Dylan Chan Kai Der

Isabella Eleanor Nubari

Singapore

“The butcher’s bill for the Crimean War of 1853-1856 will never be known exactly, but it probably amounted to over 1 million deaths…”

—Robert Breckenridge Edgerton, Death Or Glory: The Legacy of the Crimean War1

In the Crimean War disease killed four times as many soldiers as battle wounds,2 resulting in the deaths of 25,000 British, 100,000 French, and up to a million Russians.3 But to truly understand the significance of these numbers, consider the following eyewitness account, detailing the British base at Balaklava:

If anybody should ever wish to erect a “Model Balaklava” in England… Take a village of ruined houses in the extremest state of all imaginable dirt; allow the rain to pour into them, until the whole place is a swamp of filth; catch about 1000 sick Turks with the plague, and cram them into the houses indiscriminately… and stew them all up together in a narrow harbor, and you will have a tolerable imitation of the real essence of Balaklava.4

This backdrop of death and disease prompted medical innovations on all sides of the war, whose effects continue to shape medical strategy in the field even today. This essay would examine the developments in medical technology and strategy through evolutions in administrative systems, the quality of staff, and the advances in medical technology in Britain and Russia.

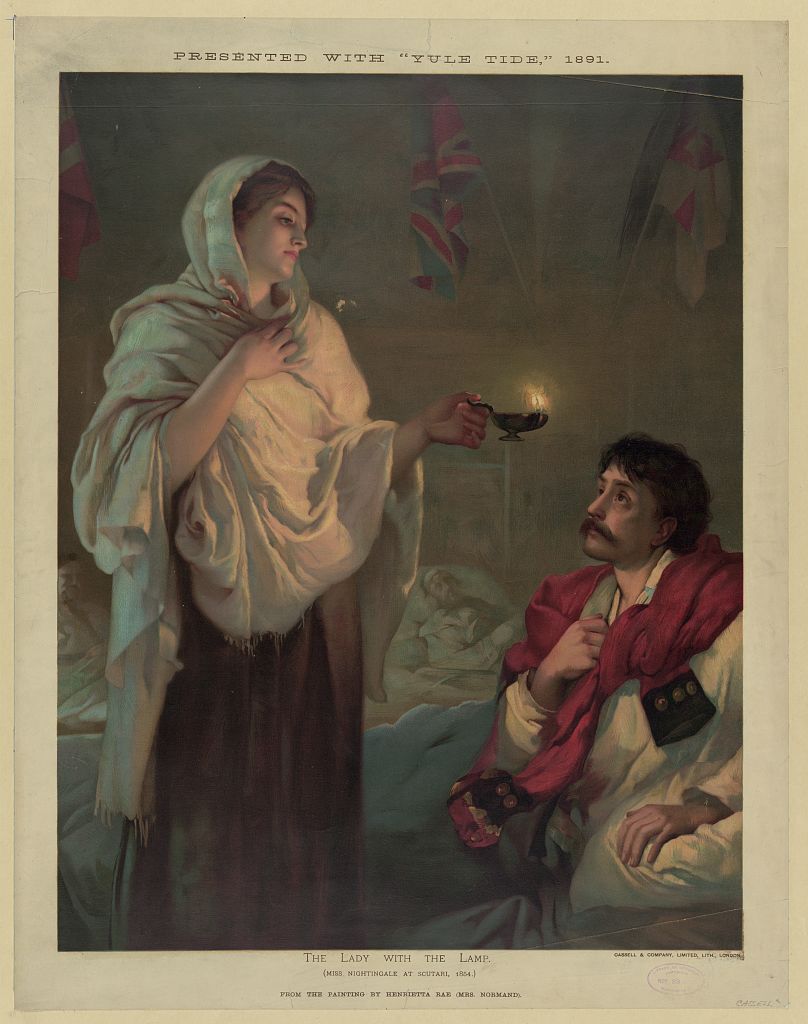

It was in these war conditions that the legend of “The Lady with the Lamp” first began. Florence Nightingale, after landing in Scutari, implemented new procedures such as hand-washing, washing the soldiers, and giving them clean beds. Wounded soldiers were stripped of their sullied uniforms and had their wounds washed before fresh, clean linens were used to prevent cross-contamination. Other innovations were removing the excreta and keeping windows open for air circulation. Measures like these would later be codified in the Sanitation Commission’s report to the Royal Commission. With these reforms the mortality rate in British army fell to almost one-tenth of its previous value.

Medical practices in Russia before the Crimean war were primarily based on homeopathic treatment and the rejection of plaster dressings and anesthetic agents due to haemorrhagic risks. As a result, medical treatments failed to eradicate epidemic diseases among the troops, up to eighty percent of patients died from gangrene, and soldiers with gunshot wounds had amputations with dismal survival rates. The medical strategy before the reforms also favored medical evacuation of wounded soldiers to on-site treatments, resulting in the lack of ready medical assistance.

Prompted by the dire need for medical assistance during the Polish campaign where 85,000 soldiers were wounded or sick, new regulations in the 1830s created a network of field hospitals and station quarters. By 1853 the Imperial Russian Army had fifty-three field hospitals capable of treating 15,000 soldiers, and stock of extra supplies sufficient to treat 12,000 others.

The main failure of the Russian Army, however, was its lack of administrative foresight. The road through Simferopol, sole link between the chief naval base and the mainland, was barely accessible in winter. Military policy dictated that the bulk of medical supplies went to Poland, so local supplies were unable to meet the demands of siege warfare. Furthermore, Tsar Nicholas I’s 1836 reforms fractured the medical service into four departments and two different ministries, hindering logistical coordination. According to Hinton (2015), rampant corruption of underpaid supply officers in a cash-strapped Tsarist government left the medical service in disarray.5

The failure of the administration to protect its soldiers prompted large sums of donations and a great number of medical practitioners and female nurses to volunteer. Among them was Professor N.I Pirogov, who as a field surgeon introduced plaster casts for setting broken bones, innovated an osteoplastic method for amputation, and introduced anesthesia into field surgery. He developed the “Pirogov Amputation”, a comparatively conservative approach that achieved “an infinitely better functional result”, and increased survival rates. The additional innovation of the plaster cast, first used successfully in the Sevastopol campaign, also increased recovery rates.6

Other reformations headed by Pirogov included a five-tier triage system and the eventual formation of the Khretovozvizhenska; an organized corp of female nurses that increased medical manpower in battle, instituted by an order by the Grand Princess Yelena Pavlovna. The mobilization of female nurses increased troop morale and manpower on the field, helping to improve physical and psychological health of the armies.7

This narrative allows for a simple comparison of the medical evolution on both sides of the war. On the technological front, strong advocacy in Russia by Pirogov for the use of anaesthesia in virtually every operation is contrasted against the British conservative attitude towards its use. Pirogov brought his experience and research in anesthesia to the field, but the British doctors were concerned about the reported haemorrhagic effects of ether, caused primarily by its crude and inaccurate administration. However, the dire need for medical assistance in the field prompted the innovation of field hospitals in both nations.

It must be noted that while the British nurses were paid, the Russians were volunteers, underlining differences in motivation. The British nurses were paid a competitive wage twice that of London and were motivated largely by money, but the Russians were volunteers who “served largely from motives of patriotism and self-sacrifice.”8 While sides were undoubtedly effective and motivated, the professional nature of the British nurses meant that many would continue as nurses after the war, in contrast to the Russian ones who returned to their homes. This in turn prevented Russia from later building up a core of dedicated nurses.9

With regards to increasing the workforce by bringing in female nurses, the Russian administration had a far more receptive attitude to reforms than the British. This was due to Pirogov’s status as a noteworthy doctor and academician according him a degree of authority. His collaboration with the Grand Princess helped bring speedy reforms of the medical system. By contrast, the British administration faced much infighting, most notably between the Nightingale and the military doctors, as well as between the Sanitary Commission and the Army Medical Department, the latter which resented the intrusion of the former over its territory.10

Both sides faced severe logistic problems. The Russian system was marked by corruption, overloaded with four different departments, and also faced geographical constraints in providing supplies. Hinton (2015) noted that the road through Simferopol was the only source of supplies, which was further affected by the military policy of keeping the bulk of provisions away from the front lines. The British system was also faced by severe supply shortages, its ships such as the Prince being sunk, as well as by the failure of the Army Medical Services to provide important supplies such as chloroform or rations with Vitamin C to avoid scurvy.

All in all, the Crimean war caused needless bloodshed, but also facilitated medical innovations that revolutionized medical practice. Perhaps more than just divided over ideological differences, doctors on both sides of the war were united by the common goal of improving medicine itself.

References

- Robert B. Edgerton, 1999. Death or glory: the legacy of the Crimean War. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- M. M. Manring, Alan Hawk, Jason H. Calhoun, Romney C. Andersen, 2009, Treatment of War Wounds: A Historical Review, ClinOrthopRelat Res. 2009 August; 467(8): 2168–2191. Published online 2009 February 14. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0738-5

- Adam Lambert, 2011, The Crimean War. Accessed British Broadcasting Corporation, Accessed 30 January 2016, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/crimea_01.shtml

- Duberly FI. Journal kept during the Russian war: from the departure of the army from England in April 1854, to the fall of Sebastopol. London: Elibron Classics; 2000. First published 1856 by Longman.

- Mike Hinton, 2015,Reporting the Crimean War: Misinformation and Misinterpretation. 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century. 2015(20). DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.711

- “Treating of fractures with plaster first started in Crimea,” Crimealibre, accessed 31 March 2016, http://crimealibre.com/treating-of-fractures-with-plaster-first-started-in-crimea/

- John Pearn, 2005, DOCTORS AND NURSES IN THE CRIMEAN WAR, AMAQ Clinical and Scientific Conference St Petersburg, Russia, accessed 31 March 2016, http://www.clandonaldqld.org/Speeches/Prof.%20John%20Pearn’s%20Address%20Clan%20Donald%20Dinner%202006.pdf )

- Curtiss, J. S..(1966),Russian Sisters of Mercy in the Crimea, 1854-1855. Slavic Review, 25(1), 84–100. http://doi.org/10.2307/2492652

- Yuri Bessonov, Russian Nurses after the Crimean War, Journal of Nursing, Accessed 31 March 2016, http://rnjournal.com/journal-of-nursing/russian-nurses-after-the-crimean-war

- Lynn McDonald. (2014). Florence Nightingale, statistics and the Crimean War,HISTORY OF STATISTICS,http://www.gresham.ac.uk/sites/default/files/30oct14historyofstatistics_florencenightingale.docx.

DYLAN CHAN KAI DER is a student currently serving his National Service as a member of the Singapore Armed Forces. He recently graduated from Anglo-Chinese School (Independent) with an International Baccalaureate Diploma.

ISABELLA NUBARI is a Tan Chin Tuan Scholar, and currently works as a professional speech and debate coach. She recently graduated from Hwa Chong Institution and was awarded a Diploma with Distinction.

Leave a Reply