Gregory Rutecki

Cleveland, Ohio, United States

|

|

|

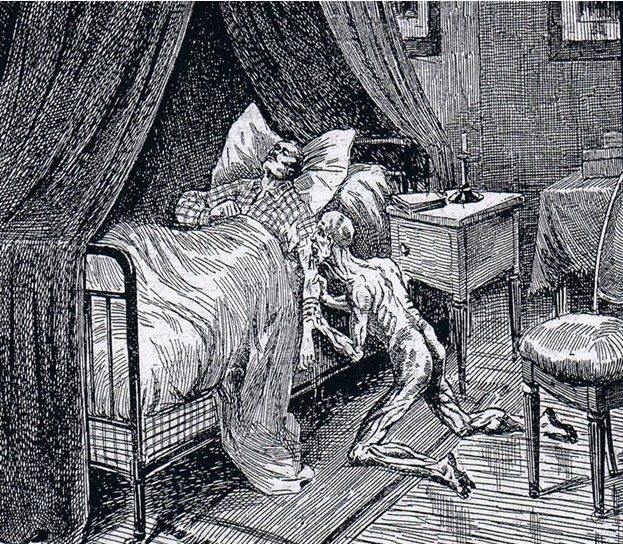

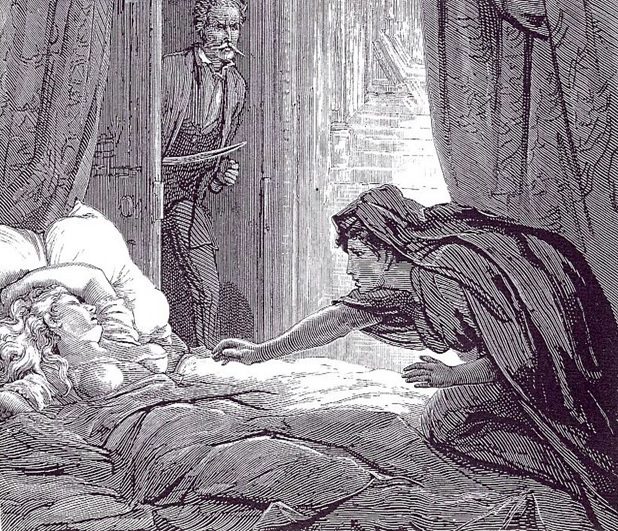

| Illustrations of vampires. Provided by author. | ||

“In New England . . . It is believed that consumption is not a physical but a spiritual disease . . . as long as the body of a dead consumptive relative has blood in its heart it is proof that an occult influence . . . is . . . draining the blood of the living into the heart of the dead and causing (a relative’s) rapid decline.”1 – New England Anthropologist George Stetson, 1896.

Our most ancient ancestors were forced to confront what was for them the most unfathomable of all tragedies—disease and death. As Tennyson declared in laureate’s meter:

“Every heart this May morning in joyance is beating . . . Yet all things must die . . . The heart will cease to beat . . . in the dark we must lie . . . The red cheek paling . . . ice with warm blood mixing . . . all things must die.”

Without the aid of science, primitive humanity naively processed suffering and finitude. Their lives were Hobbesian: nasty, brutish, and short, so “lacking a proper grounding in physiology, pathology, and immunology, how are people to explain disease and death?”2 The bacterial and metabolic dynamics of bodily decomposition were also unknown to the ancients. Vigorous postmortembacterial metabolism—literally forcing bloodstained secretions out of the mouths of those exhumed—would be misunderstood as signs of ineffable resuscitations. The presence of blood in the stilled heart would be similarly interpreted. During epidemics preceding the germ theory, as one family member after another redundantly succumbed to diseases such as tuberculosis—growing ever and ever paler as those who died before—the myth of the dead returning for living blood was embraced. Vampires entered human history millennia long before Bram Stoker’s Dracula and reflected a universal, pre-scientific, and Promethean struggle against the most hated of humankind’s enemies—disease and death:

“The vampire forms part of the misunderstood history of humanity. He possess a role and a function—he did not just spring from nothingness in the 17th or 18th century. He fits within a complex set of representations of life and death that has survived into the present.”3

Contemporary depictions of vampires are surfeit with erotic beings, inhabiting glamorous existences at the expense of another’s blood. These caricatures—as portrayed by Dracula, Nosferatu, and the Twilight Saga—trivialize a critical and universal chapter in human history. The authentic vampire appeared when pre-scientific humans were compelled to consider illness, death, and decomposition.

The vampire myth: shared universally from antiquity to the nineteenth century

“Peter Plogojowitz . . . died . . . and had been buried . . . within a week, nine people, both old and young, died also . . . while they were yet alive . . . Plogojowitz . . . (came) to them in their sleep, laid himself on them . . . so that they would give up the ghost. . . . They exhumed . . . (his) body . . . which was completely fresh . . . hair . . . nails . . . had grown on him; the old skin . . . had peeled . . . a fresh new one had emerged under it . . . I saw some fresh blood in his mouth . . . he had sucked from the people killed by him . . . (we) sharpened a stake . . . as he was pierced . . . much blood, completely fresh, flowed . . . through his . . . mouth.” (1725)2

Tuberculosis was a disease of antiquity with a unique nom de guerre—consumption— and helped give impetus to the vampire myth. The ancient and universal presence of “bloodsuckers” will be chronicled from early times of recorded human existence.

In Western culture, ancient Greeks called their mythological bloodsuckers Lamia.4 The Libyan princess Lamia had an illicit love affair with Zeus. Hera, the wife whom Zeus spurned, killed all of Lamia’s children and drove Lamia into exile. The tale—told by Aristophanes (446–386 B.C.E.) and Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.)—described how Lamia sought revenge by sucking the lifeblood of babies. In the second century B.C.E., a manuscript fragment by Titinus suggested garlic hung around the neck of children would protect them from Lamia.3 After the arrival of Christianity, undead demons were accommodated by the new religion and were renamed Vrykolakas, roaming undead beings afflicting humanity.4 Many cultures followed with Albanians, Montenegrins, Bulgarians, Croatians, Hungarians, Serbians, and Russians naming their ethnic vampires.4 In fact, it was the Walachian prince, Vlad Tepes (the Impaler), (1431–1476), who was Bram Stoker’s model for Dracula. The German schrattl or shroud eater was thought to rise from the grave spreading disease.4 The presence of mythic undead creatures populated Native North and South American cultures.4 In the 13th and 14th centuries undead Icelandic beings were added to other myths and called Grettirs.2

Although it has been opined that “East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet,” the vampire myth brought cultural extremes together. Chinese jiangshi were corpses of those drowned, hung, or victims of suicide returning to drain humans of their life force. The Japanese and culture of India described similar undead blood suckers.4 As fatal communicable diseases and death were universal—and otherwise inexplicable—so were naïve myths of vampires. Myths would evolve into metaphors as well.

Prescientific cultures: mysteries of decomposition

“ . . . the body swells . . . Discoloured natural fluids and liquefied tissues are made frothy by gas and some exude from the natural orifices, forced out by the increasing pressure in the body cavities . . . eyes bulge . . . little wonder that Bacon was convinced that purposeful dynamic spirits wrought this awful change.”2

“Blood migrates . . . in the course of decomposition . . . the gases in the abdomen increase in pressure . . . and are forced upwards and decomposing blood escapes from the mouth and nostrils.”2

In 1739, Austrians occupying Serbia and Walachia investigated reports of a gruesome local custom: Exhuming dead bodies and re-killing them.2 The practice was a consequence of their ignorance of natural processes of bodily decomposition. During decomposition intestinal bacterial gas flows through blood vessels and tissues pushing blood stained fluids through the nose and mouth.5 Seven days after death, cadaveric skin loosens, the top layer sheds off in sheets in a process called skin slippage.5 At a 1732 exhumation it was written,2 “They dug up Arnod Paole forty days after his death . . . and they found . . . fresh blood had flowed from his eyes, nose, mouth and ears; that the shirt (was) completely bloody . . . the skin, had fallen off . . . he was a true vampire, they drove a stake through his heart.” The presence of blood after death was interpreted as a sign of reanimated life—albeit at someone else’s expense. In the context of consumption, the visible confluence of paleness and hemoptysis lent credence to postmortem appearances suggesting life after death. That perception would be further fueled by ignorance regarding the transmission of infectious diseases.

Prescientific cultures: communicable diseases prior to the germ theory

“The Vampire is consumption in human form, embodying an evil that slowly and secretly drains the life from its victims.”2

“For as long as what caused tuberculosis was not understood . . . tuberculosis was thought to be an insidious, implacable theft of a life . . . Any disease that is treated as a mystery and acute enough to be feared will be felt to be morally . . . contagious.”6

– Susan Sontag

Prior to the Germ Theory, from the time of Aristotle, miasmas—or currents of contaminated air circulated by winds—were considered the cause of communicable diseases.7 As a result, continued connections between consumption and the vampire myth persisted into the late Nineteenth Century.

“Mercy died, apparently of tuberculosis, in January 1892 . . . Mercy was a vampire . . . Mercy’s brother Edwin was a strapping young man of 18 . . . in 1891 Mercy and Edwin both became ill . . . the boy went off to Colorado, where he recovered. His sister (Mercy) eventually was carried to her grave by the illness . . . Edwin returned still in weak health . . . why was such a strong man’s life draining away? Why had the same thing happened to Mercy only a few months before . . . nothing less terrible than a vampire was sucking their children’s blood and taking their lives with it . . . to their infinite horror, Mercy’s body, which had blood and seemed unnaturally preserved, with color still in the cheeks . . . (They) removed the corpse’s heart and burned it on a rock.”1

Consumption—the captain of all these men of death—was chosen and persisted as a metaphor for vampirism. Charles Dickens wrote, that for individuals with tuberculosis, “life and death are so strangely blended” that death takes the “glow and hue of life, and life the gaunt and grisly form of death” (Nicholas Nickleby). Dickens and others who witnessed victims of consumption—precariously hovering between life and death—recognized the stigma:

“The emaciated figure strikes one with terror; the forehead covered with drops of sweat; the cheeks painted with a livid crimson, the eyes sunk; the little fat that raised them in their orbits entirely wasted; the pulse quick and tremulous; the nails long, bending over the ends of the fingers; the palms of the hands dry and painfully hot to the touch; the breath offensive, quick and laborious, and the cough so incessant as scarce to allow the wretched sufferer time to tell his complaints.”8

Science, ascendant in the late nineteenth, early twentieth century, identified Mycobacterium tuberculosis as the agent of tuberculosis. Science also shed light on bodily decomposition after death. The cure of tuberculosis would follow and the myth and metaphors surrounding tuberculosis would disappear. However, despite science, for Susan Sonntag, other diseases—such as cancer and AIDS—would resuscitate illness metaphors.

The contemporary vampire craze does not do justice the authentic history of the vampire. As healthcare professionals, it is critical to understand humanity’s millennially long struggle to place illness and death into a plausible perspective. This effort is an essential part of medicine qua humanism. As Tennyson also said, from his personal theistic worldview perspective, “Thou madest man, he knows not why, he thinks he was not made to die.”

References

- Bell ME. Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires. Wesleyan University Press, Connecticut, 2001, pages 50, 236, 7-12.

- Barber P. Vampires, Burial, and Death. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1988, pages 3, 5-7, 85, 103, 115, 15-17,

- Lecouteux C. The Secret History of Vampires: Their Multiple Forms and Hidden Purposes. Inner Traditions, Rochester, Vermont, Toronto. 2010, pages 5-6, 15, 99-100.

- Sherman, A. Vampires: The Myths, Legends, and Lore. Adams Media, Avon, Massachusetts, 2014, pages 42, 45-6, 47, 60, 71-82.

- Iserson KV. Death to Dust: What Happens to Dead Bodies? Galen Press Ltd., Tucson, 1994. Pages 41-43.

- Sontag S. Illness as Metaphor. The New York Review of Books, January 26, 1978, read online, Dec. 10th, 2016.

- McMahon D. and Rutecki G.W. “In anticipation of the Germ Theory of Disease: Middleton Goldsmith & the History of Bromine.” Pharos 2011;74:4-12.

- Dubos R. & Dubos J. The White Plague: Tuberculosis, Man, and Society. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 1952. Page 118.

GREGORY W. RUTECKI, MD, received his Medical Degree cum laude from the University of Illinois, Chicago (1974). He completed Internal Medicine training at the Ohio State University Medical Center (1977) and a Fellow-ship in Nephrology at the University of Minnesota (1980). After 12 years of Private Nephrology Practice, he re-entered Academic Medicine at The Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine (awarded “Master Teacher” designation) and became the E. Stephen Kurtides Chair of Medical Education at Evanston Northwestern Healthcare and Professor of Medicine at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. He now practices Medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Spring 2017 – Volume 9, Issue 2

Leave a Reply