Gerda Kovacs

Aalborg, Denmark

|

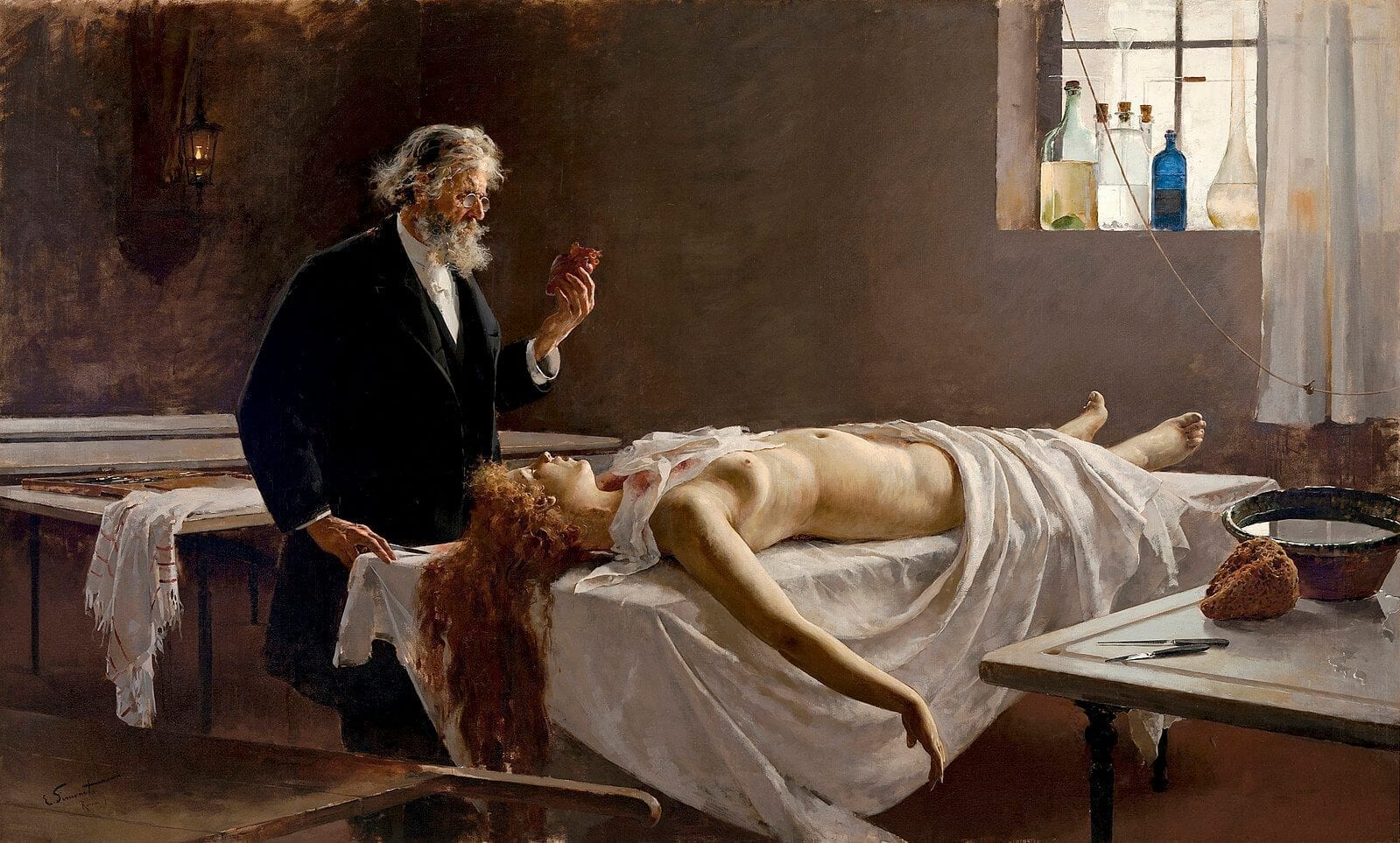

| Enrique Simonet, La autopsia, Oil on canvas. Height: 177 cm (69.7 in.). Width: 291 cm (114.6 in). Museo de Málaga, Málaga, Andalusia, Spain |

“I would like to explode, flow, crumble into dust, and my disintegration would be my masterpiece.”

– Emil Cioran, On the Heights of Despair

Geza Csath, a Hungarian psychiatrist and writer, was born in 1887 and died in 1919. During his short life, he worked at the Moravcsik Psychiatric Hospital in Budapest, produced an overwhelming volume of work in large part fueled by his ever-increasing addiction to opium, killed his wife, then killed himself. He left his mark on the European literary scene as one of the great fin-de-siècle expressionists and one of the country’s first contemporary writers, but he also did something much greater – he revolutionized the relationship between medicine and the humanities.

As a child and teenager, Csath wrote music, drew, and painted passionately. But his music was scorned by his father, a professional musician himself, his paintings and drawings criticized by his drawing teacher, and his application rejected by the Academy of Music. In 1904 he left to study medicine in Budapest, exchanging his love of sound and composition for the intricacies of his fellow man. Only the human body and psyche, it seemed, were large enough to encompass all that he desired to know: everything, about everything.

And everything, it seemed, he encountered. From his diaries, which he kept from childhood to death, we know that in 1910 he was misdiagnosed with tuberculosis, for which opium-based treatment was proposed. It was this human error that brought on his downfall, although arguably also his literary prominence. He took his first dose of Pantopon on 20 April 1910, and the rest is history; or rather the rest is literature, art, legacy, disease, and destruction.

Even though the official story is that he became addicted to opium because of this misdiagnosis, that is a tale told half-heartedly, even by Csath himself. He took opium not because he thought it would do his lungs any good, but because he wanted to see if it would do him any good.1 His feverish curiosity, not particularly tied to either medicine or art but more to the world at large, made him want to push his body and mind as far as they would go, and then follow them, notebook and pen in hand, into whatever vast and dark jungle they ended up in. He was his own most diligent observer and student, pushing himself deeper and deeper into mayhem and addiction, just to keep track of everything and to record it precisely as it happened. Meticulous in his experiments, he chased himself calmly through hell for a few scraps of knowledge.

But Csath was also an artist before he was anything else, and he believed in keeping evidence not only for the sake of knowledge and progress, but also out of despair. He recorded everything; his existence, dreams, suffering, life, worries, the simple pleasures of a conversation with two good friends on a balcony, a few moments spent in the sunlight, his hatred and sins. He turned these everyday events into literature, keeping evidence of the fact that he lived and existed, not only as a medical experiment to be concluded at some point, but also as a human being whose existence would soon be forgotten and irrelevant despite everything he might have done when he was still alive, unless he took it upon himself to make people remember him. He was dedicated to himself, and because his own self was such a glorious mixture of medicine and art, science and the humanities, he was also dedicated to all of these subjects simultaneously, granting him permission to the field of wonder that exists between these disciplines, usually so isolated from each other.

In The Ethics of Addiction, fellow Hungarian psychiatrist Thomas Szasz proclaims that heroin addiction should not be interfered with by external powers, since “we must regard freedom of self-medication as a fundamental right.”2 This libertarian perspective on addiction and its treatment is also reflected in Csath’s attitude. Indeed, his use of language when describing his addiction is free of the moral undertones and embellishments that often follow such topics, yet not devoid of the literary flow, not as medically sterile as his observatory role could prompt him to be. In the summer of 1912 he wrote in his diary, “[My cousin and I] arrived at Stubnya on a windy, chilly spring midday. The large restaurant presented an unfriendly picture. We were cold, strangers. I worried about every move I made, and tried to find a way of winning everyone over as easily and stylishly as possible. I was hounded by feelings of depression and anxiety, which I tried to conceal by behaving in a superior yet still modest manner. I was broke again.”3

We were cold, strangers? Isn’t that poetic? Were they cold because of the wind, or were they cold inside? Were they cold separately or together? Were they strangers to Stubnya, to the restaurant, or to each other? At the end of the sentence, the adjective broke is used; in the original Hungarian version, Csath wrote nimolista, a word that has since gone extinct and can only be found in archaic dictionaries, its meaning preserved: in poor financial standing, down on one’s luck, unfortunate, a no-man, a niemand. That is what Csath felt like, and he was not above disclosing it. A few paragraphs later, he writes, “During this time, I excessed moderation with the poisons. On average, I used 02-03 of P every other day at two in the afternoon, in a single dose. It did not produce harmonious euphoria, but it was necessary to quell sexual desire and allay my constant financial and moral worries. I was rightfully afraid that the saison would never really arrive. I saw no goodwill anywhere, I felt no warmth, no attraction.”4 The honesty with which Csath explains his reasoning behind the drug abuse does nothing to interfere with his quantifying of the addiction: how much, when, where, why. But the why is also loaded with a deeply sorrowful understanding of the fact that in his eyes, the world lacks warmth, it lacks goodwill. Here he disregards what he largely uses as a justification, a way of explaining why he became an opium-addict – to push himself to the breaking point and observe what happens there in the name of science – in favor of a more real, more somber explanation: that the world is bad. The condition the humanities have been grappling with since the dawn of culture is what, admittedly, pushes Csath to shoot up or smoke up, time after time; that there is no love, no attraction, no sympathy, that the world is a cold place full of disregard. That it might be impossible to exist in such a place. That even if it is possible, it might not be worth it. This reasoning would not hold its weight as a scientific argument of any sort, whether in casual conversation, research, or a publication. Why do you take drugs? Because I’m sad. But Csath allows this human detail to sneak its way into his observations, because, as he knows, nothing is ever divided into neat particles, me and you, black and white, right and wrong, callousness and love, art and science. He became an addict to experiment with and record his most reliable subject – himself and his own body – but also to grapple with the intensity, the unbearableness, the at-times-joy, at-times-horror of being alive, of being him, of being. Which part of that is science and which part of that is art? Is the personal and subjective innately more connected to the humanities, while the objective and observable is automatically scientific and medical? Are our experiences, thoughts, and lived truths really that easily categorized?

As young medical students and aspiring doctors pledge their alliance to Hippocrates, they are reminded of his insistence that the love of medicine and the love of humanity are linked. One cannot exist without the other, but indeed, perhaps a more relevant question to ask would be whether there is a need to talk about two separate unities to begin with – whether the binaries of art and science, poetry and medicine are innate, or whether they are, quite subconsciously, enforced and upheld by us, simply because we so insist that they exist. Is there a distinction? Need there be one?

Geza Csath lived his whole life in a way that united art and medicine, suffering and the joy of life, addiction and sobriety, creation and despair. If we are able to see just how blurred the lines separating these concepts are, then we are well on our way to seeing how little separates us, as patients and doctors, as cases and solutions; and then perhaps we can all look within ourselves and find our insides, intestines and thoughts, muscles and memories, visions and contractions – all inextricably intertwined.

References

- Szallasi, Arpad. “The gleam and tragedy of Geza Csath (1887-1919).” Orvosi Hetilap 150, no. 48 (November 2009).

- Szasz, Thomas. “The Ethics of Addiction.” The American Journal of Psychiatry 128, no. 5 (November 1971): 541-46.

- Csath, Geza. The Diary of Geza Csath. Translated by Peter Reich. Angelusz & Gold, 2004. 25

- Csath, Geza. The Diary of Geza Csath. Translated by Peter Reich. Angelusz & Gold, 2004. 28

GERDA KOVACS is currently based abroad in Aalborg, Denmark, where she is working on a research project concerning the use of cognitive behavioral therapy and its implications among psychotic patients. She is interested in the intersections of literature, politics and medicine, and has been a guest speaker on multiple panels about the medical humanities. In the future, she is planning on contributing to more research-based projects as well as producing more literary essays.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply