Fergus Shanahan

Ireland

Edvard Munch

Oil on canvas

Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo, Norway

“Nothing happens. Nobody comes, nobody goes. It’s awful.”

― Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot1

Waiting. It’s an inescapable part of the human condition, perhaps, but it is a big part of the experience of illness. Being ill is being patient. Why otherwise use such a word? “Nobody, not even a lover, waits as intensely as a critically ill patient,” according to Anatole Broyard, in his unsentimental commentary on his own experience with prostatic cancer.2 Patients wait for results, wait for good or bad news, and in many health services, they wait to see the doctor, and a specialist, then another specialist. All patients wait for an outcome. Uncertainty. “I don’t know how this story will end”—a bold declaration by a celebrity after public disclosure of her recovery from treatment for breast cancer.3

Everybody waits. In the 1991 motion picture The Doctor, a skilled and once insensitive surgeon reforms after he develops laryngeal cancer and encounters the bureaucratic inefficiencies of healthcare familiar to many patients, the errors, endless forms for completion, and waiting. Joining the press of human bodies in the waiting area, he expresses his frustration to neighboring patients: “I am a doctor,” to which a young woman suffering with a brain tumor replies: “not when you’re sitting here.”4 Even the privileged and celebrities wait at some phase of their illnesses; everybody waits . . . “we are all, in some sense, in the doctor’s waiting room.”5

Medical waiting rooms differ from other waiting areas. More than a temporary halting site to pass through on the way to another destination, the medical waiting room completes the transformation of a person to a patient. In her essay on the medical waiting room, Laura Tanner refers to “this atypical public space,” which steals some of a patient’s sense of control, poise, and a degree of dignity.6 The configuration of most medical waiting rooms, regardless of décor, she writes, disallows any attempt to establish “personal territory through the kind of purposeful posture and motion that occur so easily even in crowded locker rooms or transit waiting areas.” The medical waiting room renders public the illness which is actually a private, personal condition. The acute self-awareness of the patient waiting is heightened by anticipation of clinical scrutiny of one’s body.

In her introduction to The Poetry Cure, Julia Darling comments on the disempowerment and the helplessness of patients while waiting in the surreal environment of a hospital.7 She restored her own sense of control by writing poems, many of which were begun in the waiting room:

Acute ears listen for

the call of our names . . .

Our names, those dear consonants

and syllables, that welcomed us

when we began,

before we learnt to wait. . . .8

Elsewhere, a physician reflects in verse on the bonds securing a family in a waiting room against the “flood of words and looks.”9 For some, the waiting room is laden with suffering, a vivid separation of the ill from the well, but mainly a place where the poor go.10 The medical waiting room has been assigned a persona unto itself:

I am the room that understands waiting,

With my box of elderly toys, my dog-eared Women’s Owns,

Permanent as repeat prescriptions, unanswerable as ageing,

Heartening as the people who walk out smiling, weary

As doctors and nurses working on and on.11

Another poet relives a childhood experience when she accompanied her aunt to a dental appointment, and while in the waiting room, had a dawning awareness of her own identity, becoming a little frightened of the gravity of her own existence in a world of grown-ups.12 As an adult, the poet recalls the episode and the elements of the waiting room which contributed to a loss of some of her childhood innocence.

Artists have long been intrigued by the stories of illness and have expressed the emotions and context of illness in many forms. There are stories on the faces of patients in waiting rooms. L.S. Lowry captured these in his portrayal of A Doctors Waiting Room (c. 1920) and Ancoats Hospital Outpatients Hall (1952) where lines of patients are arranged on benches like a mechanized conveyor leading to the doctor.13 These images are records of a bygone time, but the scenes presented by Lowry are as familiar and germane today as they were over a half-century ago.

For some, the waiting experience is akin to that of a social gathering, for many it is a solitary experience, and for a few, the anticipation of bad news is written on the faces. Doctors observant of patients in waiting will recognise the stories on the faces immediately. Lowry’s image is almost identical to my memory of the hospital where I trained, and other than the décor, looks much like where I now work. Indeed, a contemporary description of the outpatient department in an otherwise modern hospital is reminiscent of Lowry’s scenes:14 “The place is a maelstrom of patients, relatives, doctors, nurses, secretaries, porters, ambulance staff, students and the occasional dog.” Curiously, it is a place where “examples of senior management species are rarely encountered” except when accompanying occasional “political dignitaries, in anticipation of whose coming, the place has been sanitized and cleansed of all but a few token patients.”

While the experience of illness is individual and personal, the occurrence and facts of illness are universal, and so it is with medical waiting rooms. An untitled photograph by Paul Seawright (c. 2006) of a woman and child waiting in a disheveled clinic in sub-Saharan Africa addresses the difficulties with access to adequate healthcare in many parts of the world, whilst at the same time conveying the apprehension and boredom of waiting. A tired woman who appears to have a weight on her shoulders sits patiently, surrounded by jaded public health posters and boxes, as her child, a toddler, still curious, looks toward the camera.15

“But outpatients are different” according to the poet UA Farnthorpe, who experienced both sides of the divide, including a lengthy spell as an inpatient and later, an outpatient department where she worked as a cleric.16 “They bring their kids with them, for one thing, and that creates a wrong atmosphere. They have shopping baskets and buses to catch. They cry, or knit” and

. . . they haven’t yet learned

How to be reverent.

This is a reminder to her overstretched healthcare colleagues that outpatients are real people with real lives to live.

In contrast, the poet likens hospital admission to an interview with St. Peter at the gates of heaven and addresses Peter (“I reckon, like me, you deal with the outpatients”), sharing with him the observation that the “inpatients are easy” because they are under the control of the nurses and doctors and “know what’s what in the set-up.” Indeed, but inpatients wait in lonely isolation, after visiting hours, when a heightened awareness of body function may peak.

Design and organization of hospitals is often suited more to institutional needs and acute care, with less attention to the needs of the chronically ill. This neglected aspect of the experience of illness is made more poignant by the striking images of the photographer Thomas Struth, which are separately selected for both the head and foot of each bed, to be viewed by caregiver and the patient, respectively.17 Struth concentrates on subjects that might be “missing”—the images of local landscapes and flowers of intense color, details of which are highlighted, reflecting the focal attention given to one part of the body during the experience of illness.

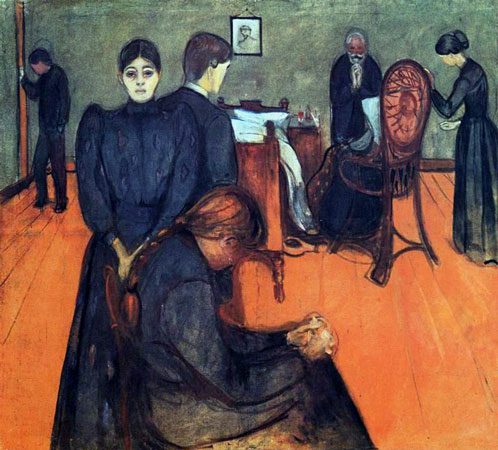

Waiting for death, the final struggle for a patient may also be a harrowing experience for vigilant loved ones and for caregivers. To acknowledge and help assuage the guilt of those who silently wish for the death of a loved one or for another who suffers, the authors of a thoughtful work on the topic used a provocative and telling title: The Welcome Visitor.18 Decay and death have intrigued artists through the ages.19 In a monograph on waiting, the paintings by Ferdinand Hodler of the death of his mistress Valentine Godé-Dorel, are analyzed.20 In these famous images, the sufferer is alone. How should we behave in the face of another’s suffering? The consensus appears to be by saying “here I am” . . . that is, by being there. Dying is what one must do by oneself, but no one should have to die alone.

Has waiting any value? For caregivers, waiting is not always attributable to delay and inefficiency, it may be intentional, a period to allow evolution of illness to clarify diagnosis or treatment. This is watchful or expectant waiting. For the patient, the interruption of time by illness is more than wasted time, it is experienced time. If “too long a sacrifice/can make a stone of the heart”21 and “hope deferred maketh the something sick,”1 a temporary period of waiting provides respite from the non-essentials in life, an opportunity for redirecting attention to our values and relations with others.20 Like the experience of the imprisoned characters in Beckett’s Godot, waiting while ill is always with an element of hope.

References

- Beckett S. Waiting for Godot. Act 1. London: The Folio Society, 2000.

- Broyard A. Intoxicated by my Illness. New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1992, 22.

- Lawlor A. The Experience of Illness. Learning from the Arts. A symposium, University College Cork, National University of Ireland, Nov 30, 2012.

- The Doctor (film) 1991.

- McCrum R. My Year Off. Rediscovering Life after a Stroke. London: Picador. 1998; p234.

- Tanner LE. Bodies in waiting: representations of medical waiting rooms in contemporary American fiction. American Literary History 2002;14(1):115-130

- Darling J, Fuller C (eds). The Poetry Cure. Newcastle: Bloodaxe poetry series:3

- Darling J. A waiting room in August. In: The Poetry Cure, edited by Darling J and Fuller C. Newcastle: Bloodaxe poetry series:3, 20

- Christensen J. The family in the waiting room. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1479

- Lara F. The Waiting Room. http://www.short-story.net/read/1447/the-waiting-room2 (accessed Feb 20, 2013)

- Farnthorpe UA. Waiting Room. In: The Poetry Cure, edited by Darling J and Fuller C. Newcastle: Bloodaxe poetry series:3, 19

- Bishop E. In the waiting room. In: The Complete Poems. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1983,159.

- Rohde S. LS Lowry. A biography. 3rd ed. Salford: Lowry Press, 1999

- Kirwan L. Political Correctness and the Surgeon. Milton Keynes: AuthorHouse 2008, 33.

- Seawright P. Untitled (Woman and Child). 2006. Lewis Glucksman Gallery, Cork, Ireland.

- Delaney P. The hospital poetry of UA Fanthorpe. In: Teaching Literature and Medicine. edited by Hunsaker Hawkins A and Chandler McEntyre A. New York: The Modern Language Association, 2000,267-276.

- Struth T. The Dandelion Room. DAP/Distributed Art Publishers, 2001

- Humphrys J, Jarvis S. The Welcome Vistor. Living well. Dying well. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd.

- Wellcome Collection, Ford K (curator) Death. A Picture Album. London: Wellcome Trust, 2012.

- Schweizer H. On Waiting. Thinking in Action. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2008, 88.

- Yeats WB. Easter 1916. http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/unbound/poetry/soundings/easter.htm (accessed Feb 25, 2013).

Further reading

Man is a waiting animal, George Dunea

FERGUS SHANAHAN, MD, is professor and chair of the department of medicine, University College Cork, National University of Ireland, and director of the Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre, a research centre funded by Science Foundation Ireland that investigates host-microbe interactions in the gut and the therapeutic potential of mining the microbiota. His interests include most things that affect the human experience. He has published over 400 scientific articles and several books in the areas of mucosal immunology, inflammatory bowel disease, and the microbiota and including several articles relating to the medical humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 5, Issue 3 – Summer 2013

Leave a Reply