Michael Meguid

Syracuse, New York, United States

|

I saw two bright colored polaroids: One pictured Rudolph, a burly coal miner with a white bandage about his left ankle. The second was a close-up showing a four-inch long festering ulcer overlying his Achilles tendon. Its crater floor appeared necrotic, slimy, and green. The margins looked chronically inflamed and rolled inwards. The lower edge was thicker and suspicious of an early squamous cell cancer—a classic Marjolin’s ulcer. As an oncology surgeon, I had only seen a similar photo in a textbook. I was certain of the diagnosis, although I had never treated one.

Tom and Dorothea, my next-door neighbors, casually showed me the photos during a gathering of distraught parents with teenagers approaching driving age. They congregated at our home on a gray Saturday afternoon, November 25, 1990, to petition our town of Manlius, a Syracuse community, for a traffic light at the top of our street. Another sixteen year old had died in a crash at its intersection on Thanksgiving.

“Is this something you could operate on?” asked Tom.

“Yes,” I said assuredly, as if answering an academic question. “Where did you get the photos? And who is the person?”

Tom and Dorothea had visited Poland the previous summer, accompanied by Rudolph’s nephew, Jan, one of Tom’s students at Utica College in Upstate New York. Their visit coincided with the tumultuous sociopolitical upheaval. The anti-communist Solidarity movement, the Soviet-bloc’s first independent trade union, ended communist rule and saw its co-founder, labor activist Lech Walesa, form the nascent Solidarity government. Accompanied by Jan, the American couple traveled to Jaworzno, an industrial city of about 90,000, south of Warsaw in the Silesian Highlands where they met Rudolph. Jan had asked them if his uncle could be cured in America.

Tom continued, “One morning in 1965, Rudolph was riding his old motor cycle to the mine. Bumping over railroad tracks it overturned, pinning his left leg beneath him. The battery’s acid spilled onto his ankle, burning his skin, eating it away and creating a painful ulcer.” During the first few years his frequent wading in polluted water during his twelve-hour mining shifts constantly irritated it, preventing the wound from healing. When his political activity as a Solidarity union leader elevated him to a desk job at the mine, he had access to the best medical care Poland could offer—the ulcer still did not heal. Why had all the salves, creams, and medical attention not healed it? The situation could be more complicated than I understood.

“Would you be willing to operate on Rudolph if we brought him to Syracuse?”

“Sure,” I replied.

After the neighborhood meeting I was haunted by the commitment that I made. I had agreed to operate on a patient based solely on a polaroid picture of a long-standing non-healing ulcer. Did I have all the facts? How old was he? Was he a diabetic, did he have peripheral vascular disease, or hypertension? Had I made a rush to judgment, an imprudent error, by readily agreeing to help a patient, sight unseen? What surgeon would have made a decision to operate based on a photo and a vague history of spilled battery acid?

That night my anxiety and self-doubts resurfaced. I had not been brave or bold but foolhardy. My biggest fear was that Rudolph would travel 4,000 miles just to discover I could not help him. I took solace in thinking that as a miner from a communist country he probably would not get a visa to the US because of a politically sensitive time in US-Polish-Soviet relations. The odds were the issue would somehow blow over without my involvement.

Unknown to me, by nonchalantly offering to operate, I had set into motion a sequence of events spearheaded by Tom and Dorothea. Based on the assurance of my photo diagnosis, in the weeks that followed they had mobilized and rallied the generous Polish, Irish and Catholic communities, as well as family and friends, to raise the necessary cash. They convinced the local pharmacy to provide free supplies, while a home health agency had agreed to assist with post-operative care—gratis. Tom had called in his chips and had persuaded a contact in the State Department to issue Rudolph a visa.

Three weeks after the neighborhood meeting, Tom called me wanting to know when I would like Rudolph to arrive.

“Arrive?”

I was amazed to discover the progress he and Dorothea had made to persuade various disparate groups to help a relative stranger and their determination to make Rudolph’s visit a reality. Now the ball was in my court. Tom’s call stirred me to action. I urgently made my rounds seeking tentative pledges from a variety of colleagues whose specialties I would need to assist me in operating and caring for Rudolph. I started by approaching medical colleagues who were first generation Americans or immigrants like me, likely to be sympathetic to a foreigner’s plight, although I had found America to be a generous country.

I asked an American burn surgeon to obtain a skin graft to cover the defect left by the excised ulcer. I recruited a Czech internist with residual Russian language skills to clear Rudolph pre-operatively, a Lebanese urologist to ensure Rudolph did not have an enlarged prostate that could lead to post-operative urinary retention, and an Italian anesthetist with charm and compassion to put Rudolph to sleep. To confirm the finding of cancer, I sought the help of a French pathologist.

I impressed on them the need for free services with minimum laboratory expenses. I would like to think that they were mildly amused at my commitment to operate based on a photograph. All agreed to help.

When Rudolph stood at my front door shortly after Christmas, he looked older than 49 years. At 6’ 6”, broad shouldered and strong with a rugged miner’s physique, he towered over me. His big calloused hands engulfed and nearly crushed my outstretched surgeon’s hand. His handshake shook my body, pulling me off balance. His dark, intense eyes transfixed me, while his mustache-draped smile and gentle melodious voice conveyed greetings and gratitude in Polish. Although he spoke no English, I was captivated.

As he lay down on Tom and Dorothea’s couch, kicking off his boots, and yanking up his pant leg, my apprehensions slowly ebbed as I cut through the gauze wrapped around his ankle and remove the stained dressing. Yes, it was the ulcer on the polaroid. In the fading light of the post-Christmas afternoon, I saw it clearly. It was round and the size of a baseball, weeping, the lower edge confirming my suspicion that it had transformed into an early cancer from twenty-five years of chronic irritation. My concerns did not completely disappear until after my examination showed that it was not tethered to the underlying bone, a neighboring major artery, or the tendon. He did not have enlarged lymph nodes in his left groin to suggest that the cancer had spread.

Dorothea, the valiant soul, chauffeured us around from one office to another throughout late December’s driving snowstorms to meet my colleagues. Rudolph’s massive form, his congeniality, grace, and charisma minimized the obstacle of the language barrier. I had recruited the Reverend Alfred Babel, or Father Al as we affectionately called the Polish-speaking hospital Catholic chaplain, to accompany us. He informed Rudolph of each doctor’s plans. Father Al conveyed the concerns of this amiable and often bewildered man, while his translated explanations and reassurances seemed to assuage Rudolph’s mounting and understandable fears. All who examined him concluded that he was healthy—a good operative risk.

To keep things under the administrative radar in the hope of minimizing cost, I scheduled the operation for January 1, 1991. It was a post-snowstorm sunny day—surely a good omen. All was set. Taking leave in Russian of the internist in the preparation room, the anesthetist, the chaplain, a nurse, and I rolled a jovial but nervous Rudolph on a gurney toward the operating room. Jovial—for twenty-five years of misery was about to end. Father Al stopped abruptly outside the door. “I faint at the sight of blood.”

Rudolph, in delicate mid-air transfer between gurney and operating table, sensed the impending loss of his translator and compatriot. Disregarding the loss of decorum caused by his exposed bottom, and the rush of the nurses trying to cover him, he raised himself off the table, yelling in Polish and gesturing in agitation and fear.

Chaos and confusion reigned in the hallowed temple of surgical order. For a moment, it seemed that he would change his mind about having the operation. We finally understood that he wanted Father Al’s presence, and that he did not want to be “put to sleep.”

Italian professionalism resolved the issues. A spinal anesthetic numbed Rudolph from the waist down. Father Al sat next to Rudolph and held his hand, comforting him in murmured Polish exchanges, and to block their view of the operative field, an unusually high drape was raised. Rudolph was too tall for the table, so that his operative leg hung off the end. A team of resourceful nurses added an extension board solving this minor obstacle.

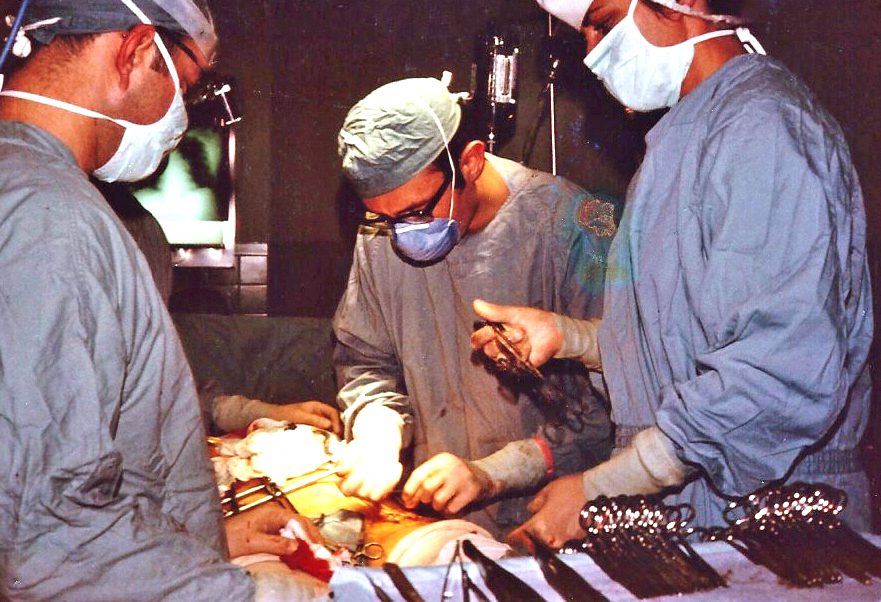

Tranquility restored, I washed the leg and painted it from groin to mid-foot with antiseptic solution, and the operation began with the harvesting of donor skin from Rudolph’s thigh by the burn surgeon. I excised the ulcer, careful to preserve the underlying nerve to the foot, as well as the major artery and vein. Bleeding points were coagulated while the margins and deep surface of the excised tissue were marked with Indian ink to orient the specimen in case I needed to remove more tissue should a cancer be found. I handed the specimen to the waiting pathologist with a “Bon chance,” and turned my attention to the left groin and began dissecting the superficial lymph nodes, for these too were examined immediately, and if cancer free, the necessity of doing a deeper node dissection would not be indicated. The pathologist found two nests of squamous cancer cells in the ulcer’s lower margin. They looked very much like clusters of dark menacing pearls, confirming my clinical suspicion. I had completely excised the cancer. The nodes were without cancer.

Elated, I popped my head around the drape to share the good news with Rudolph. He was fast asleep. A sense of quiet accomplishment settled in the room as we completed the skin graft, dressed the wound, and immobilized the ankle with a cast, accompanied by the hum of an Italian aria from the anesthetic end of the table.

Rudolph remained under my hospital care for four days. Ninety-five percent of the new skin had grafted. He returned to the warmth and hospitality of Tom and Dorothea’s family to recuperate. No matter how late I returned from the hospital, I visited Rudolph daily. I cleaned and attended to the wound by stripping off dead tissue to ensure that the skin graft remained healthy and redressed it with the generous supplies provided by our local pharmacist.

Rudolf’s spirits rose with the operation’s success and return of mobility to his ankle. He eagerly shared photos of his family with charm and good humor, but he had not learned much English, apart from “thank you.” In my tired state after a day’s surgery, I was a poor student, picking up no Polish.

As spring approached and his wound became well healed, Rudolph became restless. Cured, he yearned for his family. He left Syracuse on March 17, gracious, smiling and hugging me. We had accomplished our task.

This giant of a man, amiable, and trusting, and I had developed a special connection. I never told him that my German grandparents were born in the pre-war German Schlesien—now the post-war Polish Silesian Highlands. We probably belonged to the same family.

Last Easter, I received a card. Rudolph wrote in English the two words he had learned and included a wafer from an Easter service. To me it had more than a religious meaning. I thought back on all the people and organizations, above all Tom and Dorothea, who had helped make his cure a reality. The wafer represented the generosity of our human spirit and the willingness of a community to work together across national and cultural boundaries to achieve a common goal.

MICHAEL MARWAN MEGUID was born in Egypt and spent his childhood in Germany and England, where he attended University College Hospital Medical School, London, followed by surgical residency at Harvard Medical School. As a surgeon/scientist in oncology and clinical nutrition, he earned a PhD in nutrition at MIT. While operating and researching at Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, he authored over 400 scientific papers and founded the International Journal, Nutrition, of which he serves as Editor Emeritus. On retiring, he earned an MFA from Bennington Writers Seminars, VT. He lives and writes on Marco Island, Florida.

Leave a Reply