JMS Pearce

Hull Royal Infirmary

|

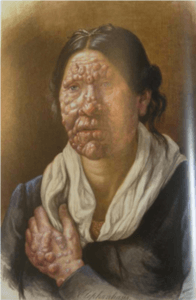

| Fig 1. Patient at St. Jørgen’s Hospital |

Leprosy was the first proven instance of a bacterium causing a human disease. Along with plague, poliomyelitis, and smallpox, leprosy has beleaguered mankind for millennia, causing devastating and often fatal infections that were historically impossible to cure or prevent. The nervous system, skin,and eyes are the main sites affected.

The word is from the Latin lepra, a non-specific scaliness, derived from λέπρα, denoting scaly skin diseases. The biblical word tsara’ath, often translated “leprosy” does not specifically refer to leprosy but rather to other diseases with a scaly skin, such as psoriasis, scabies, and syphilis. We read in Leviticus 14: This shall be the law of the leper in the day of his cleansing: He shall be brought unto the priest: and in the New Testament Matthew 8:3: And Jesus put forth [his] hand, and touched him, saying, I will; be thou clean. And immediately his leprosy was cleansed.

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, an acid-fast intracellular organism not yet cultivated in vitro. It remains a worldwide problem, with high prevalence in Brazil, India, and Indonesia. At the end of 2016 the global prevalence was 0.23 per 10,000 population with 171,948 leprosy cases receiving treatment. During that year 214,783 new cases (2.9 per 100,000) were reported globally, but under-reporting is likely. The use of multidrug therapy (MDT) can cure the individual case, but means of prevention have failed to eliminate new cases. Transmission is probably by nasal mucosal droplets. The incubation period is usually between two and ten years. Once wrongly believed to be highly contagious, many early cases thought to be leprosy were confused with syphilis and tuberculosis, with which it can coexist.

The main clinical features are skin and peripheral nerve lesions causing anesthesia and weakness with characteristic trophic changes and deformities. Neuropathy occurs both in untreated patients and in those on chemotherapy. Treatment withdrawal may be associated with erythema nodosum leprosum reactions. Visual impairment or blindness is frequent, resulting from mycobacterial infiltration of the anterior segment of the eye or from trophic changes of trigeminal and facial nerve lesions Because skin smears are not always reliable, in practice most leprosy classifications use clinical and immunological criteria.

History

Interpretations of the presence of leprosy have been deduced on the basis of descriptions in ancient Indian (Atharva Veda and Kausika Sutra), Greek, Roman, and Middle Eastern documents. During the Chinese Han, Jin, and Tang dynasties, spanning 206 BC to AD 907, there were many vivid descriptions of symptoms and treatments for leprosy.

Using comparative genomics, in 2005 geneticists traced four strains of M. leprae with regional localizations. This confirmed the spread of the disease along migration and slave trade routes taken between Africa, India, Europe, and the New World. The disease was probably brought to the Mediterranean coast by the warriors of Alexander the Great returning from his Indian campaign in 327–326 BC. Leprosy had been unknown in Greece and the Western world before this historic event.

The oldest documented skeletal evidence suggests the disease was present in India by 2000 BC. Skeletal material of the Indus Age suggests that leprosy reached India from its origins in Africa, possibly during the third millennium BC, a time when there was substantial mixing of populations throughout Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Excellent clinical descriptions of leprosy existed in India (c. 600 BC).

Although retrospectively identifying descriptions of leprosy-like symptoms is difficult, Aretaeus (AD 81–?138) gave a classical account of Elephantiasis Aretaei, or nodular leprosy. A later case was verified by DNA taken from the shrouded remains of a man discovered in a tomb next to the Old City of Jerusalem, dated by radiocarbon methods to 1–50 AD. Two North African Coptic mummies dating from the fifth century AD furnished evidence of leprosy in bones. No signs of leprous bony abnormalities were found in 1,844 Egyptian skeletal remains from 600 BC to AD 600, nor in 695 skeletons from Lachish (near Jericho) dated from about 700 to 600 BC. But in 1953 at a medieval monastery near Nestved in Denmark hundreds of skeletons (from about AD 1175 to 1544) showed unmistakeable changes of leprosy. Consistent erosion of the anterior nasal spine and the alveolar process of the maxilla, called facies leprosa or the Bergen syndrome, were noted in these remains and are now thought to be pathognomonic of leprosy.

For centuries leprosy was feared because of its contagious nature (though this was exaggerated) and the disfigurement it caused. It was believed to be highly contagious and was treated with mercury—as was syphilis. Many cases thought to be leprosy were confused with syphilis and tuberculosis. The diseases commonly coexisted.

Patients affected were confined in strict isolation from their communities, often in inhumane conditions. Throughout the world leper colonies, leprosaria, sanatoria, or asylums were created. By 1225 there were around 19,000 in Europe. In medieval England, at least 345 hospitals were wholly or in part for lepers. In 1816 Johan Ernst Welhaven (1775–1828) exposed the shameful living conditions at the four-hundred-year-old St. Jørgen’s Hospital in Bergen as a “graveyard for the living,” but humane reforms were slow to materialize.* These social strictures have lessened since the development of effective treatments in the twentieth century.

|

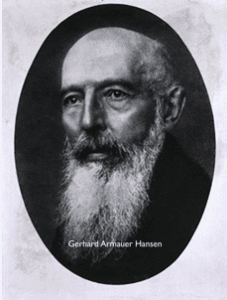

| Fig. 2 Hansen |

Hansen’s bacillus

The causative agent of leprosy, M. leprae, was discovered by Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841–1912) (Fig 2.) at St. Jørgen’s hospital in Bergen in 1873. It was the first bacterium identified as causing human disease. After Hansen’s discovery, new laws in Norway in 1877 and in 1885 once again required lepers to be isolated to prevent spreading the disease to others. Many were confined for a lifetime. This was confirmed in 1897 at the First International Leprosy Congress.

|

Treatment

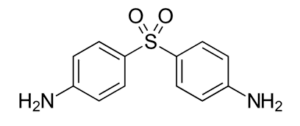

The first effective treatment (intravenous promin) became available in the 1940s. In 1945 Robert Greenhill Cochrane (1899–1985), a renowned British leprologist, studied sulfone derivatives and was the first to use dapsone (diamino-diphenyl sulfone) in the late 1940s.

Dapsone

The search for other effective drugs yielded clofazimine and rifampicin in the 1960s and 1970s. Later Shantaram Yawalkar and his colleagues formulated a treatment for multibacillary patients consisting of dapsone and clofazimine.

Because the incidence of leprosy has declined slowly and the disease is now rare in most industrialized countries, many sanatoria and asylums worldwide have closed. But leprosy remains a major problem in developing countries, where thousands of new cases are diagnosed each year. Further preventive and therapeutic measures must continue if the leprosy scourge is to be eradicated.

Note

* Victoria Hislop’s 2005 novel The Island gives a moving description of the lives blighted by leprosy in the leper colony (1903–1957) at the Cretan island Spinalonga.

Selected bibliography

- Timeline (List) | International Leprosy Association – History of Leprosy Leprosyhistory.org/timeline/list.php

- Monot M, Honoré N, Garnier T, Araoz R. et al.”On the Origin of Leprosy”. Science 2005;308 (5724): 1040–1042.

- Browne SG. How old is leprosy? Br Med J 1970;3: 640–641.

- Grzybowski, A., Kluxen, G. and Półtorak, K. Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841–1912) – 100 years anniversary tribute. Acta Ophthalmologica 2014;92: 296–300.

- Rodrigues LC, Lockwood DNJ. Leprosy now: epidemiology, progress, challenges, and research gaps. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:464–70.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP Emeritus Consultant Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hull Royal Infirmary

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 3 – Summer 2018

Fall 2017 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply