Ashley Austin

Charlottesville, Virginia, United States

|

It was my second month of trauma surgery and the deer-in-the-headlights look had not completely faded. I sat in the surgery resident lounge area finishing up some post-operative notes. The trauma pager and walkie-talkie weighed heavily on my hip. It was not the physical weight, but the weight of anticipation they held. I would have been more comfortable were it only physical weight. I was physically strong, having trained for sports since the age of ten, but I knew well that what the night held for me would be a different kind of test. After browsing for tolerable ringtones, I quickly switched my pager to “vibrate” after realizing I would never be physically separated from it long enough to ever need the ringtone. The anticipation was suffocating. As I fought off fatigue with music and travel searches, I came to the realization that I would not be going home for Christmas this year.

I had never spent Christmas away from my family, and there was something about it that I needed. It was almost as if the naïve positivity surrounding my training recharged me and made me feel that maybe things were not as bad as I made them out to be. For my family, doctors were heroes who never had to endure struggle. People often forget that in any heroic tale many challenges must arise before giving purpose and necessity to a hero. I always thought that if my family had seen the things that I had seen, they would look on me differently, likely with eyes of pain and sorrow. I knew I was being changed in a way that I would not recover from. These experiences would leave heavy imprints on my heart.

My thoughts were interrupted by a familiar buzzing against my hip, followed by a voice over the trauma walkie-talkie saying, “Level One trauma, six minutes out, trauma team please acknowledge.” The familiar sound of my attending physician and chief resident soon followed in words of acknowledgement. My chief and I scurried down the empty hallways, down the stairs and into the emergency department, arriving at the trauma bays. We were met by our attending and the ED staff assembling items in all three bays. Three gurneys appeared in line, one after another. One carried a teenage boy, his face shocked as he reached desperately for the place where a piece of his small intestine leaked out of a large defect in his abdomen. Blood pooled into the sheet as an emergency worker struggled to apply pressure to the gunshot wound. He was rolled into Trauma Bay 1. I blinked once to confirm what I had seen and was abruptly confronted by the reality of what was unfolding in front of me.

To my surprise, my legs engaged with the ground and I moved quickly to secure my cap, gown, and face shield. It was then that I found myself as the only physician in Trauma Bay 3. All eyes were on me. This was maybe the only time in the history of my short medical career that I wished there was some self-identifying information on my ID badge other than “Ashley Austin, MD, surgery.” They must have known that I was only an intern. Right? Their strong anticipatory stares did not give them away. As I made a half turn to retreat and look for my chief resident, the gurney being thrust into the room nearly crashed into my abdomen. Something a colleague once told me rang through my head. “The beauty of trauma critical care is that without you, death is certain, but with you, it is not. You hold this power.”

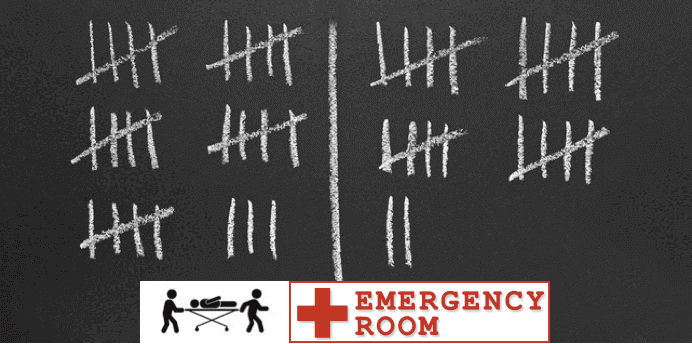

Ready. Set. Go. 1, 2, 3, lift. 1, 2, 3, roll. My brain raced and my hands tried desperately to keep up. Do we have pulses? Let’s secure an airway. Please remove his top and pants. Gunshot wound to the right leg. Open tibia fracture. Check leg pulses. Right leg. None. Doppler. Still no pulse. Page orthopedic surgery. Page vascular surgery. As the surgery teams pushed the gurney away, I sighed. My first solo trauma had been a success, but my stomach still felt tight and I knew something was off. My head was spinning. Having enough time to finish a trauma code solo meant only one thing: where were the others? As I pulled off my gown, I peered into Trauma Bay 2. My chief was placing an arterial line on the patient. My eyes darted to the vital screen. Stable. Of course. Otherwise, the room would be chaos. She had the situation under control. I sighed again, releasing my abdominal muscles and, at the same time, realizing that I had been holding my breath for some time. I felt the pressure in my head dissipate. “Is there something I can do?” I offered. She held her hands and instruments steady as she looked up. Beads of sweat were forming on her head. The overhead light was undoubtedly hot. Her eyes met mine, “Check Trauma Bay 1 and update the family.” Happy for the opportunity to leave this stifling scene, I nodded in acknowledgement and left. As I peered into Trauma Bay 1, I noted several IV poles holding empty bags of O negative blood. Some residual blood was still in the process of settling into the bottom of one of the bags. The mass transfusion protocol had been initiated. I had made many runs to the blood bank, transporting blood to the operating room or trauma bays in the three months that I had been working. I knew well what this meant, and an eerie feeling settled over me.

As I walked down the hallway to the operating rooms, I thought it ironic how quiet the hall could be with just two sets of doors separating it from a likely chaotic and desperate situation. However, in that moment, the white walls gave nothing away. I entered the surgical area, approached the sink, and began scrubbing my hands. I had made it a habit of peering into rooms before entering, especially on trauma nights. It was never bad to know what you were walking into, but on this night I held a deep-seated fear that I might see something that would keep me from ever opening the door. I still had an out. I could easily tell the family that the patient was still in the operating room and I had no further details, which would be true. I shook my head, ashamed that the thought had even entered my mind. Like it or not, I had been given a job. As I entered the room, both attending physicians had their hands in the abdominal cavity, working with large desperate motions of their hands, their arms billowing in an effort to maintain control. These movements were too gross, not a good sign based on the traditional surgical precision. My heart sank. The attending physicians continued to shake their heads back and forth in dismay, their eyes never leaving the patient. Then their shoulders dropped simultaneously in defeat. One attending looked up at me apologetically and said, “We couldn’t save him.” I watched in agony as a deafening silence engulfed the room. “I’ll talk to the family,” said one of the attending physicians. “Austin, would you mind joining me?” His eyes were heavy in desperation and I thought I saw a tear forming. Thereafter, all I saw was emptiness. “Sure,” I replied.

The setting: I would pick anyplace but here. My character: a role nobody would ever choose. The conflict: bad news, a gut-wrenching task. There is nothing like a mother’s love. The hallway is too long and the walls too narrow. Our body language gave us away. She screamed, then collapsed. That scream, the scream of a mother’s loss, echoed through the cold walls. I replay that scene in my head to this day and remain humbled by moments like this that have shaped my resiliency as a physician. Each day is comprised of wins and losses; however, win or lose, I have come to embrace the uncertainty that each day holds. I remain invigorated knowing that no day will be like any one before it.

ASHLEY AUSTIN, MD, is a family medicine chief resident at the University of Virginia Hospital. She has a degree in biochemistry from the University of Evansville in Indiana where she also played college basketball. She attended the Medical College of Georgia and will be pursuing a fellowship in primary care sports medicine.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Personal Narratives

Leave a Reply