Mojca Ramšak

Ljubljana, Slovenia

In the center of the Spanish city of Alcalá de Henares, near Madrid, stands an exceptional institution—the Antezana Hospital, officially Hospital de Nuestra Señora de la Misericordia. It is one of the oldest continuously operating hospitals in Western Europe, having functioned for more than five centuries.

Today, it houses a nursing home for up to twenty-three elderly residents, while the historic premises are open to the public as the Museum of Medicine of the Golden Age. The exhibitions cover the history of medicine—from students and professors to treatments, diseases, medicines, prescriptions, and medicinal plants. Visitors can see the old pharmacy, courtyard, hospital kitchen, male and female wards, medicinal plant garden, doctor’s room, the rooms of St. Ignatius of Loyola, and the church. The historic area complements the renovated residence, adapted to current regulations for social care institutions.

The story of the hospital began in 1483, when nobleman Don Luis de Antezana and his wife Doña Isabel de Guzmán bequeathed a large part of their estate to establish a hospice for the sick under the patronage of Our Lady of Mercy. At a time when healthcare was a privilege of the wealthy, the couple demonstrated exceptional charity—their wish was to provide free assistance to the poor, the sick, travelers, and pilgrims. Antezana Hospital was established with twelve beds and with the commitment to always care for at least three patients, with the aim of increasing this number through donations. During periods of economic prosperity, the capacity increased to forty beds. From the beginning, the mission was clear: to provide physical and spiritual assistance to those most in need. Both spouses are buried in the hospital church.

With the establishment of the University of Alcalá de Henares in 1499, Antezana Hospital entered a new era. Hospital doctors and surgeons became university professors of medicine. From 1540 to 1830, students performed anatomical exercises and dissections at Antezana Hospital, placing it among the first university hospitals in Spanish history. In 1573, a nursing unit was established at the hospital, considered a milestone in the professionalization of nursing. This unit continues to operate to this day. Doctors who treated the poor at Antezana drew ideas for medical works, published throughout Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, precisely from this direct clinical experience. Many of these doctors later became court physicians to Spanish kings or chief physicians of Castile.

An essential part of treatment at Antezana Hospital since the sixteenth century has been the pharmacy with its herb garden. The pharmacist’s garden, intended for preparing medicines for patients, was arranged in the inner courtyard. Medicinal plants were cultivated here, which formed the basis for preparing medicines, tinctures, and ointments. The herb garden, indispensable to the hospital pharmacy, is still in use today.

A special chapter in the history of Antezana Hospital is represented by Ignatius of Loyola, who during his studies at the University of Alcalá de Henares (1526–1527) lived in the hospital and worked there as a nurse. In the kitchen, which has been preserved to this day, he prepared food for the sick. The kitchen was used until the mid-twentieth century and served both the hospital and as a dining hall for the poor. Meat, chickpeas, biscuits, wine, and vegetables were everyday food for the poor. It was here that Ignatius first lived together with his companions and followers, which represents the beginning of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), formally founded in 1534 in Rome. After the canonization of St. Ignatius in 1622, his veneration spread widely. Part of the kitchen was converted into a chapel, and later, at the end of the seventeenth century, a Baroque chapel with an impressive dome was built, literally placed within the former room where the saint had resided.

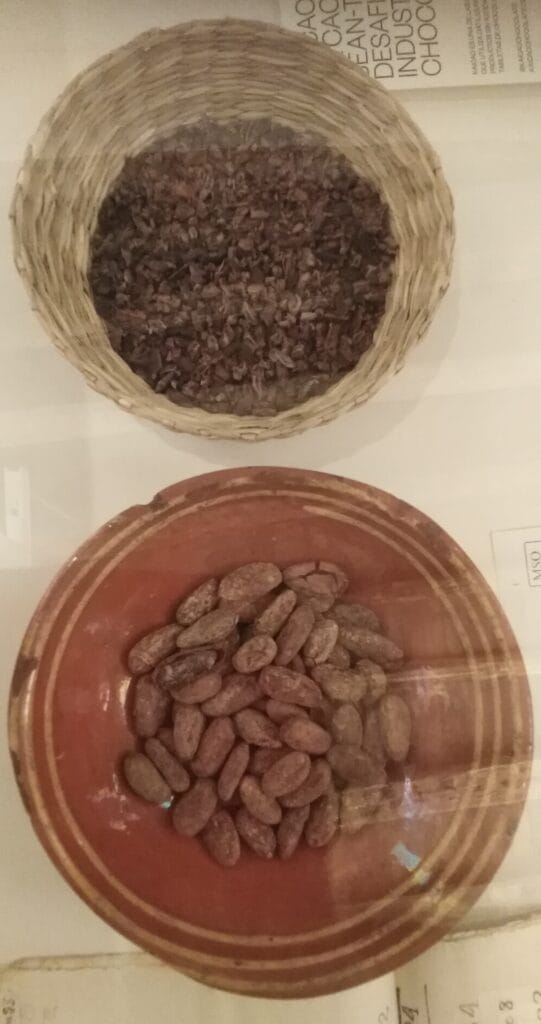

An interesting detail from the history of medicine at Antezana Hospital is the use of chocolate for therapeutic purposes. From the late seventeenth century, there is evidence of the arrival of cocoa at Antezana from Mexico and Caracas, where it was called the food of the gods. By the mid-eighteenth century, this beverage became an essential part of patient care. The foundation’s archive holds a document from the early nineteenth century with the instruction that chocolate should be given to patients in the afternoon, as prescribed by the doctor. The archive also contains extensive documentation on the purchase of cocoa in Venezuela and Mexico and medical instructions regarding its use as part of therapy and nutrition. Chocolate was valued for components such as theobromine (muscle relaxant), caffeine (stimulant), theophylline (vasodilator), lecithin, and antioxidants, as well as for its anti-aging effects on the skin and benefits for the heart. Although chocolate was also a delicacy of the aristocracy, at Antezana, it was given to poor patients treated there.

Antezana Hospital is not merely a monument to the past, but living proof that the history of medicine intertwines with architecture, art, and spiritual heritage, creating a unique entity that still serves its original purpose today—caring for those in need—while simultaneously inspiring new generations of healthcare workers. Today it is run by a brotherhood of nine knights, who continue its tradition of holistic care more than five centuries later.

Written on the occasion of the symposium on the history of medicine Continuity and Change in Southern European and Mediterranean Healthcare (1850–2000), held at the Faculty of Medicine in Alcalá de Henares, Spain, January 14–16, 2026.

MOJCA RAMŠAK, PhD, ethnologist and philosopher, specializes in the history of medicine, medical anthropology, and cultural heritage. She is affiliated with the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. She is the author of eleven scientific monographs and leads an interdisciplinary project titled “Smell and Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Her full bibliography is available here.

Leave a Reply