“Were I of Caesar’s Religion, I should be of his desires, and wish rather to go off at one blow, than to be sawed in pieces by the grating torture of a disease. Men that look no further than their outsides, think health an appurtenance unto life, and quarrel with their constitutions for being sick; but I, that have examined the parts of man, and know upon what tender filaments that fabrick hangs, do wonder that we are not always so; and, considering the thousand doors that lead to death, do thank my God that we can die but once.”

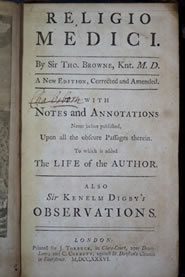

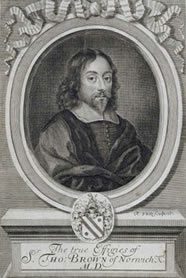

Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682) studied the classics in his youth, then attended the medical schools at Montpellier and Padua, and obtained a medical degree at Leyden. In 1633 he settled in Norwich and became a family doctor. It has been said his fame as a writer overshadowed his work as a medical practitioner. He wrote his first and most celebrated book, Religio Medici in 1636, not for publication but for his own pleasure. When a pirated copy of his manuscript was published in 1642, it quickly became one of the most widely read books of his time, and has remained one of the most foremost classical writings of the English language.

As a young medical practitioner in Norwich he seems to have been averse to sexual intimacy, wishing (in Religio Medici) that we could procreate like trees, without conjunction, and “without this trivial and vulgar way of union . . . the foolishest act a wise man commits all his life.” Later he had second thoughts and fathered 12 children.

He was a great favorite of Sir William Osler’s, who ranked him among “the great saints of humanity” and always kept his book by his bedside. Some of his best prose may be found in the last chapter of Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial, or a Discourse of the Sepulchral Urns lately found in Norfolk, in which he writes that “there is nothing strictly immortal but immortality,” that “there is no antidote against the opium of time,” that most of us must be content to be as though we had not been, to be found in the Register of God, not in the record of man.” A literary critic has compared “the magnificent discourse of the Hydriotaphia” with a symphony of Beethoven “. . . with its vast undulations of rhythmic sound, its triumphal processions, its funeral pageants, its abysmal plunges into unfathomable depths, its ecstatic soarings to the heights of heaven.” But medical diagnosticians reading the Religio Medici may prefer his adage, “Look not for whales in the Euxine Sea”—because there are none!—meaning that common conditions occur commonly and one should be cautious in making diagnoses of rare or exotic diseases.

“I could be content that we might procreate like trees, without conjunction, or that there were any way to perpetuate the world without this trivial and vulgar way of coition: it is the foolishest act a wise man commits in all his life, nor is there anything that will more deject his cooled imagination, when he shall consider what an odd and unworthy piece of folly he hath committed.”

Leave a Reply