James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

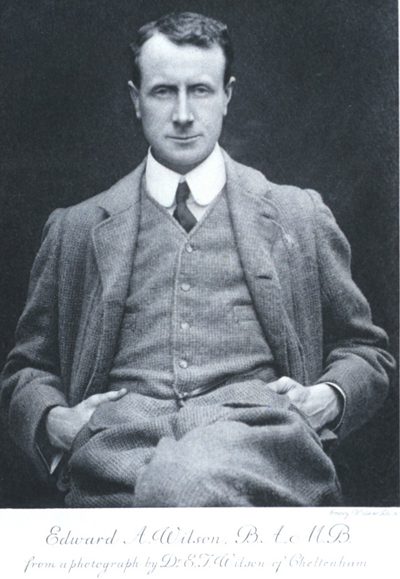

Edward Adrian Wilson

Of the physicians associated with the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, only the name of Edward Adrian Wilson (1872-1912) might be recognized today. He was one of the four men of the Terra Nova Expedition to accompany Captain Robert Falcon Scott on his final dash to the South Pole. After man-hauling sledges 800 miles for over ten weeks, they reached the South Pole on January 17,1912 only to confront the disheartening sight of Roald Amundsen’s flag markers and black tent testifying that the Norwegian expedition had bested them, having arrived a month earlier. On their return journey all five men perished from scurvy, infection, trauma, malnutrition, frostbite, and physical exhaustion. Scott, Wilson, and “Birdie” Bowers were the last to die, in a tent eleven miles from a major resupply depot. It was almost a year before the world would learn of their heroic struggle. For Englishmen following the disasters of the Boer War and the ascendancy of German might their story provided a narrative of courage, self-sacrifice, and patriotism that overshadowed Amundsen’s accomplishment.

Wilson is recognized for his expertise in ornithology and as an artist and physician explorer. He was deeply religious and his religious strength was a great comfort to the men with whom he served. In their letters home and in their personal diaries, Wilson was uniformly singled out for praise during both his first Antarctic expedition aboard the Discovery (1901-1904)and his final journey aboard the Terra Nova (1910-1912). He had a gift for defusing tensions and restoring confidence; and was a trusted and loyal friend to Captain Scott. During the Discovery Expedition, Scott chose Wilson and Ernest Shackleton to accompany him in an attempt to travel as far south as possible on the polar plateau. In no situation were Wilson’s skills as a mediator more severely tested than on this journey. All three men suffered from scurvy; Shackleton more so, and as a result, Scott ordered him home on a relief ship as medically unfit. Shackleton was determined to redeem his reputation and began assembling the Nimrod Expedition of 1907. He sought Wilson’s participation as co-expedition leader. Wilson declined because he was committed to solving the mystery of a disease that was decimating the red grouse population in Northern England and Scotland before English sportsmen had the opportunity to kill them.

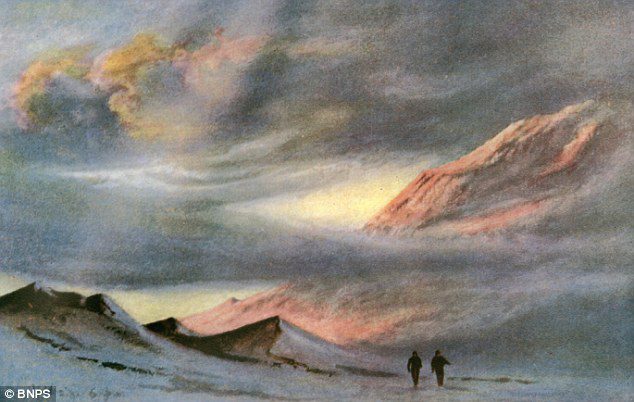

Edward Adrian Wilson was born in Cheltenham, England, on July 23, 1872. Like Frederick Cook, he was the son of a physician. At an early age Wilson manifested both a keen interest in natural history and a remarkable artistic talent. Though self-taught, he had a talent he cultivated throughout his life, using it professionally as a medical illustrator and expedition artist. Wilson was strongly influenced by John Ruskin (1819-1900) and the precepts on art expressed in Ruskin’s 1853 volume The Stones of Venice. Like Ruskin he was a passionate admirer of J. W. M. Turner (1781-1851), whose influence can be seen in the artwork completed during the expedition. In November 1904 his Antarctica paintings were exhibited in the Burton galleries on Bond Street along with 200 photographs taken by the expedition photographer, Reginald Skelton. Wilson’s contribution of 280 items included watercolors of birds, scenic watercolors, pencil drawings, and topographical sketches. The exhibition was a success and was seen by some 10,000 visitors. The public was fascinated by the first ever drawings of emperor penguin chicks. In her biography of Wilson Isobel Williams notes that his watercolor, Emperor Penguin Rookery, Cape Crozier,sold for more than 9,000 pounds at Christie’s in London in 2003 and his Last View of Mount Discovery sold for 5,000 pounds at the same auction.

Wilson began his medical studies in 1894 at the age of twenty-two at St. George Hospital in London. Three years later he moved his lodgings to Caius Mission, serving slum-dwellers of the Battersea area. There he met his wife, Oriana Souper, who was staying with the warden of the mission. The two were instantly drawn to each other and shared very closely held spiritual values. They were married on July 16, 1901, two weeks before Wilson was due to leave England aboard the Discovery. Returning to England in 1904, the couple spent six years together before he joined Scott’s second expedition on the Terra Nova. Their household was modest and in keeping with current trends they did not employ any servants. They had no children and Oriana never remarried after Wilson’s death. Oriana survived her husband by thirty-three years, dying at the age of seventy-two.

Following the Discovery Expedition, Wilson occupied himself with preparing his expedition paintings, lecturing, and completing reports from the voyage. The thought of returning to medicine was not appealing as he had been away from hospital work for too long. In March 1905 he was offered a post as field observer to investigate the grouse disease that was decimating the red grouse population. It was a paid position scheduled to last six months but in the end required five years to complete. It entailed grueling fieldwork and over 2,000 post-mortems on the grouse, a task Oriana willing shared with him. He eventually found that the disease was caused by a parasitic threadworm, Trichostrongylus pergracilis, which dwelt in dewdrops on the heather. When ingested by the grouse, it lodged and ulcerated the bird’s cecum. His work, The Grouse in Health and Disease, appeared posthumously. Wilson had written one third of the report and prepared the beautifully illustrated colored plates. The report and its recommendations on the management of the disease eventually saved the sport and added over two million pounds to the British economy.

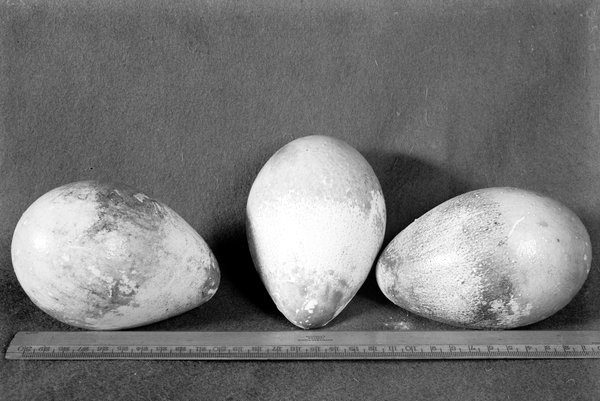

In 1909 Scott asked Wilson to join him as Chief of the Scientific Staff on his second expedition to the Antarctic. Wilson felt it important that he return to the Antarctic to further study the emperor penguins, whose lifecycle remained a mystery. Prior to the Discovery Expedition it had been assumed that all penguins left the Antarctic to breed. The finding of eggs at the Cape Crozier rookery had proved that the species had evolved to reproduce in the subzero temperatures of Antarctica. At the time, birds were thought to have evolved from dinosaurs sharing many unique skeletal features. Wilson wrongly believed that penguins were very primitive birds and that their embryology would provide useful information on their avian origins. The Discovery Expedition had failed to recover eggs suitable for study, and for Wilson this was an important objective in his returning to the Antarctic. In the darkness of the Antarctic winter of 1911, Wilson, Harry R. Bowers, and Apsley Cherry-Garrad made an extremely hazardous sledging journey of sixty-seven miles in blinding blizzards to a penguin rookery hoping to collect eggs at a precise stage of development. They braved winds of eighty miles per hour and temperatures of minus sixty-five degrees Fahrenheit. In the words of Cherry-Garrard: “It was . . . the worst journey in the world . . . the weirdest bird’s nesting expedition that has ever been or ever will be . . . no words can express the horror.” Barely escaping with their lives, they returned to the base camp at Hut Point with three precious eggs. Cherry-Garrard added: “And now the reader will ask what became of the three penguins’ eggs for which three human lives had been risked three hundred times a day, and three human frames strained to the utmost extremity of human endurance” before humorously describing the indifferent reception he received in 1913 when he presented the eggs to the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. Ultimately, the eggs were examined by Professor Cossar Ewart of Edinburgh University and the report was included as an appendix in Cherry-Garrard’s book. The embryos Wilson collected were too developed to test Haeckel’s Theory that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. There were no teeth or scales to connect the birds with reptiles. What Wilson could not know was that penguins were further down the evolutionary tree and had evolved from birds with flight rather than the reverse.

Isobel Williams has reviewed several interesting medical episodes in Wilson’s life and career. In 1897, while still a student and working at the Caius Mission in Battersea, he contracted pulmonary tuberculosis. Treatment was entirely non-specific and included travel to Norway and to Davos in Switzerland. His voyage aboard the Discovery Expedition was almost derailed following a hand infection and a subsequent chronic axillary abscess requiring surgical drainage. Wilson along with Scott and Shackleton all suffered from scurvy during their fifty-two day journey toward the South Pole in 1902-1903. Wilson also survived a severe anaphylactic reaction to a wasp sting when he had returned to England following the Discovery Expedition. The diaries of Wilson and Robert Falcon Scott that were found along with their bodies provide documentation of the travails Scott, Wilson, Henry Bowers, Lawrence Oates, and Edgar Evans endured during their return from the South Pole. Williams notes that Wilson “developed a swelling of his tibialis anterior muscle (his shin) after twenty-two miles of difficult skiing. The front of the leg was swollen and tight, the skin was red and oedematous.” Wilson’s description of the anterior compartment syndrome following strenuous exercise is now recognized in athletes.

When news of the death of Robert Falcon Scott and the men of his expedition reached London, there was a national outpouring of grief. In the presence of King George V, a memorial service was held in London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral. Wilson’s Christian faith and his death on an epic journey made him a “perfect hero” for Edwardian Britain. He was posthumously awarded the Patron’s Medal of the Royal Geographical Society in 1913. A statue of Wilson in polar garb carved by sculptress Kathleen Scott (1878-1947), Scott’s wife, was unveiled in Cheltenham’s Town Promenade in July 1914 and remains there today.

References

- Brown, Kevin. “Edward Adrian Wilson (1872-1912): polar explorer and artist.” Journal of Medical Biography. 2012; 20:169-172.

- Cherry-Garrard, Apsley. The Worst Journey in the World: Antarctic 1910-1913. Published in two volumes, Constable and Company Limited, Great Britain, 1922.

- Swinton, W. E. “Physicians as explorers. Edward Wilson: Scott’s final Antarctic companion.” Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1977;117(8):959-974.

- Schullinger, John N. “Edward Wilson – Explorer, Naturalist and Surgeon.” Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1985;160:373-377.

- Williams, Isobel. Edward Wilson: Explorer, Naturalist, Artist. Gloucestershire, UK: The History Press, 2008.

- Williams, Isobel. “Dr. Edward Wilson (1872-1912): Antarctic Hero.” Journal of Medical Biography. June2009;17(2):111-115.

- Williams, Isobel. “Edward Wilson: medical aspects of his life and career.” Polar Record. January 2008; 44(228):77-81.

- Wilson, D.M. & Elder, D.B. Cheltenham in Antarctica: The Life of Edward Wilson. Reardon Publishing, U.K., 2012.

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Leave a Reply