Tova Chein,

Mark Epelbaum,

Robert Stern

New York, New York, United States

Introduction

Historically, Jewish contributions to public health measures have not been given adequate attribution. The previous article in this series (Hektoen International, Winter 2016) documented the ancient Jewish recognition of the importance of:

- isolation of individuals with an infectious disease (leprosy, and a more probable translation from the Hebrew, small pox), probably the first public health measure in recorded history

- tuberculosis as an infectious disorder, transmitted to humans from tuberculous cows.

The ritual washing of hands

There are many forms of washing identified in the Bible and Rabbinic commentaries. The ceremonial washing of hands among the priestly class occurred before performing the rituals of the Temple in Jerusalem.

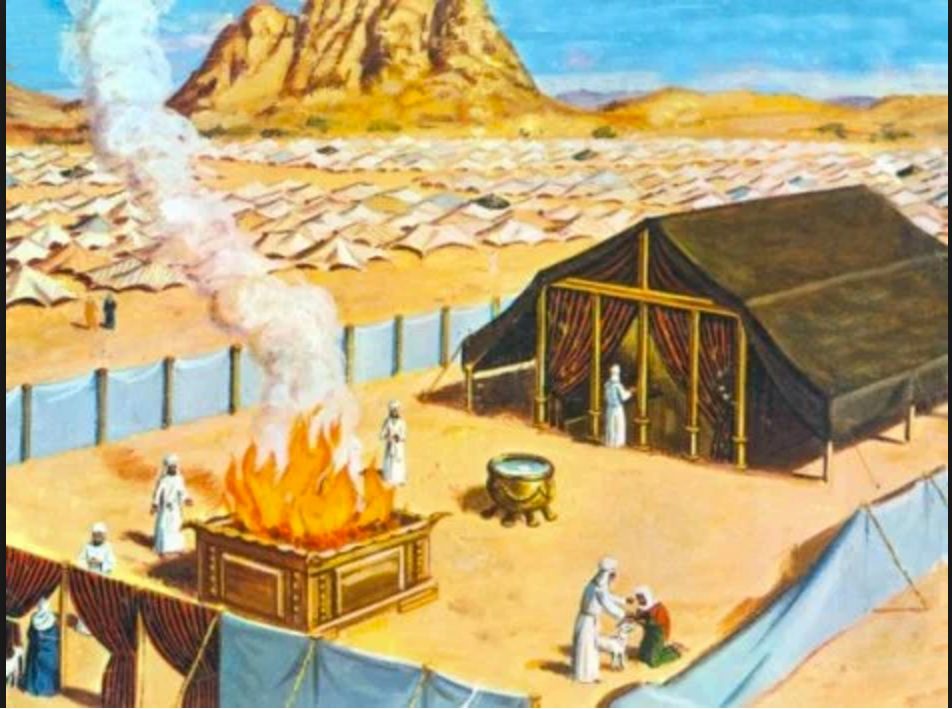

The washing of hands made them ritually pure, but it has an even earlier history (Figure 1) found in the Old Testament, Exodus 30:17-21, while the children of Israel were wandering in the desert.

Moses was commanded:

“You shall make a laver of bronze and place it at the entrance to the tent of meeting”

so that Aaron and his sons could wash their hands before approaching the altar to offer sacrifices. (Figure 2).

“…and it shall be for them a statute forever.”

It is Aaron, his sons and their descendants that constitute the priestly class. These are often designated by their surnames, and can be recognized to this day: Kohen, Cohen, Cohn, Kahn, Kahan, Kogen, Kaplan, Katz (a compound name, a combination of Kohen and tsadick, a righteous Kohen) etc.

When the second Temple was destroyed in AD 70, the dining table in private homes came to represent the Temple altar in Jerusalem. This occurred as Judaism was transformed to become a portable faith that no longer required a physical Temple in Jerusalem. The washing of hands before a meal came to signify the ritual ablutions that occurred in Jerusalem in preparation for animal sacrifices.

Codification of hand washing

Reference to this ritual washing of hands before a meal, referred to as “netilat yadayim,” is found in the Bibleand is elaborated upon in the Mishnah and the Talmud. It was further codified in various forms: by the Spanish physician Moses ben Maimon (1135–1204), better known as Maimonides, in the Mishneh Torah in the 12thCentury, and in the Shulchan Aruch (The Prepared Table) by Joseph Karo (1480–1575) in the 16th Century.

Further codification and condensation was the work of Shlomo Ganzfried (1804-1886) in the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch (The Shortened Prepared Table) in the 19thCentury.

It is also a custom to wash hands again at the conclusion of a meal, referred to as “mayim achronim.” The explanation given is that a layer of salt develops during the consumption of a satisfying meal, representing a crust of indifference. Washing hands symbolizes the removal of such complacency and reminds all at the table of the less fortunate that have not been privileged to partake of such a meal.

The cleaning of the home: Passover and the Black Plague

The thorough cleaning of the home prior to the Jewish Festival of Passover, or Pesach, was performed in order to remove all traces of leavened bread and fermented foodstuffs, known as “chometz.” This is the original “springcleaning.”

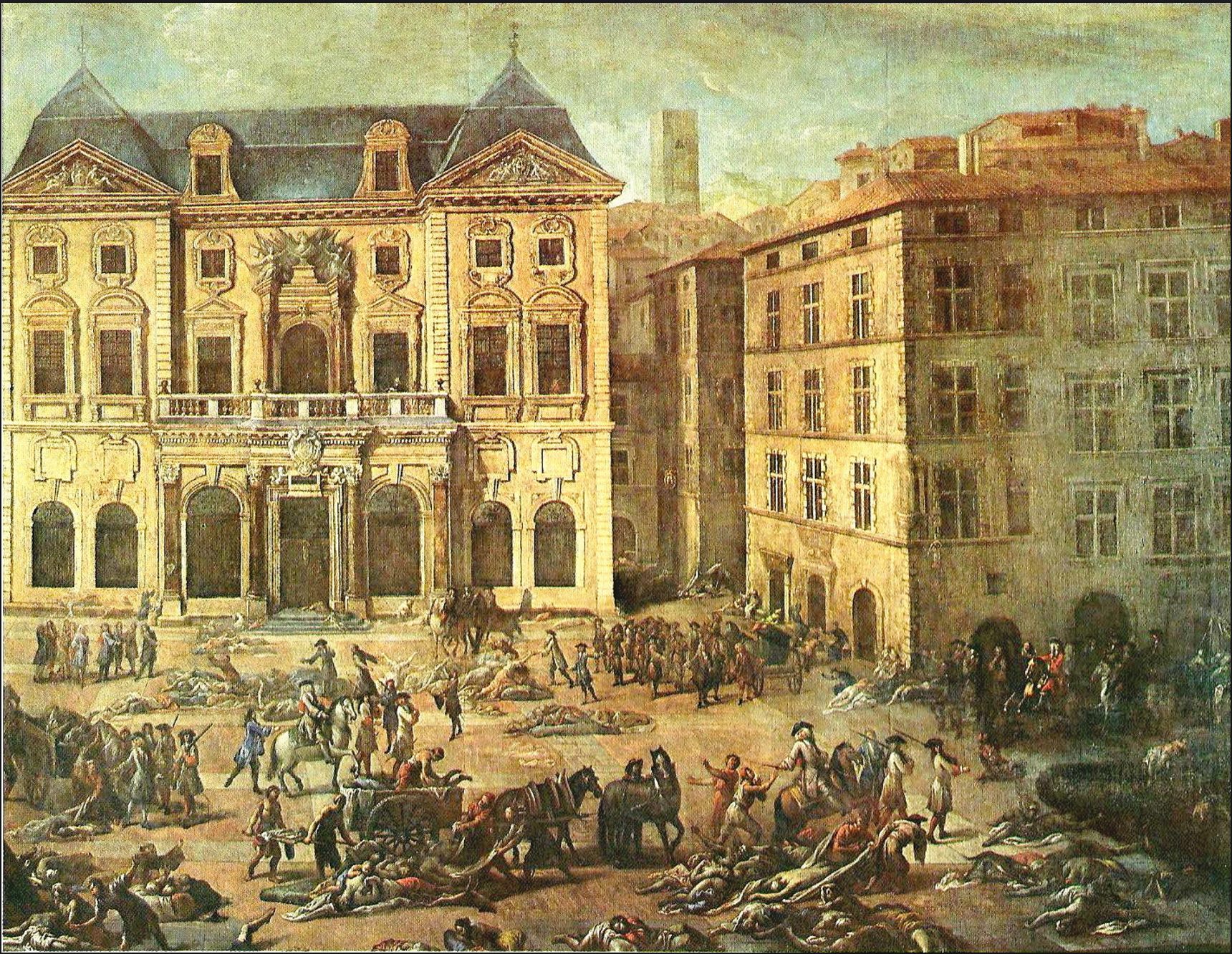

Jewish homes were not as affected by the Black Plague that decimated the population of so many European cities during the Middle Ages.1 It is estimated that a quarter of the population of Europe perished because of the Black Plague. Less dirt attracted fewer rats, decreased the numbers of fleas brought by rats, and therefore reduced Yersinia pestis, the flea-transmitted bacterium that causes bubonic plague. (Figure 3)

The Plague may have started in the Middle East and then went on to Asia Minor. By 1346 it had reached Italian port cities such as Naples, Venice and Genoa, where it decimated the population. Because of the lower incidence of Plague among the Jews, they were falsely accused of poisoning the wells, a conspiracy theory that persisted for centuries. This became transformed ultimately into the “blood libel” accusations against the Jews. These became more vehement around Easter time, corresponding to the Passover season.

Fear was so intense that many of the Jewish communities in France were massacred even before the arrival of the Plague.1 Anticipation of the disease as it slowly moved north prompted what was assumed to be a preemptive activity, as if slaughter of the Jews would provide some form of protection. In the Spring of 1348, as the Plague was moving north from Italy into France, all the Jews of Narbonne and Carcassonne were dragged from their homes and burned at the stake, even though the Plague had not yet reached these towns. The assumption was that by killing the Jews, wells would be spared from being poisoned, the assumed source of the Plague. Similar excesses took place in Switzerland and in towns along the Rhine in Germany.

Ignaz Semmelweiss and the introduction of hand washing into clinical medicine

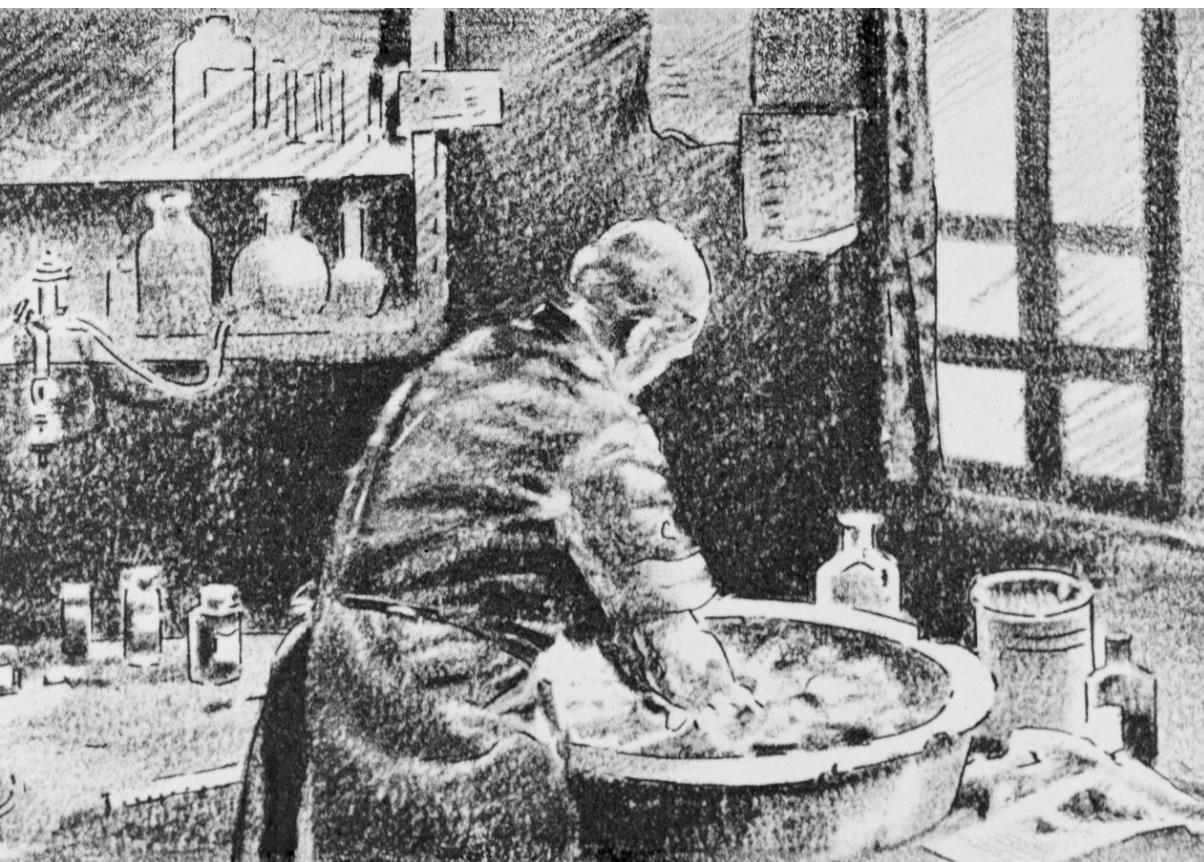

Postpartum infections, also known as puerperal fever, is usually caused by Group A Streptococcus bacteria and was formerly a leading cause of death of new mothers. In Vienna women preferred to deliver at home or in the streets rather than in the revered Vienna General Hospital (known in as the Allgemeines Krankenhaus der Stadt Wien) because of the high rate of infection within the hospital.

(1818–1865) a non-Jewish Hungarian physician working in Vienna decreased death from the disease from twenty percent to two percent by introducing the use of hand washing between patients. He was severely ostracized initially by his peers for advocating for what was assumed to be such a bizarre practice. (Figure 4)

This reflects how little hand washing was practiced in earlier times. This may be in part because water spigots were not customary in homes until relatively recently, particularly in rural areas. Water wells and pumps were located on the street at some distance from individual homes and had to be hand carried for washing and cleaning. Bathing and hand washing were arduous activities. Because of custom, refraining from these practices continued long after water taps were introduced into houses and hospitals.

Semmelweis also proposed, for the first time in medical history, a connection between touching cadavers and a risk of infection. The Jewish regulation that a body must be washed prior to funeral and burial predates this concept by thousands of years.

The Jewish ritual of washing of the body before burial

An important element of a Jewish burial is the “tahara”, the washing and dressing of the deceased body for its final rest. This is considered a ritual purification until the Resurrection of the Dead, hamachayit hametim. The “tahara” is a simple yet dignified ritual that allows the person to meet his or her Maker with respect and dignity. The washing of hands is required by all individuals that have been in the presence of a dead body.

Hand-washing as a current public health measure

Hand washing with soap is currently the single most effective and inexpensive way to prevent the spread of disease. Infantile and acute respiratory infections including pneumonia, are major causes of mortality among children under five years of age. Taken together, they account for almost 3.5 million child deaths annually. Hand washing with soap before eating and after using the toilet saves more lives than any single vaccine or medical intervention.

Handwashing can also limit the spread of various forms of hepatitis, influenza (flu), streptococcus (pneumonia, strep throat), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and the common cold, and those spread through fecal-oral transmission such as salmonella, shigella, giardia, enteroviruses, amoebas and campylobacter.

Conclusion

This tradition of the washing of hands can be traced back to the Biblical era, to children of Israel wandering in the desert in the 14th Century BC. Ancient ritual purification rites derived originally from these very early Judaic concepts and continuously codified throughout Jewish history, predate the current concepts of hygiene and cleanliness by thousands of years.

Reference

- Jacob Marcus, The Jew in the Medieval World: A Sourcebook, 315-1791, (New York: JPS, 1938).

ROBERT STERN, MD, is a board-certified Anatomic Pathologist. He teaches Pathology to medical students at Touro School of Osteopathic Medicine since 2009. He taught at the Al Quds School of Medicine in East Jerusalem from 2007-9. Before that, he was at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) for 31 years where he participated in the teaching diagnostic, research and administrative activities of the Department of Pathology. He also continues to conduct a research program in matrix biology, concentrating on hyaluronan, hyaluronidases, chitin, and chitinases.

MARK EPELBAUM, OMSIV and TOVA CHEIN, DO are currently students at the Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Leave a Reply