not belong exclusively in the past. Over the last decade, I have also noticed a contemporary trend towards monsters in popular culture. Whether it is the new interpretation of the Leviathan in the latest Final Fantasy video game, or the mysterious fish-man from Guillermo del Toro’s film The Shape of Water, or even the array of merchandise sporting images of the Kraken and other famous mythological sea creatures, it is clear that monsters are once again enjoying a spike in popularity. Reflecting on the current political, social, and economic climate, it cannot escape anyone’s notice that we are once again living in a time of great uncertainty, where anxiety in the general population is running high. Just as in previous centuries, monsters have once again stepped into the cultural spotlight. It seems that beyond the barriers of time and space, there is something in the human mind that seeks an expression of the anxiety we feel in the face of the uncertain and the unknown.

References

- Stuart Curran, ed., The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism, Cambridge Companions to Literature (Cambridge [England] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- Harold Bolitho, ‘The Tempō Crisis’, in The Cambridge History of Japan, vol. 5 (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

- H. W. Janson, Penelope J. E. Davies, and H. W. Janson, Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition, 8th ed (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2011).

- Harootunian, H.D. ‘Late Tokugawa Culture and Thought’. In The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press, 1989.; Schwarz, Leonard. ‘London 1700-1840’. In The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, 2:641–72. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Wright, Thomas. The Life of William Blake. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Burt Franklin, 1969.

- Makdisi, Saree. William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Schaap, R., K. Utagawa, Van Gogh Museum, and Philadelphia Museum of Art. Heroes & Ghosts: Japanese Prints by Kuniyoshi, 1797-1861. Hotei Pub., 1998.

- Hatcher, Evelyn Payne. Art as culture: An introduction to the anthropology of art. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999. p110

- Jung, Carl Gustav. Man and his symbols. Laurel, 1964.

STEVE WHEELER is a masters graduate from Leiden University, where he specialized in cross-cultural comparison studies of Japanese and British monster art. His life-long interest in art of all kinds has led him to live and study in both Japan and the Netherlands, as well as his home country of Britain. Steve is also a practicing artist, currently working freelance in South-East London and continues his investigations into humanity’s monster obsession in his spare time.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 3– Summer 2021

Leave a Reply