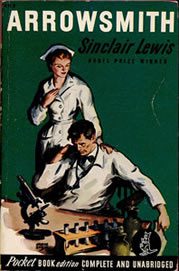

Sally Metzler

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Does art belong in a doctor’s office? According to Sinclair Lewis, a resounding Yes!—so long as the art hangs on antiseptic white walls. In his 1925 novel Arrowsmith, Lewis described the ideal medical reception room—a combination of two warring schools of thought, the Tapestry and the Antiseptic. His father was a country doctor, and Lewis himself briefly toyed with the idea of pursuing a medical career. But he poured his passion for medicine into the pen rather than stethoscope, creating the memorable character Dr. Martin Arrowsmith from the fictive Midwestern state of Winnemac. Lewis entertains and engages the reader by narrating Arrowsmith’s travails of study, practice, and heavy-handed idealism in pre- and post-World War I medicine.

Often stubborn and pig-headed, Arrowsmith nevertheless captures the hearts of his readers with his social naiveté and tunnel-vision pursuits in bacteriology. Despite the best of intentions, especially in his fight against the epidemics so virulent in the early twentieth century, Arrowsmith manages to insult the dairy farmers, the mayor, several heads of famous scientific institutes, and along the way two wives and a few long-lost friends. Nonetheless, Lewis clearly has a soft spot for his misanthropic young doctor. Just as the reader loses all hope in Arrowsmith’s decades of arduous scientific experimentation, the young doctor discovers a phage to wipe out the bubonic plague sweeping across the island of St. Martin. After years of non-acceptance by the elite of the medical profession, Arrowsmith is anointed a savior by all and elected into the temple of medical fame.

In his early days as a medical student, Arrowsmith encounters several colorful medical characters, among them a Dr. Roscoe Geake of the New Idea Medical Instrument Company. Though always loathe to attend lectures that would steal him away from study, he grudgingly received the wisdom of Geake who spoke on the Art and Science of Furnishing the Doctor’s Office:

Nothing is more important in inspiring [the patient] than to have such an office that as soon as he steps into it, you have begun to sell him the idea of being properly cured. I don’t care whether a doctor has studied in Germany, Munich, Baltimore, and Rochester. I don’t care whether he has all science at his fingertips, whether he can instantly diagnose with a considerable degree of accuracy the most obscure ailment . . . If he has a dirty old office, with hand-me-down chairs and a lot of second-hand magazines, then the patient isn’t going to have confidence in him; he is going to resist the treatment—and the doctor is going to have difficulty in putting over and collecting an adequate fee.

To go far below the surface of this matter into the fundamental philosophy and esthetics of office-furnishing for the doctor, there are today two warring schools, the Tapestry School and the Aseptic School, if I may venture to so denominate and conveniently distinguish them. Both of them have their merits. The Tapestry School claims that luxurious chairs for waiting patients, handsome hand-painted pictures, a bookcase jammed with the world’s best literature in expensively bound sets, together with cut-glass vases and potted palms, produce an impression of that opulence which can come only from sheer ability and knowledge. The Aseptic School, on the other hand, maintains that what the patient wants is that appearance of scrupulous hygiene which can be produced only by furnishing the outer waiting-room as well as the inner offices in white-painted chairs and tables, with merely a Japanese print against a gray wall.

But, gentlemen, it seems obvious to me, so obvious that I wonder it has not been brought out before, that the ideal reception-room is a combination of these two schools! Have your potted palms and handsome pictures—to the practical physician they are as necessary a part of his working equipment as a sterilizer or a Baumanometer. But so far as possible have everything in sanitary-looking white—and think of the color-schemes you can evolve, or the good wife for you, if she be one blessed with artistic tastes! Rich golden or red cushions, in a Morris chair enameled the purest white! A floor-covering of white enamel, with just a border of delicate rose! Recent and unspotted numbers of expensive magazines, with art covers, lying on a white table! Gentlemen, there is the idea of imaginative salesmanship which I wish to leave with you.

Sinclair Lewis, Arrowsmith

SALLY METZLER received her PhD in Art History from Princeton University. Currently, she is Guest Curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Spring 2013 – Volume 5, Issue 2

Leave a Reply