Robert Craig

Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

|

|

|

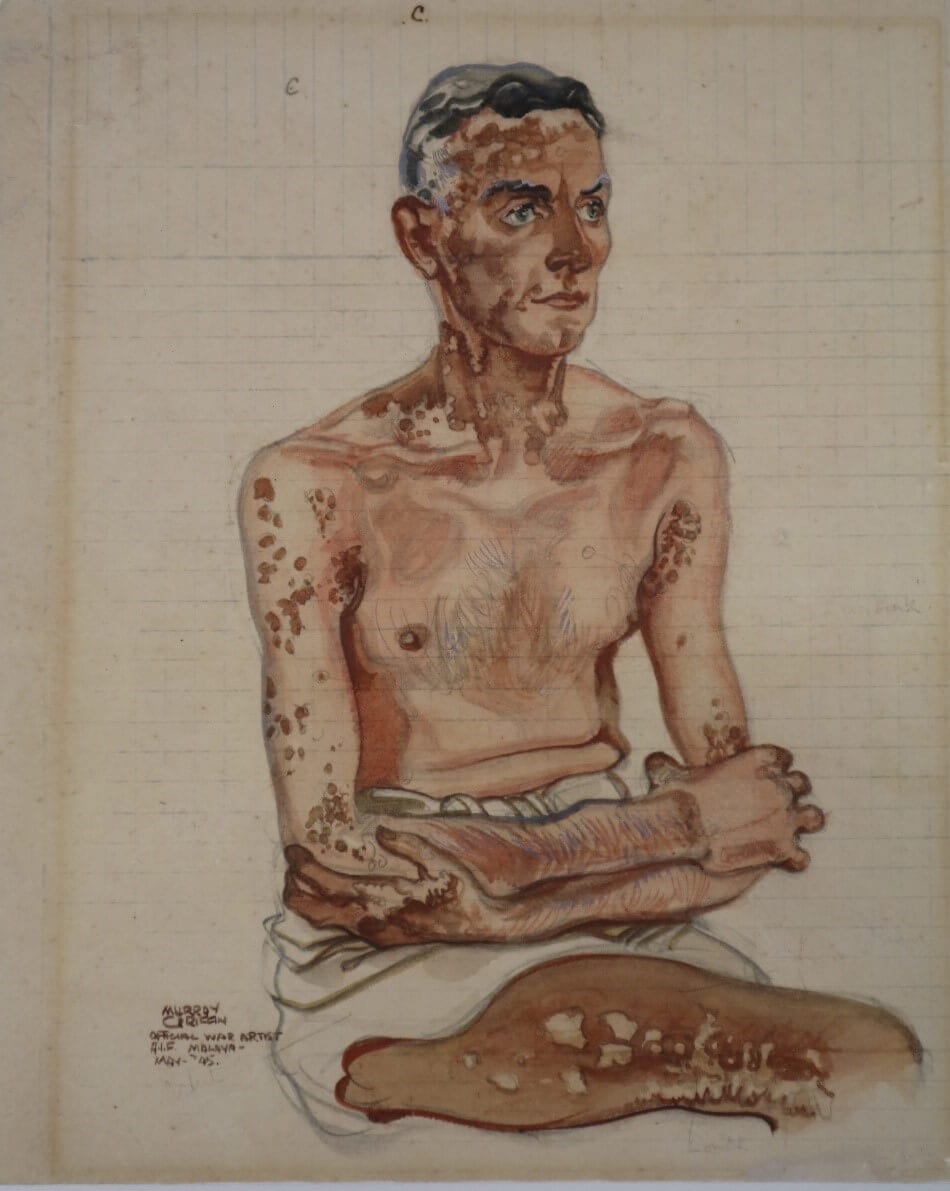

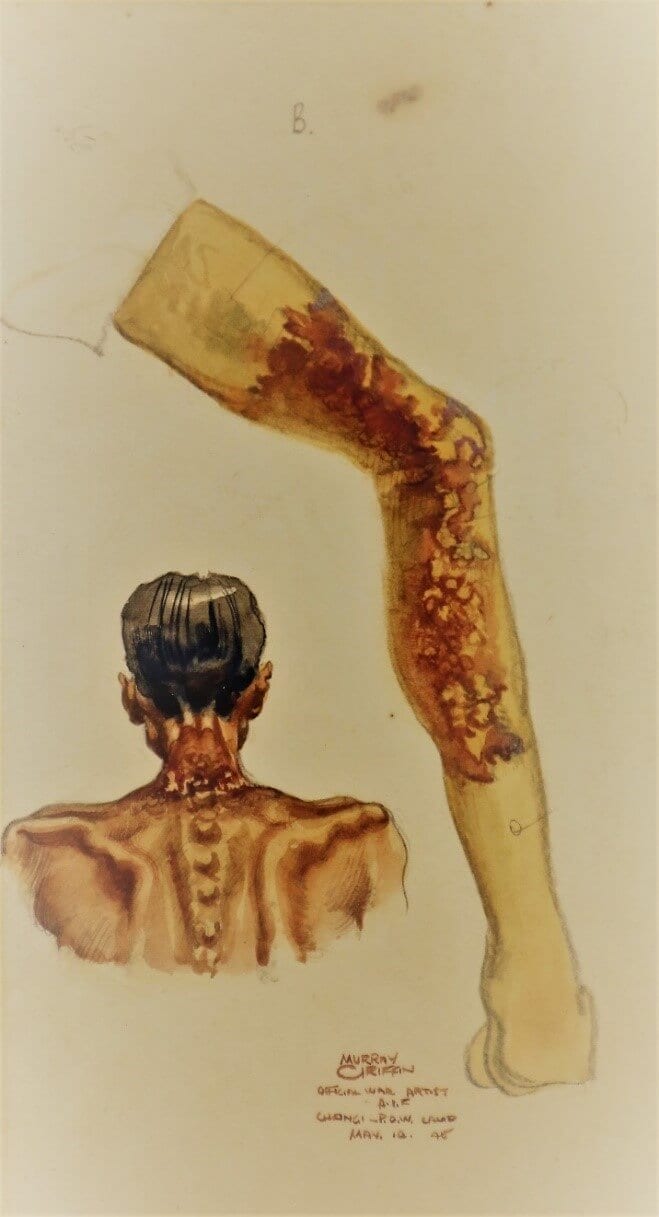

| Malnutrition, Pellagra (left), Tropical Ulcersa, Avitaminosis (middle), Glossitis, and Solar Dermatosis (right) in Australian prisoners of war. | ||

Three paintings and a diary in a handwritten exercise book are in the collection of the Marks Hirschfeld Medical Museum in Brisbane, Australia. They represent an episode of extraordinary courage, survival, cooperation, and perseverance by two prisoners of war (Vaughan Murray Griffin and Dr. Burnett Clarke) during World War Two (Clarke 1989).

Vaughan Murray Griffin was brought up in Melbourne. He trained at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School and taught at Scotch College and Melbourne Technical College. In 1941 he was appointed an official war artist and given the privileges of a captain in the Army. By then he was thirty-eight years old and an established landscape and graphic artist who often used birds and animals as his subjects. His deployment in late 1941 to the Far East was expected to last for only three months but the Allies were already retreating down the Malay Peninsula. Their defeat by the Japanese resulted in Murray Griffin being held as a prisoner of war for three- and- a- half years in Changi Prison in Singapore. His officer status exempted him from forced labor, so he sketched and painted with any material he could acquire.

Dr. Burnett Clarke was a Melbourne graduate who moved to Queensland in 1922 to work at Mater Hospital in Brisbane where he was influenced by the pioneering radiologist Dr. A. T. Nesbet. He decided to specialize in the new discipline and was given the opportunity to study first at University College Hospital in London and then at Cambridge University under Sir Ernest Rutherford. In 1923 he gained further experience at the Mayo Clinic in the United States before he returned to Brisbane to open a private radiology practice with honorary hospital appointments. In the 1920s and 30s, radiology included both X-Ray imaging and radiation treatment, so Clarke gained familiarity with the manifestations of the many skin diseases treated with irradiation at that time. When he was captured by the Japanese in 1942 as an enlisted Captain in the Australian Army Medical Corps, his knowledge of dermatology meant that he was able to act as dermatologist for Australian personnel in the camp. This was a position of utmost importance because skin diseases were causing high morbidity and mortality in the dire physical conditions existing in Changi and the labor camps in Thailand.

|

|

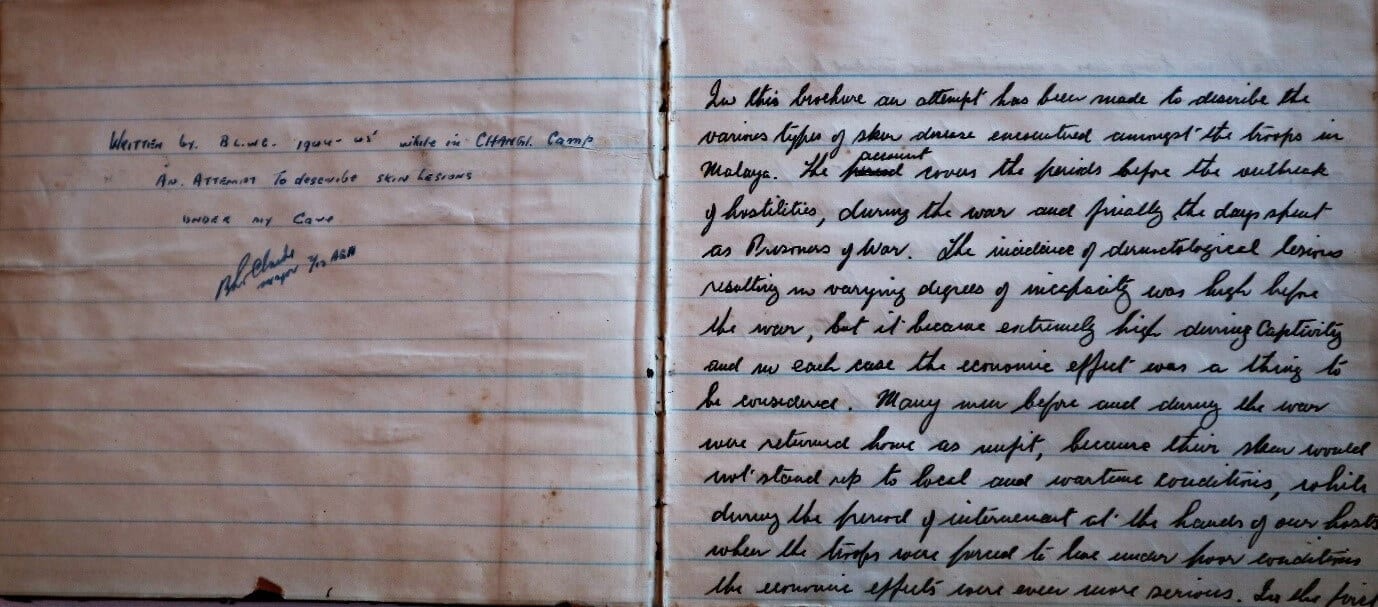

The first introductory pages of “The Clinical War Diary of Dr. Burnett Clarke”. Signed and dated by Major Burnett Clarke (1944-45). |

Dr. Burnett Clarke kept a clinical diary written in a stolen Japanese Army notebook. A distinguishing feature of this diary was his cooperation with an established artist imprisoned with the surrendered troops, Murray Griffin. Besides many vivid charcoal sketches of camp life, Murray Griffin painted detailed pictures of the skin diseases described by Burnett Clarke. After supplies were exhausted, his medical illustrations were painted at risk of severe punishment on the backs of gaol documents. Between February 1942 and September 1945 he used improvised pigments made from plants and medicines such as gentian violet and methylene blue. These pictures were hidden and returned to Australia after liberation. Most of Murray Griffins’ drawings were distributed through private and official collections and many are held in the Australian War Memorial Museum. Dr. Burnett Clarke was closely associated with Brisbane, so three paintings and the clinical war diary were presented to the Faculty of Medicine in the University of Queensland and are preserved in the Marks Hirschfeld Museum.

The coincidence of these two exceptional men collaborating in such unusual circumstances gives special significance to these items as well as a focus for discussion. First, why were they produced at all? Both men worked to record the daily life they experienced. Murray Griffin continued in his appointed duty to memorialize the Army’s circumstances. Burnett Clarke took the opportunity to systematically describe the evolution of skin disease under conditions of starvation in a coastal tropical situation, improvised treatments, and patients’ responses (Clarke 1989). Both men acted in the interest of others beyond their own needs, which showed in their unassuming demeanor after liberation. Burnett Clarke was dismissive of his bravery and Murray Griffin showed the same disposition in a published interview (Gleeson 1979). However, there may be another, less conscious explanation, one which Victor Frankl described in Man’s Search for Meaning, his autobiographical account of life and death in Nazi extermination camps. Frankl described the presence or absence of hope as critical for a future, and observed that while loss of faith resulted in rapid decline and death, kindness and decency to others without self-pity strengthened the will to continue (Frankl 1984). Burnett Clarke and Murray Griffin chose an altruistic activity that gave meaning to the struggle to survive, which spread to everyone who was involved in their effort.

It may require as much as a full generation to pass before shared traumatic memory can be openly discussed. Perpetrators, observers, and victims usually protect themselves with silence and the public appetite for detail is often slow in its demands until experience can be slotted into a more distant connection and cognitively metabolized as history. My own childhood years in England were dominated by men and women who had served and experienced privation in two World Wars. I have also met people who suffered in the Japanese camps, both in the place where I was brought up and in the two districts in which I practiced family medicine. Almost without exception, these people refrained from talking about what happened except in platitudes or humorous anecdotes. My interest in drawing attention to the diary and paintings tries in a small way to influence the way such events are remembered. My generation has doubts as to how we would have behaved in the face of such circumstances and a range of other less admirable emotions, including pleasure that we avoided such pain, voyeurism, and a lack of gratitude for their sacrifice. Without the National War Memorial, art galleries, and museums, these paintings, the clinical diary, and similar items are at risk of being lost or destroyed. Such an event would disrespect their creators, diminish our humanity, and lose valuable primary sources for our understanding of the past.

Image Credits

- Malnutrition and pellagra in an Australian prisoner of war. Treatment required bed rest and mixed vitamins from ‘Marmite’ saved after capitulation; Painted by Murray Griffin, at Changi, May 1945. Photographed by the Author in the Marks Hirschfeld Museum in the Old Medical School, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

- Tropical Ulcers and Avitaminosis in Australian Prisoners of War. Painted by Murray Griffin, at Changi, May 1945. Photographed by the Author in the Marks Hirschfeld Museum in the Old Medical School, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

- Tropical Ulcers, Glossitis, Solar Dermatosis and in Australian Prisoners of War. Painted by Murray Griffin, at Changi, May 1945. Photographed by the Author in the Marks Hirschfeld Museum in the Old Medical School, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

- The first introductory pages of “The Clinical War Diary of Dr Burnett Clarke”. Signed and dated by Major Burnett Clarke (1944-45). Photographed by the Author in the Marks Hirschfeld Museum in the Old Medical School, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

References

- Clarke, Burnett L W. 1989. Behind the Wire, the clinical war diary of Dr Burnett Clarke. Edited by Professor Johm Pearn. Brisbane, Queensland: Department of Child Health Publishing Unit.

- Frankl, Viktor E. 1984. Man’s Search for meaning. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Gleeson, James. 1979. The James Gleeson oral history collection. Transcript, Library of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra: PANDORA Archive, 1-29. Accessed November Wednesday 8th , 2017. https://nga.gov.au/Research/Gleeson/pdf/Griffin.pdf.

- Griffin, V Murray. 1946-47. Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by VMurray Griffin While a prisoner of War in the Changi Area 1942-1945. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne: Victorian Government. Accessed November 8th, 2017. digital.slv.vic.gov.au/dtl_publish/pdf/marc/44/2677317.html.

- Loechel, William E. 1960. “The History of Medical Illustration.” Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 48 (2): 168-171. Accessed November Wednesday 8th, 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC200463/.

- Museum, Australian War. n.d. “Vaughan Murray Griffin.” Biography, Australian Government, Canberra. Accessed November saturday 11th, 2017. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P10676838.

ROBERT CRAIG, BA, MB, BChir, MB, DObst.RCOG, MRCGP, FRACGP, worked for ten years in a UK rural general practice and two years as a government medical officer in the Solomon Islands. In 1984, he moved to Queensland, Australia, to join a family practice. After a few years he retrained to work in the psychiatric services, and before retiring in 2005, he was appointed as a clinician in the Queensland Centre for Intellectual and Developmental Disability in Brisbane. Since 2007 he has volunteered at the Marks Hirschfeld Medical Museum in Brisbane.

Fall 2017 | Sections | War & Veterans

Leave a Reply