“Grandgousier was a jolly good fellow in his day, liking to drink as well as any man in his time, and he was very fond of salty food. . . . When he was of manly age, he was married to Gargamelle, daughter of the King of the Butterflies, a pretty wench with a good mug on her. And these two often played the beast-with-two-backs, rubbing their bacons together hilariously, and doing it so often that she became pregnant with a fine son and carried him to the eleventh month.

Then Gargamelle commenced to feel bad down below . . . so Grandgousier rose from the grass and began to comfort her . . . “Only have the courage of a sheep” he said to her, “get rid of this one, and we’ll soon make another.”

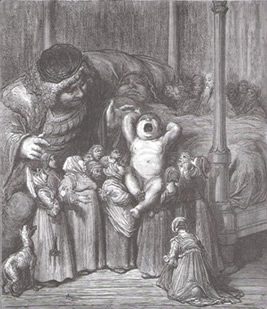

A short while afterward, she commenced to breathe hard and to moan and to cry. Immediately, a lot of midwives came running up from all sides. Feeling her down below, they found some filthy membranes that smelled very bad, and they thought that this was the child; but it was only her bottom dropping out, due to the relaxing of the right intestine, the one you call the rump-gut, all as a result of the tripe she had eaten. . . . Then the cotyledons of her matrix were relaxed, and the infant, leaping up, entered the hollow vein and climbed over the diaphragm to her shoulders (where the said vein divides into two parts) and there he took the left hand path and came out by the left ear . . .”

Freely abridged from the first book of Gargantua by François Rabelais

Much of how Rabelais describes Gargamelle’s pregnancy is by the standard of our times indelicate or indecent. For Rabelais, like Chaucer, as Virginia Woolf put it, “could write frankly where we must either say nothing or say it slyly.” Accordingly, the writing is “improper,” for “a certain kind of humor depends on being able to speak without self consciousness of the parts and functions of the body.”

Leave a Reply